…I witnessed when the Jews were being taken that night, when they gathered them, because I was at home. A paternal uncle of mine came every Monday for Tuesday’s market day, on Wednesday morning he would leave for Gjakova. Also, the paternal uncle was there that night when suddenly the door, we had a door with a hammer knocker, they came and knocked hard, dd, dd, dd {onomatopoetic} to this day I can’t forget it. Then, yes, bim… bom, bom bom {onomatopoetic} they knocked the door down and they entered.

When they entered the corridor, my paternal uncle went outside, they told him, “Go inside!” In fact, they were Albanian SS, the [Skanderbeg] regiment… They took all the Jews, the house was left empty, they were in their pajamas and this is how they took them. We were speechless, it was horrifying.

The research on the Second World War in Kosovo aims to challenge the idea that there is only one truth of the history of Kosovo during Second World War, or that a unique group – whether it is Albanians or Serbs, nationalists or socialists – possesses the truth. Through oral history interviews with the war generation when possible, or their descendants who deliver post-memory testimonies, we are engaged in hearing all stories, including those which remained below the radar of the official truths – whether held by the state, a nation or a political group.

Minir Dushi

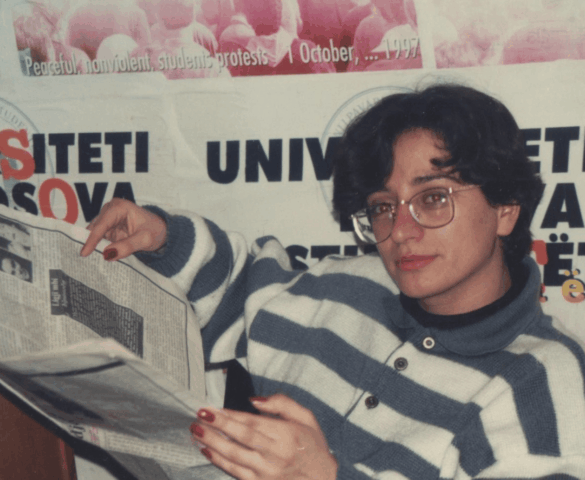

Mining engineerMihane Salihu – Bala

Civil Society ActivistMy family is a mixed family. My dad died Muslim and because he fasted during Ramadan he was unlisted from the party. Whilst my mom is an Albanian Jew. In our family we were brought up with all traditional religions. Most of us, kids, are baptized. So we are an interesting mix, I would say, of different cultures. Because in the end religion is something you do just for yourself and not for others. […] To grow up in an environment where your cousins have different religious belonging, and you have the possibility to make a different choice that is… It wasn’t well received at the time. […] I remember when we had different holidays, especially Eid Mubarak, the entire neighborhood made baklava, my mom also made baklava. Other holidays came, my mom prepared a more special food, but she was subtle, so it was interesting. What I remember are September’s feasts, the feast of baking bread and cooking wheat and grape and all that. That’s when it started getting interesting, ‘Ah the grandparents are coming…’ and it was interesting. It was later that we understood it was a different tradition.

Votim Demiri

Head of Kosovo Jewish CommunityAfter the Second World War, we lived in a secular state, even now it is a secular state, but the majority of people were atheists then. What do I know about religion? I know it from my mother at home. Mother would tell us when there were Jewish holidays, she cooked what needed cooking that day, but [this stayed] within the family. Let’s say, when we had Passover, whenever my mother cooked rice and chicken she gave me the thigh, but on Passover she only gave me the wing because according to the Jewish tradition children should be taught how to fly. I would complain, ‘Bre mama this and that… can’t I have [the thigh]?’

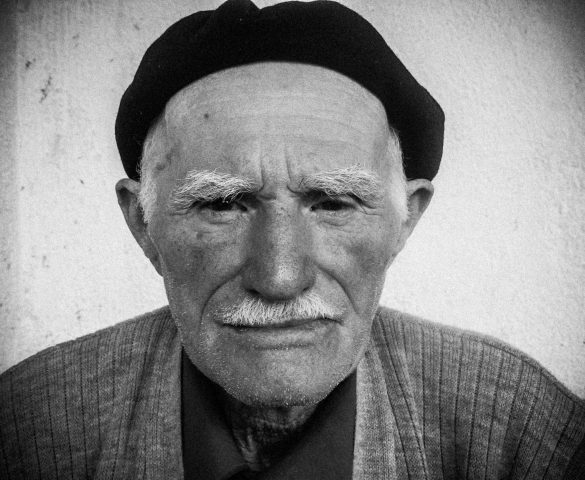

Zeqir Sopaj

The Second World War VeteranBecause Fadil [Hoxha] said, ‘We also have to give something. When the sofra is set, we have to place something on the table. Whose is this? It will receive justice. We in Kosovo are few in the world, but an egg, that egg will receive justice. […] We are fighting together, Serbs, Albanians, to remove fascism and the occupier. When the war is over we will be, everyone will receive what they deserve. We will be with Tirana, Tirana will work with whom they wish. We fought for this, we knew this, Kosovo Communists knew that we will work with Tirana, not with Belgrade.’ […] ‘When the war is over everyone will be rewarded. We, Kosovo, an egg, that egg will receive justice. Someone offers a goat, someone a sheep, someone a bull.’ ‘But we are few, bre.’ ‘That indeed will receive justice.’ But we never received it, from ‘48 on.

Adem Pajaziti

EconomistIn this interview, Adem Pajaziti talks about his father Shaban’s experience of one of the most obscure episodes of partisan violence at the end of March 1945, long after Kosovo had been liberated from the German occupation. This is the story of the forcible recruitment of thousands of Albanians from Kosovo; of their desperate march across the mountains to the Montenegrin coast; of the torture to which they were subjected during the march; and the mass killing once they arrived in Bar. Before his death in 2007, Shaban gave an interview to his son Adem, which we also propose here. […] It’s interesting that the war connects people very much. In our village there were ten, they all survived. And some migrated, they moved elsewhere, I think to other cities in Kosovo. But those who stayed there befriended each other and held each other close, and they always called each other war comrade, they did not call their names, but war comrade, ‘This war comrade, war comrade.’ But they never got together, and even if we took the initiative, or tried to get them to talk about it, they never wanted to explain. Individually, they would explain, they would tell how it happened; when they were together, they didn’t want to and they would say, ‘Did you get us here to judge us, or what do you want? We won’t explain it, we won’t tell it!’

Shaban Pajaziti

Survivor of the Massacre of BarThe guy from Gllabar wanted to drink water there. Then the officer, the stražar, hit him with the dimgjik [butt] of the gun, and he turns the gun to him, he turns the gun to him and shoots the stražar to death. Then his friends caught the guy from Gllabar and took the gun from him […] The officer was just cleaning his sweats when he said, ‘Deset za njega [Ten for him], ten for him, there will be a shot for the one who killed him, he was a partisan from ‘41.’ As the four of them were coming in a line, he said ‘Još deset [Ten more], ten more,’ he said, ‘more.’ He caught him and they left, they left, they became ten people, 19 people, he caught me as well, but thank God this crossed my mind, one of my friends had his rucksack, he was just two meters far from us, and to me it sounded like he wanted me as well, and I stood up, I took my rucksack and turned around, I joined them and sat down. 19 went. They took 19 of them.

Rexhep Bunjaku

Former Political PrisonerThat it would come to that, that I would make a one hundred and eighty degree turn, to confront Yugoslavia, was due to the story that this Jovo Bajat [told me] of how they killed Albanians. Until May 9th, when Germany capitulated, they killed and massacred without trial. […] One night he tells me, he says, ‘We made them lie on their back {he opens his arms, showing how they lay down}, we would nail him down like Christ and with a baton we would hit the chest, and blood splashed to the ceiling, we would get excited, get into a trance from the pleasure of killing Albanians.’ […] I covered my head with a blanket, and cried like a child. This is when I took an oath that I would work against Yugoslavia, be it with god or the devil.[…] I returned to Ferizaj. From Ferizaj then, I did what I could, took a sick leave from OZNA. I pretended to be sick with tuberculosis. But I did not have anything. They transferred me. […] I returned to Kaçanik. There I became head of the Sector for Internal Affairs, in Kaçanik. And a few friends, without my knowledge, were connected to the Central Committee of the NDSH, the Movement, in Skopje. And one day Hajrush Orllani came. ‘Rexhep…’ he said, ‘Today we will meet to establish the Kaçanik Committee of the NDSH.’ I looked forward to it. And so we met, seven people. We talked, we wrote the program, we formed the District Committee of the NDSH in Kaçanik.

Enver Tali

Political ActivistHowever, I went to my neighbor’s, my neighbor’s son was four or five years older than I was. ‘Come,’ he says, ‘let’s go and hide.’ Where should we hide? They owned horses. Because of the horses, they had grass sheds, what do they call it, hay, so he says, ‘Come, let’s climb on the hay shed, and crawl inside.’ ‘Okay!’ [I said], being younger than he was. My mother didn’t know, nobody knew. We got up and climbed into the hay. He went to a corner of that room, removed some grass and entered the hole, just like that, he hid on his feet, he put the grass on his head. […] I couldn’t do what he did since I was younger. I gathered some hay and spread it, I lied down, covered my head with hay, and my feet were outside. When they entered to search for someone, they didn’t find anyone in the hay shed. They found me, and drag me by my feet. They took me, got me out of there and took me to the yard, … not the yard, the street. They shot a lot of people by the stream. There were seven or eight old people from my neighborhood tied up, I knew them because they were from my neighborhood. They tied me with those old people, to shoot me. Three people were guarding us with some kind of Russian automatics… machine guns that can stand on the ground on three legs. And they were armed up to their teeth. […] They killed what they could, so it was our turn to be killed. However, behind our tied up backs, Shaban Haxhia’s partisans were approaching the bridge on that stream. They were armed. ‘Don’t move, don’t’ move, don’t move!’ They yelled. They raised their hands. ‘Don’t move, don’t move!’ They raised their hands. We turned to see [them] and they had the five-pointed star, how could we trust them. But anyway, because they spoke Albanian, we had some hope. When they came closer, ‘Who are these?’ ‘Enemies,’ they called them, ‘neprijatelj, enemies, enemies.’ […] He hit me on my arm and got me up, since in my condition I was weaker. He got me up a bit and said, ‘Is this child an enemy too?’ He had a gun in his hand, he killed the three of them without a word, those who were waiting for us.

Enver Topilla

ActivistThe village as a village, now, it has more soldiers, but had you asked me, if I was a factor… the whole Albanian nation was in the war, everyone is a war veteran, I’m speaking for myself now. To differentiate them like this, I don’t like it. Because even the mother who gave away her bread, and the one who sheltered children, and even the man who was never separated from his family, and the one who knew he’d be killed, they never gave up. And because the Albanian nation was very small and many became soldiers, it would have been better had we done like in France, make them all soldiers, war veterans I mean, veterans. The Yugoslav system was very bad, but if a woman cleaned somebody’s shoes or a pair of socks, they wrote down that she helped the army. Our Albanians worked for the struggle, from the academic to the farmer.

Sylejman Çollaku

BakerWe had the bakery in Pristina, we had to leave it behind, the Germans came and we had a falling out with the landlord. We went to Ferizaj with our dad for work. The Germans were there, they were there as well, although the Italians were [the occupiers]. They visited our bakery, I was with my dad, he was selling bread and I was helping around. An officer walked in with seven bags of flour, each bag had German letters imprinted on them. He approached me, I made a mistake, I know, I was asking for it, he said, ‘How many kilos of bread do I get for one kilo of flour, baked by tomorrow?’ I told him, ‘Eighty kilos of bread for one hundred kilos of flour.’ He knew how much flour he was putting in, you get one hundred and forty kilos of bread [for that much flour], and he placed his hand on his gun, {places his hand on the belt} I remember it clearly, as if it happened today. He felt sorry for me, because I was young then, so he said, ‘Grab the bags!’ The bags weighted one hundred kilos. There were two stairs to get into the bakery from the street. When I grabbed them, only my heart knows how I got it inside. When my dad saw me, he got up to help me, but the officer did not let him. I dragged the bags of flour inside with great difficulty, but he never ate that bread because he left for Germany, they all left that same night, the flour stayed here. The white bread and flour remained, the German went away. This was the story of the German.