Oh, that was a great moment, even from, from… it was a Saturday when NATO came, so it was June 12, Saturday… June 11 was Friday, no… Yes, exactly on June 11, Friday, June 11, Saturday. Usually, I didn’t sleep, but from the window of where I lived, you could clearly see the house, and when I saw the tank, it was early. Oh, until this day… now at this moment I have… I felt a lot of happiness, I said, ‘Oh, wife, NATO came. Let’s salute them!’ And I was trying to run until I saw the tank, but when the tank turned, I saw the tank and I put my hands up, and it was miraculous. Something incredible. Yes, even for me, it was incredible that such a crazy atmosphere was created that people forget. For me, that was something unbelievable and…

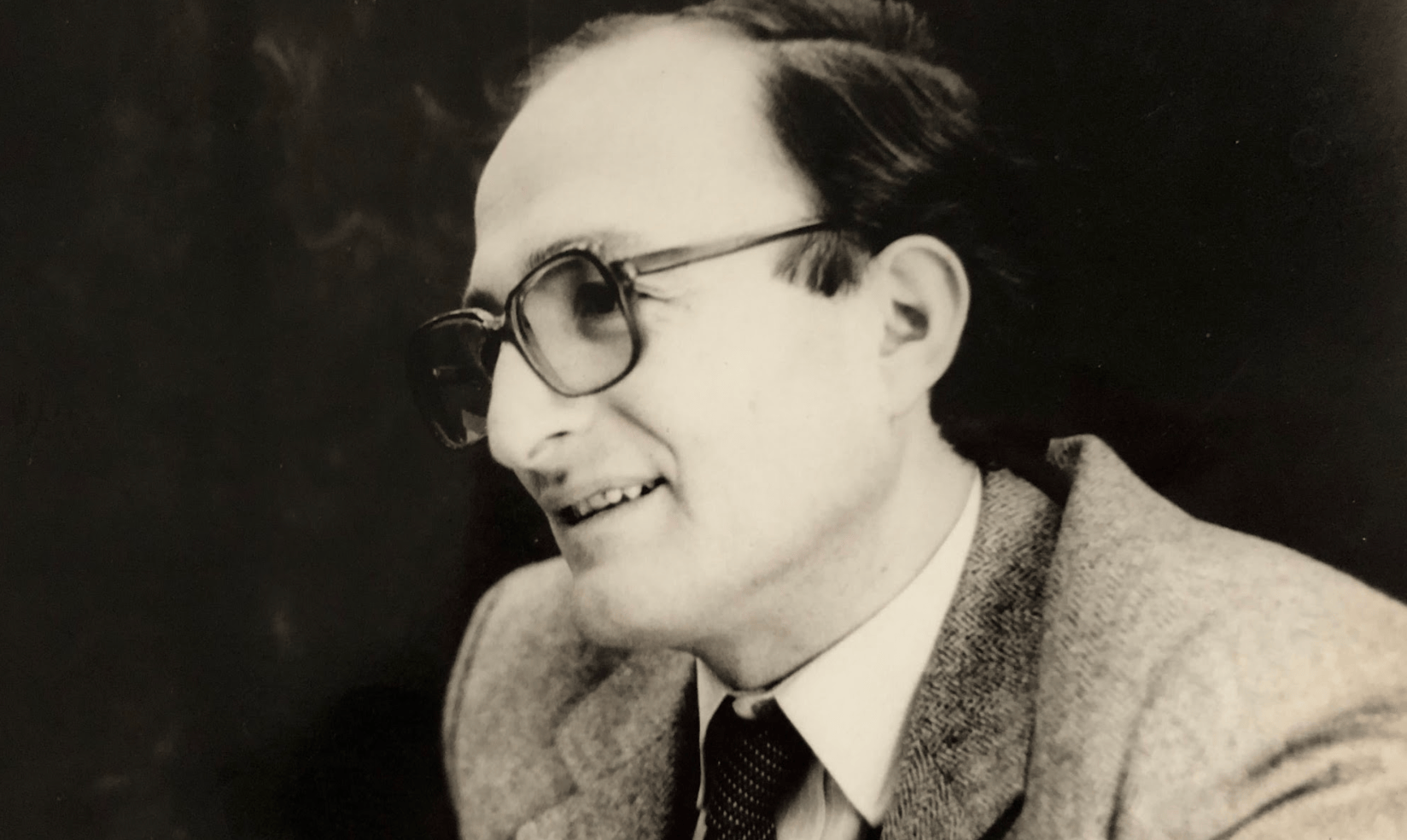

Skender Boshnjaku was born in 1942 in Peja. He has received his master’s and doctoral degrees in psychiatry from the University of Belgrade, Serbia. Upon graduation, he was employed at the Pristina General Hospital as a psychiatrist, and worked there until his retirement. Today, Mr. Boshnjaku spends his time reading, writing about art and interpreting city graffiti. He lives with his family in Pristina.