You know, very, I don’t know what did they do, the things were all over the place. The machine, for example, was ruined, an old stove was taken upstairs, you know, I don’t know how did they carried them, those things. There was a lot of disorder in the building, empty apartments, without anything inside them. They didn’t touch the pictures and some documents because, after all, it was a building.

And one, one resident there, she was Dalmatian, older, she didn’t have anywhere to go, so she stayed there. She told us that they brought the truck at the entry, so we couldn’t see what they took, what are they loading. Cassettes, we had a lot of video cassettes, all with serious music, recorded, different kinds. My husband was fond of classical music, he used to record instrumentals, orchestras, of different kind. We found those in another building. So, unexplained things happened, I don’t know, I don’t know.

But it’s interesting how one remembers everything he had, it happened a few times, people don’t remember everything they have, but if the things are missing… It was a bit funny. I made the list of everything that was missing because I knew what I had in my cabinet. Only notes, notes, my songs and so, I, I threw them behind the cabinet, there was free space but couldn’t go down further, I found them there.

The research on Pristina focuses on culture, history and architecture. These dimensions are explored through personal accounts and tend to offer a pool of multiperspectival narratives, democratizing public discourse and the way local histories are told. By means of digital storytelling we want to bring out the many facets of the city and contribute towards a multilayered understanding of urban and socio-economic developments, starting from the interwar period until today.

Pristina project is part of the “Inter-community Dialogue through Inclusive Cultural Heritage Preservation” project funded by the European Union’s Instrument contributing to Stability and Peace (IcSP) and implemented by United Nation Development Programme (UNDP) in Kosovo.

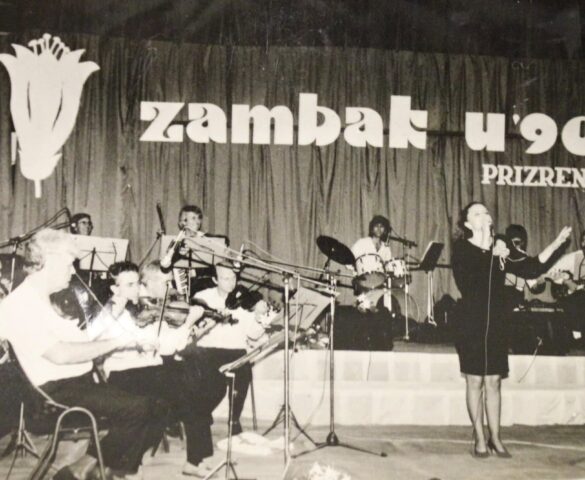

Pranvera Badivuku

ComposerSevim Baki

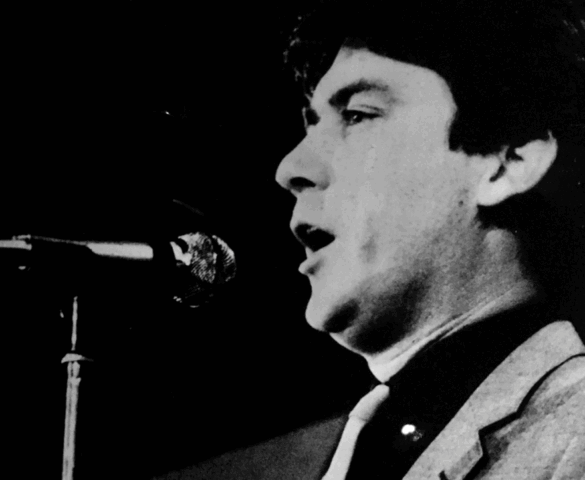

Artist/SingerWhen I was very young, there was a song by Emel Sayın, Sevda sevmessen [When you don’t love, love]… It was called Rüzgar [Wind], I was very young and I used to imitate her very often. When my cousins would come to stay over, I would say, ‘Do you want me to imitate Emel Sayın?’ I would sit down, put the pillows on the floor, my hair on one side {shows with her hands}, I would say, ‘Go get the hairdryer so my hair would look like it’s blown by wind just like hers in the music video.’ They applauded me. When a guest would come to visit us, my father always used to say, ‘Come on, sing some songs.’ Now, when I think about it, I can say that these were the hints that I was going to be connected to music.

Lidia Mirdita Tupeci

AccountantThen the street lights were turned on, and we were like, like, for three months when you are like… When I saw the lights on, I said to my neighbor, ‘Kuku, something bad will happen.’ You know, I said, ‘They turned the lights on…’ I look at korzo and we are talking to one another, ‘Should we go out… let’s meet close to Grand.’ God knows what’s happening. Tomorrow morning, when KFOR troops came from Macedonia, I was looking out from the balcony. Now KFOR came from this side, the road from the hospital, perhaps they did not know the way or they were just too many of them, you know.

It was raining, I remember this. They were swearing, ‘Who invited you here?’ And I heard a Serb saying this, ‘Why are you swearing at them? Do you know who invited them here? Milošević did.’ I witnessed this. Afterwards, it was different. They started running away, you noticed it when your neighbors were not around anymore. They left at night or I don’t know, but they disappeared.

Sonja Artinović

EconomistWe were together, yes, we were spending time together with, with the Turks, that, those who lived there in those houses, who wore special nanule, which I adored, wooden. (laughs) And with their nanule, they entered their hamam, those are gone now. I think they are gone. Well, for example, they did not have parquet, for example, but they had wooden flooring {explains with hand}, the long deck, that they had to brush. It was yellow, like a gold yellow. Very clean people and this Mazlum of mine, who is still here today, you know. […] After so many years of knowing one another, and so much love and evocation of childhood memories, because she knew me as a baby, what kind of people we are, how we were, all that we did. I mean, all our adventures and such, she taught me how to bake lokum, and even katmer pie and a kol pie, she taught me everything. My mom taught them other things, so we exchanged. I say, like a family.”

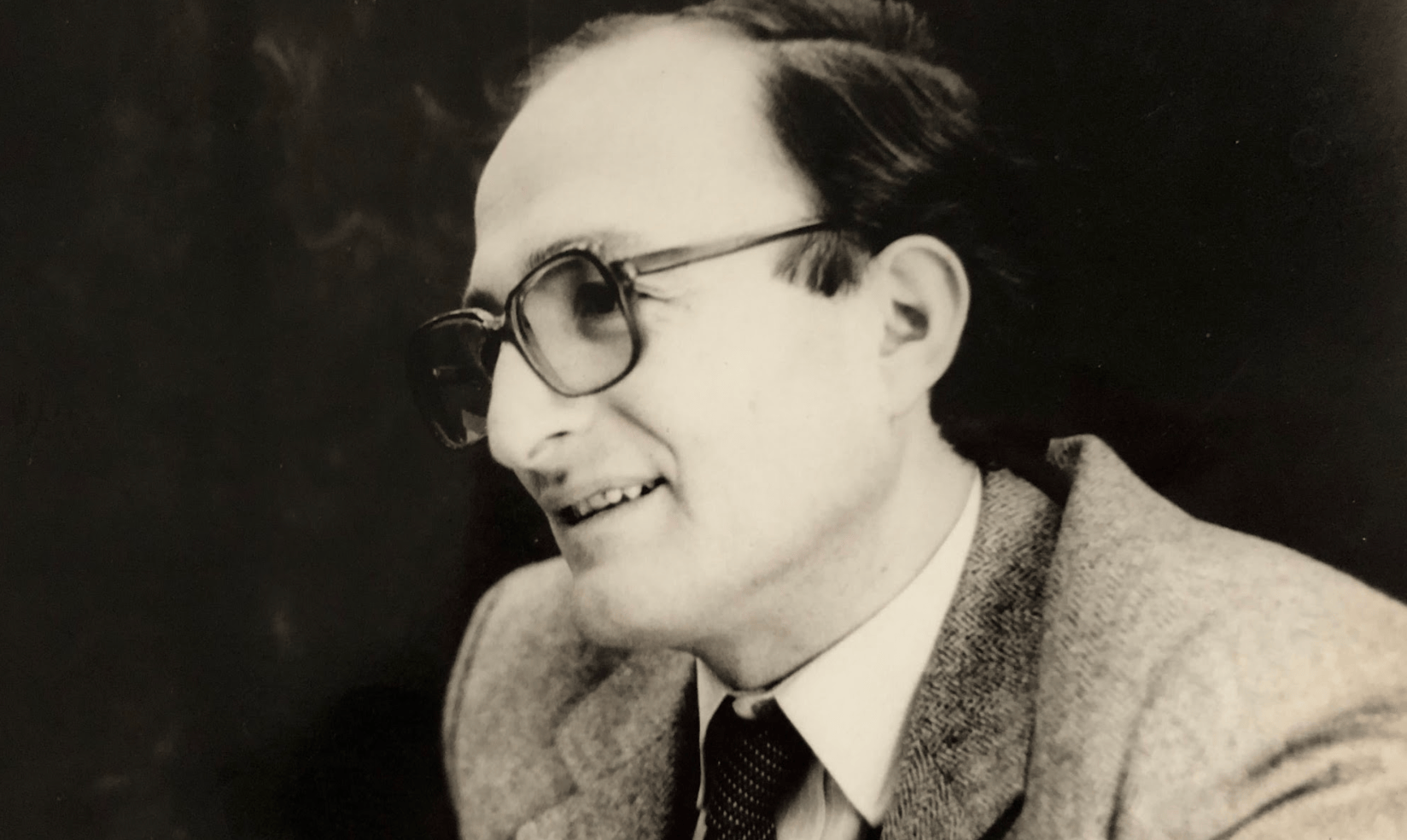

Skender Boshnjaku

NeuropsychiatristOh, that was a great moment, even from, from… it was a Saturday when NATO came, so it was June 12, Saturday… June 11 was Friday, no… Yes, exactly on June 11, Friday, June 11, Saturday. Usually, I didn’t sleep, but from the window of where I lived, you could clearly see the house, and when I saw the tank, it was early. Oh, until this day… now at this moment I have… I felt a lot of happiness, I said, ‘Oh, wife, NATO came. Let’s salute them!’ And I was trying to run until I saw the tank, but when the tank turned, I saw the tank and I put my hands up, and it was miraculous. Something incredible. Yes, even for me, it was incredible that such a crazy atmosphere was created that people forget. For me, that was something unbelievable and…

Momčilo Trajković

Political activistThe new building was inhabited by the old Serbs, old Serbs of Pristina, old Turks and old Albanians. They had houses where the cinema is now, previously Omladina Cinema, do you know that settlement now? And, when those buildings were built, they were, since they were old houses, they gave apartments to host the owners of houses and they all lived in that building. Everyone was settled in that building. I was the only one and another journalist, we were, like this, to say from aside. All the others were… they simply transferred all of their settlement to this building: the old Albanians, the old Serbs, the old Turks. And that was very interesting. When I arrived there, as they got used to sitting in front of the gates, in front of the house there to talk… that mentality and this custom was transferred to the building. They also put benches there, there was coffee, everything… this building was different from all. And so people were close.

Since I was in a position, I and some Stihović, I say… someone from Novobrdo, one Albanian was the director of this nursery garden, Vitia, yes. I remember, Vitia. I was a functionary at that time, I was engaged in politics, I do not know how much you know… I was the Executive Secretary of the Committee […] And he comes to me, ‘What can I do for you, for you, comrade Trajković?’ That’s it. I say, ‘Listen, come on, look, take a look in front of my building where I live, people are so, you know so good. Go on and do it, plant some trees.’ And the trees now, I do not know if you know when you go before that tunnel down there are those buildings. All of these trees are… yes, that was my plan, I asked for that, and it was planted for me. No one knows that, people who lived there know. Otherwise, others do not know. That’s how it happened, that… the forest just ahead of this building.

Mürteza Büşra

JournalistNow, there is a story that’s being told, a funny one about this Clock Tower. We said that it would break down very often, and Vıçıtırn had one with a clock similar to this, but working much better than this one, now they think about it… If they would reach out and say, ‘Look Pristina is a central place, is the center of sanjak it would be well if you would give the clock.’ They suspected that they wouldn’t give the clock. What is there to do then, how would we get the clock now, how could we trick the people from Vıçıtırn. They took some dogs, really barky ones and tied some tins and stuff to their tails that would make noises {gesturing tying with hands} and just like that they released them… there around the clock tower.

The artisans, the citizens would look around and wonder what was making so much noise, it attracted their interest, the loud noises that the dogs were making. After that, you know the saying for the thieves Mehmet Aga, joe shmoe, a thief that was a very capable virtuoso, you know. A group of youngsters like this thief then went into the clock tower, took out the clock in Vıçıtırn and the citizens of Vıçıtırn never even realized it, never knew about it. They took out the clock and installed it in Pristina instead of the old one. However, after a while, they understood that the clock was changed, perhaps they might have even found out, realized how it all happened. Look at the robbery plot! Meaning, in the name of your city, for the sake of seeing your city better, what haven’t people done for it, right?

Gazmen Salijević

Human rights activistI was part of the drama section, I played for the amateur theatre Roma in Pristina, we traveled in the then-Yugoslav country, went to festivals, and I tried to give my contribution and to find refuge from that reality in the world of theatre, acting, so that we can transform {moves his hands} and become other characters. What I appreciated back then was the effort invested in putting a smile by means of comedy on people’s faces who come to the theatre, because, and I return to that, at that time life was hard, especially here, we had constant migrations, we had people who lived in difficult economic conditions, we had conflicts […]

At the time, we did the play in Romani language. We had two families {gathers his hands}, you know we took the entire concept of ‘Romeo and Juliet’, their conflict, but all of this we did through the lens of Roma life. Through Roma lens, through that, if I may say class struggle, economic class struggle inside, inside, inside Roma society. In the end, even Shakespeare in his oeuvre has depicted class struggles, conflict regarding wealth, power, love.

Xhemajl Petrovci

Electrician‘I am that Xhema from Prishtina.’ He said, ‘Are you a shehirli [townsman] or an Albanian?’ An Albanian shehirli, imagine? I understood what he was getting at, his question was, ‘Are you a Turk or an Albanian? I said, ‘I am an Albanian from the shehir [town].’ ‘Hey, I am asking you straight in Albanian!’

Minir Dushi

Mining engineer…I witnessed when the Jews were being taken that night, when they gathered them, because I was at home. A paternal uncle of mine came every Monday for Tuesday’s market day, on Wednesday morning he would leave for Gjakova. Also, the paternal uncle was there that night when suddenly the door, we had a door with a hammer knocker, they came and knocked hard, dd, dd, dd {onomatopoetic} to this day I can’t forget it. Then, yes, bim… bom, bom bom {onomatopoetic} they knocked the door down and they entered.

When they entered the corridor, my paternal uncle went outside, they told him, “Go inside!” In fact, they were Albanian SS, the [Skanderbeg] regiment… They took all the Jews, the house was left empty, they were in their pajamas and this is how they took them. We were speechless, it was horrifying.