My little sister was small when we visited our father in Peja. In Peja’s prison, which was filled with Albanian prisoners. Why do I know this? As a child, well I was quite little myself, I wasn’t going to school yet. I know because in front of the prison all the families that came to visit the prisoners gathered and had a bag in their hand {makes a move to describe the bag}.

[…] But these miseries that childhood carries will follow us throughout life because childhood [experiences] leave a trace. Luckily it did not fill me with hatred and I like that oblivion did not take over. I remember them because I never took them as personal, but I believe I share them with all the people who waited to visit theirs in prison. I share them with all the people who have been excommunicated, politically persecuted families, excommunicated by the society, a time when your neighbors did not pay you a visit because they were afraid.

March of 1998 was a month of many protests. The women’s informal network organized eight out of eighteen peaceful protests held in that month. The protests were in response to the violence exercised in Drenica, Kosovo by Milosević regime. Through protests, women activists called out to international community to intervene and put an end to violence. This series of interviews map out the history of women’s activism in the public sphere, shed light on women’s political positioning, and forms of resistance in 1998.

The interviews were produced in partnership with ForumZFD, University Program for Gender Studies and Research and Oral History Initiative.

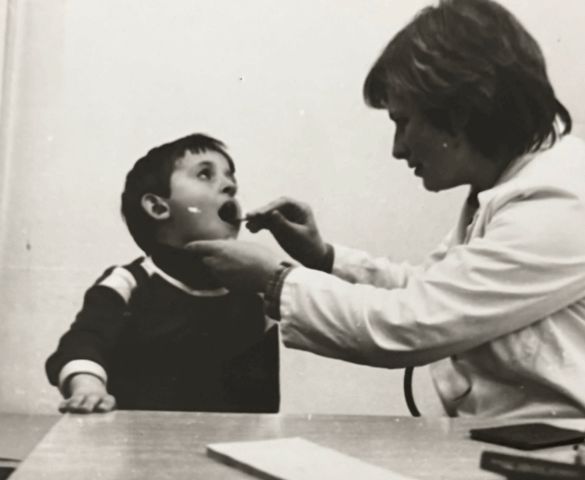

Flora Brovina

Poet/DoctorAlbertina Ajeti-Binaku

Architect…we had no tendency to give it a political connotation. It was more about giving it a humanitarian connotation, because families for days, with weeks have been under the siege. There was no free movement, you know to be able to go out and get supply, food and other things. And this was it. You know, we as mothers, as women who sympathize with mothers at that time in Drenica, who had no food for their children. […] And I remember that we were like, you know we were in a row and on the side we had police forces. Until we reached that point, then we were not allowed to go further. [Women] They wanted to negotiate, but they were not ready. So with an authoritative statement they ordered us, ‘You have to go back, otherwise we cannot risk, because then anything can happen to you and we cannot protect you…’