Part Two

Ebru Süleyman: These events that you have talked about, they were festivals?

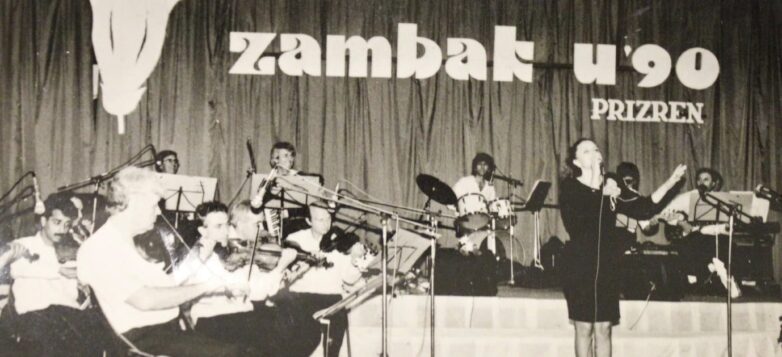

Sevim Baki: Kosova Akorları was a festival, yes, but Prizren Zambağı was held once a year, it was called Lily because Prizren was considered a cultural place and it has a river. On the other hand, Kosova Akorları were organized by our professional Pristina Radio, it was mandatory to have songs in three languages, there was always one or two songs in Serbian and Turkish. I preferred to take the stage in the light music section on the second night, but sometimes I also sang modern Turkish music on the first night. The first night was all about art music and the second night was light music, I participated in both with Mr. Şemsi’s compositions.

I remember the offer from Tomor Berisha twice, he said, “Would you like to sing in Albanian, come on, you have to change your genre, everybody loves you, you are really famous.” But I didn’t accept the offer because the Turkish community didn’t have an artist, that was why, if I would have thought about financial gain, perhaps I would have accepted it. But I said, “No. You already have a lot of artists, if I join you, what will Turkish community do?” And I didn’t go.

Ebru Süleyman: Was this festival held in Pristina?

Sevim Baki: Yes, always, because the central radio was in the capital, it was always held in the Red Hall, they would make the hall even more beautiful than it was, all live TV would come there, it was a really precious and beautiful festival.

Ebru Süleyman: That time, this Red Hall, Boro Ramiz was really popular, right?

Sevim Baki: It was popular, really crowded, I remember and I also have pictures. There were a lot of people who wanted to attend the Kosova Akorları festival. Well, I was really lucky because I was always invited and also the first one to attend. After that I had a friend called Violeta Rexhepagiqi, Armend Rexhepagiqi the siblings. They sang really modern and universal songs, they wanted to enter the Eurovision Song Contest in Belgrade. Then she also called İvana Vitalić together with me, Sevim Baki, we organised a band named Vivien. She was the one who organized everything, she said, “Sevim, I wish for the three of you to sing a song in Albanian and Serbian and enter the Eurovision Song Contest.” So, in year ‘86-‘87, we attended the Eurovision contest in Belgrade. We couldn’t have a place in competition but at least we attended.

Ebru Süleyman: Can you share with us your experience about this journey?

Sevim Baki: It was really strange because I have changed a lot, she made us look like her. A haircut and purple hair {showing with her hand} I don’t know how much you know about her but she was a hippie. Everyone dressed how they preferred, but I tried to blend in, I had gloves, one of them short, the other one long, I tried to create a hippie look. It was good to be in a completely different environment.

Ebru Süleyman: Was it the first time that you did something together with a group?

Sevim Baki: Yes, it was the first time that we sang a song in three languages, but in the past, I had participated a lot in tours in Kosovo organized by Albanians. Someone would organize 15 days of tours in Kosovo, but it was a law that it had to be held in three languages. Now if there is a concert with five or six Albanian artists, there should be a Serbian and a Turkish artist at the same concert. Nowadays you can see that the amount of work you do depends on how many supporters and sponsors you have. For example, now RTK doesn’t have any Turkish music program, before when there was a music program, there had to be musicians from other communities. But now there isn’t anything.

When you watch TV, it’s only in Albanian. RTK 2 is only Serbian, and there is only news left in Turkish language. Except that, there is a programme called Mozaik, but this last few years, even though I had a lot of activities, I didn’t participate in that program. I don’t know what could be the reason for this, but I think that they aren’t doing their best because they are not inviting us, the Turkish community there. They are saying that they have a low budget, they don’t have support? I don’t know because I am not involved, but I can say that there is a difference between now and the past.

Ebru Süleyman: So there is a big difference in terms of activity and representation?

Sevim Baki: Yes, a lot, as I said, before it was an obligation to represent everywhere, “Brotherhood Unity, Brotherhood Unity…” If there was a program organized by state institutions, even if I was really busy, they said, “It is obligatory to have Turkish music, and we really want you to perform.” So I would attend tours.

They would pay some of the expenses, if the road was long, we would have two concerts, for example, one in a village, one in a town, one in a village, one in town… If we were going to perform a concert in Gjakova, we would first perform in Klina, then Gjakova, if we were going to Prizren, we would first perform a concert in Suhareka at four, then at seven o’clock, in Prizren. At those times, all the halls were full of people, I can’t deny that everybody absolutely adored me, I feel bad that I don’t have any videos of that times just for the sake of memories, I have only a few pictures, the ones who organized these events, maybe they have pictures, I don’t.

Ebru Süleyman: Which year was it?

Sevim Baki: All of them, from year ‘86, ‘87 until ‘88. Then school was over, I got married, I got a job. I immediately started working as a music supervisor in Turkish archive programs. Besides being music supervisor, I worked as a presenter and we organized programs together with artists. At the same time, I would go to the radio department and decide on a certain week, so we could practice and make new records. Also, everybody knew about the New Year’s Eve program, it was really hard, we would start to get ready from the ninth month. Now we have TV and radio, but not a trace from those programs.

Ebru Süleyman: If we talk about music style a little bit, you mentioned Turkish classical music, light music and modern music, can you describe the differences between them to people who may not know them? You can describe the technical details, as you wish.

Sevim Baki: Turkish classical music is a tune which contains a system of melody types, not everybody can sing Turkish classical music, you can be a really good listener and you can love it, but as I said, not everybody can sing it. If you look back in the old times, this type of music has started when the Ottoman Empire arrived in the Balkans, no, it’s Rumelian Turks {doing the sign with her hand}, I’m sorry I got confused, it’s Rumelian Turks. Because I wanted to distinguish between Turkish classical music and our Rumelian folk music. You can not use every instrument in Turkish classical music, even that it was influenced by the West, it evolved with different music arrangements and stuff. Also, I remember Mr. Rasim, he made us practice a lot.

In Turkish classical music, there was Muazzez Abacı,[1] Zeki Müren,[2] Ahmet Özhan[3] and Zekai Tunca’s[4] songs, we used to listen to them, he used to say, “Listen to Hamiyet Yüceses and gain experience…” Even now when I listen to something, I always know what music is it because I really have gained experience with all those cassettes and tapes, we really worked hard. Whether in Gerçek or in radio, I had a great repertoire.

I am pleased with that, there are a lot of songs, but I think that I know most of them, it’s rare when there is a song that I don’t know. Like I said, Turkish classical music can be sung only with instruments like violin, qanun, oud and frame drum. On the other hand, Rumelian folk music, which we used to sing a lot and like it a lot because it’s local, it has started when the Ottoman Empire arrived in the Balkans and got influenced by them. It has differences because every region and language has its own writings, melodies and instruments.

Ebru Süleyman: So I guess Rumelian music is more based on community and folk, and Turkish classical music is based on education?

Sevim Baki: It’s based on education because every song has its own system of melody types and the melodies are really important, but unfortunately I couldn’t find someone here that could teach me these melodies.

My husband knows that very well, why, because he plays an instrument, he is adept at learning melody types because he has worked with ambitus and scales. I have usually worked on my voice, that is why I couldn’t understand much of these melody types. I guess here we always learned to listen with our ears, if I could have some singing lessons in Turkey, I would definitely learn these melody types. For example, here, sometimes I am scared that I will get so embarrassed in front of a Turkish artist because I don’t know those melody type systems. But unfortunately there was no one here to teach me that.

Ebru Süleyman: Do you know how Rasim Salih got interested in music? How he learned these melodies?

Sevim Baki: Well, I don’t have any information about him. Now he is working on a program with his grandkids. As I understood, he is one of the first artists who came from Mitrovica, he overworked, established, gathered people and engorged them a lot. He had people with good music ears around him, as my husband told me, he just started working with notes in the last few years, before that, he just had a really good music ear.

Ebru Süleyman: I am curious about Rumelian music, which I guess was carried by people who migrate from one word to another, from one family to another, and from one generation to another. But Turkish classical music is based on education, so how and when it was formed in Balkans?

Sevim Baki: No, I guess we listen to Turkish music because we see Turkey as our homeland. I remember we knew every Turkish artist here, you know with all the shopping. I remember all the drawers were full of tape recorders, we would buy cassettes, not CD or something, but a lot of cassettes. When we would visit Turkey, I couldn’t stop myself from buying new 20 – 30 cassettes. But now there is no trace, I wish we protected them. We would give them to our friends, “Oh you have it, let me have this for a week.” So they were left in some places, broken. Now I feel bad that there are none left.

I guess it can be it, because Kosovo – Turkey relations were always decent in every aspect, whether watching Turkish TV programmes or visiting Turkey, it was something that we did more often than now. Really, there were no cell phones, but I do remember everything, also with the Gerçek Association, we participated in a lot of festivals in Çorum, Silifke, İskenderun, Kastamonu.

Ebru Süleyman: Who was active in Gerçek in ‘80s? I mean who taught folklore, who made the rehearsals for theater, or who made organizations for music?

Sevim Baki: Well I can’t remember who was responsible for rehearsals because it has changed a lot. I know there was Ercan Kasap, Mrs. Aliye, my father played in the theater for a little bit. My sister Senay also played. But who was the director, I cannot remember.

For teaching folklore, the old dancers were there, I also remember a guy named Kemal, we used to call him Kemo, he came here as a student then stayed here, discovered Gerçek, he knew folklore dancing, he was really into it. In Turkey, as you know, every kid either learns to play an instrument or dance folklore or goes to school choir, this is something that I adore. They promote culture and activities to the kids. He came here to spend his time teaching folklore, in that period, together with local dances, we started learning modern Turkish folklore. Çepikli,[5] halay,[6] efe[7] are the some of the dances that we learned.

Ebru Süleyman: You told us about Geçek period, then music school, radio recordings and New Year’s preparations, so you started working again in radio in the ‘80s or ‘90s ?

Sevim Baki: In the ‘90s, I got an offer immediately after I finished my school, “Sevim, after you finish school, we want you to come here because we are in need of a music supervisor.” As an artist, I would go there to work on the music recordings as a hobby. At any organization that state radio made, when they were in need of something for Turkish, they would call me.

I went to the professional classical choir for a while, I worked for three months, I liked the notes and I sang opera with notes two or three times, actually I was looking forward to working there but it never happened. I couldn’t finish university because, after high school, I immediately started working, I got married, then there was the war, I worked for nine years as a music supervisor. When I was in the third class, I dropped out of university, I guess I had kids, we were relieved, everything was just fine, I had work, a house, kids, I had some activities but not as busy as before.

I started to get behind from Gerçek. There was new generations. I only attended as an artist, to TV filmings and was only invited to special concerts. It was really a stable period because, as I said, I had kids, then the war, after the war, we didn’t have our jobs.

But it wasn’t a long period because I was active, my father also was really active, he knew everyone, private contact radio, multiethnic contact radio. They started Serbian, Bosnian, Turkish, Albanian, Romanian news and music programs, so they hired us there. My dad told me about this and then I started working there as a music supervisor, I saw a few of my Turkish friends working there, we worked there for 18 months, then it shut down again and I was unemployed again.

Ebru Süleyman: So this is right after the war?

Sevim Baki: Yes, just right after, right after working nine years, there was neither an orchestra left nor the artists. Also, our journalism program, news program never opened. Then, after one or two years, the news program continued with five or six people. Now I don’t know how many people are there. There some broadcasting, but I don’t know the details.

There is no previous wealth left, there is no trace of old pieces. Because they are not using them often, instead, they are always relying on the old records. We the youth could only make a music record if we had sponsors. And what happens then? There is only one music clip on your CD, not even connected to any institution.

Then I realized, no matter where I go, I couldn’t find a job with my music school diploma and Turkish language. “Music school? It’s nothing.” For the sake of doing something, I registered at the Turkology Department at the Philology Faculty. I was lucky that there was an opening in the Human Resources Department, they were searching for a minority. So in that period, I was in a rush. I was working as a civil servant at the Ministry of Environment and Spatial Planning. This year I finished my 10th year here, and I am working with a really nice unit in the Human Resources Department. I have learned new things.

In the same period, I had many difficulties, three children, family, being a married woman trying to manage both university and work was quite difficult, but thanks to my family, they were always there for me. Sometimes I wasn’t able to cook, sometimes I was sleepless because it was not easy to pass exams. But I graduated just in time, I didn’t want to be a minority without a university diploma. Because they are looking forward to saying, “Look at these minorities always employed without a university degree.” So that is why I made a promise and graduated. I am working here, as I said, but again, there were some choirs opened two or three times, I guess it was called Tan choir, Meliha Hüdaverdi and Sebiha Hüdaverdi were the organizers.

Ebru Süleyman: Is it after the war?

Sevim Baki: After the war, they started to establish choirs, I participated in some of them, but I didn’t like the method they followed. Perhaps, when you have enough experience, when you are really into what you are doing, you realize all missing aspects. If you want to be involved, it can backfire because you are young. They needed help, but when it came to something more professional, I was not allowed. I couldn’t stand it, I tried one or two times but I couldn’t do it.

Then some of my friends started to insist, “Why don’t you organize something?” I said, “All right, but how?” We don’t know how. I was always used to being invited but not the one who invites. Also, at that time, we didn’t have a proper location, there was the Gerçek Association, which I really wanted to work at, but unfortunately, in winter, it’s really cold, there is no kitchen, nothing, if you want to organize a concert, there isn’t any support, there is no budget.

Meanwhile, we really liked literature in university and started going to the Yunus Emre Institute, you know the cultural center related to the Turkish Embassy. I saw that they were interested in new projects, I consulted with professors, and they said, “Yes, we really would like that, you can work here and organize a choir here.” Now, there are almost 20 women who know the Turkish language in choir, maybe most of them are Albanian, they say that they are Albanian, but they speak Turkish very well. Also they really like Turkish music and they want to learn Turkish music.

From Rumelian music to articles, I am trying to pick something and create a repertoire of songs that they already know and are easy to sing. In order to teach Turkish music, we established this choir in 2015. We have built a really nice friendship there. Sometimes we are not rehearsing but we still have our friendship, even if we don’t do anything, our friendship will remain. They are putting their heart and soul into this work, because of that, I try to organize new projects, dresses are made, we have a CD as support.

Now we were working on a video clip, but if we don’t have any supporters, only the song will be published. We had concerts, and I really want to thank the Yunus Emre Institution for their support and also the Ministry of Culture because they also open new projects once in a while and support us with a small budget that we can use on our organizations. I am really enthusiastic about this crew that I could gather. Everybody is working with their heart and soul without expecting something in return, just like a hobby, I hope that one day we can get the benefits of this labor that we have done.

Ebru Süleyman: In choir, are you trying to sustain local pieces that you have mentioned before? Şemsi Mecihan…

Sevim Baki: No, I am not using them. There are modernized records of them in radio, I hope they still remain there. Although I transfered most of the records to CD, I wanted to have them in my own archive. But I couldn’t get them all, on paper, they claim that they have all the records but… I cannot say that there is anything exciting in the chords and compositions in front of the audience. They are quite nice but really modern.

The compositions that we sing are sometimes from Prizren folk music, Rumelian folk music and Turkish folk music, this time I am also teaching the melody type systems in Turkish classical music because my husband is also by my side with his instrument. For example, I am saying, “This time we will sing from nihavent[8] melody type, in the second part we will use hicaz[9] and then rast[10] melody type…” All the melody types have their own rhythm, some of them are really slow and some of them are fast. So I am working on that, but still it’s very exciting that they know all the compositions that we are working on. What I want to say is that they adore the songs, and I am trying to teach them some special things for special occasions.

For example, for Ramadan, we made a repertoire with one of the best chants. If there is a need, we would organize a program. Thanks to them, they published the repertoires into a book, there is everything, we use it often in our organizations. As you know, Rumelian songs are more preferred here, that’s why we want to change it and have more options.

Ebru Süleyman: Which hall did you use the most for your performances? Before and now.

Sevim Baki: In Pristina, I remember the Red Hall the most. Our Turkish community concerts and also the Choirs Festival was held there because it serves the needs, it has a nice stage, really good hall for the audience. I remember the Red Hall. I remember the theater less. I forgot everything, but I know the JNA Hall, Jugoslovenska Narodna Armija [Yugoslav National Army], Yugoslavia International National Hall, but it belonged to the Army at that time. After having that place from the UN, it belonged to the Army. I remember that city hall and Gerçek’s events were held there.

{While counting} There, Red Hall, there was an amphitheater in Boro Ramiz, really high and green {explains with her hands} it was really a special place, now there is Cambridge School in that place. Now that is out of order, not a lot of people know that place exists. Now when you step down from the stairs in red hall, that was the way to the amphitheater. They have closed off that place now, there is Cambridge School. So you would step down and there was the Green Hall, the amphitheater just like a cinema, we used that place really rare. There was also a hall of sports, really big, they call it Bir Kasım [sic.] [October 1] now right? That hall, {explains with her hands} it was used for grand concerts. I don’t remember if we ever visited there with Gerçek, but I sure did visit with grand concerts, tours. I can’t remember any other place.

Ebru Süleyman: If you want, you can tell where you spent your youth, where did Pristina youth hang out?

Sevim Baki: Well, what can I tell you about our youth, our place was the Gerçek Association. We made friends there. As I said, we were three sisters always hanging out together. If we wanted to go out, we would go out from Gerçek, “Come on, let’s go somewhere to drink coffee.”

There were our older friends, musicians, for example, people from my husband’s band. We also met there with my husband. Those times when we were friends, they used to say, “Are you coming?” And they would take us to Grand Hotel or Božur [Hotel] for drinking a nice coffee. There was Restaurant Rugova, right there where the old Maxi was, they used to hang out there a lot. It was fine, not bad but we the younger ones didn’t like these places, we would only go because our friends were there and it was warm in the winter…

Ebru Süleyman: I guess the cafe in Grand Hotel was really popular back then?

Sevim Baki: Yes, it was really popular thing to hang out at Grand. It was really odd for me because I was really young, what was I doing there? But, as I said, our friends used to go there, so that is why. Then in summer korzo[11] was really popular. There was a group of friends always hanging out in the same place, we would mock them by saying, “What are doing here? Are you protecting the trees?” Everybody knew their spot, our spot as a Turkish community was in front of Foto Nesha.

When we would go out at night, we would go to Xhani or Cannabis, I remember these two cafés. Xhani was on the corner of Tri Šešira [Three Hats], we would sit outside. It was always very crowded, there was music, so we would hang out there. Also there was Cannabis in the new district in Kičma [Spine], we would hang out there a lot. I will be honest, I didn’t like these cafes, these kinds of music, disco. I don’t like disco, nowadays, if you ask the youth “What kind of music do you like?” Everybody has their own taste of music, I never enjoyed English music. So like that, I would go out but I didn’t enjoy it a lot, sometimes I wouldn’t even go out. Like I said, in youth, there was a lot of work, also school and Gerçek, so we would return home early. Also our parents wouldn’t allow us to stay out later than 9:00 – 10:00 PM. We had to return home, therefore I didn’t have a disco life.

Ebru Süleyman: In these places, they used to play pop and modern songs right?

Sevim Baki: Yes and always English, rock, pop music, I didn’t like these styles. That’s why I cannot say much about it. But I remember these two cafes, we used to go there a lot, every time we were out, we would go there. If we go to Gerçek two times in a week to practice, after practices, we would go out. And then after school, when we were going out with my husband, we started hanging out in other places, not very popular, but in quiet cafes.

Ebru Süleyman: Your kids were born before the war, right?

Sevim Baki: Yes, I have two sons Mennan and Enes, they were born in ‘91 and ‘96. At that time, we had to get out of our house with them. We had luck because Kosovo was bombed when we arrived to Bulgaria. My parents stayed here, my father in-law was here. They didn’t expect any of this, but it happened. We stayed in Istanbul in the Silivri area for almost two and a half months, thanks to our relatives, they opened their houses to us.

Ebru Süleyman: So I guess people here didn’t want to believe that this can happen.

Sevim Baki: They were talking about war, but we didn’t believe that it’s going to ever happen. Until it really happened, we said, “It can never happen, they won’t let this happen, Europe and America won’t let this happen.” We only heard people talking, how can I know about war? I was very young, 22 or 23 years old. But unfortunately, it happened, my parents have seen the war. Even one night, all the windows of the house were broken…

Ebru Süleyman: I guess they bombed the post office?

Sevim Baki: Yes, also, there was a car in our neighborhood that had exploded. My parents, they were terrified and stressed out, but they didn’t see much of it. Even somebody tried to pillage the house… maybe the neighbors or I don’t know, when they saw my parents, they ran away. Because they stayed there to protect the house and a lot of our relatives also stayed for the same reason. I remember my sister was pregnant, we took her with our car at the last minute, and she had her baby in Turkey.

After that, everything was okay, we sure had difficulties for two and a half months. We couldn’t wait to return. I didn’t experience anything bad in my house. There were some relatives of my husband in our home because they were kicked out of their house, they had searched for an empty place to stay inside. Even my father-in-law was there when they came, so he left them the house. Not even a needle was missing in our place, they didn’t pillage or attack the house.

We dreamed that everything would be the same after the war, but unfortunately, we couldn’t get our jobs back. I wouldn’t believe it if I even dreamed it. Every door was closed in my face, they had no pity for anyone. I was working in the same institution with my husband, therefore, we both were unemployed. We had kids, every time I went to the radio where I was working as a music supervisor, they said, “It’s over, there is nothing for you here, when everyone returns, then you can come!” We were waiting for an answer from the authorities, but nothing ever happened. Everything that was old was wiped, new units were open and new personnel were hired, five or six new people.

Ebru Süleyman: What happened to the work that you have done at the old radio?

Sevim Baki: Nothing. I have only managed to find the documents that I have worked for a few years ago. I have worked for nine years but only six years of it were registered. The benefit I get from all those years was only a day off. That is it, nothing more. Thanks to my husband we never were in a really bad condition, he always worked, he always worked somewhere, we even made gains. Maybe it was for the best, but to work at an institution and to represent a nation, it was something else, it was a privilege. Then you slowly realize that you have to get up and do something for yourself. If you want to do something, you have to organize a project, apply for funds and make it happen. Now this project may not have a lot of followers but we are trying to gradually achieve success.

Ebru Süleyman: You have to take initiative…

Sevim Baki: You take the initiative, but there is no support. It’s hard to find support. We were used to get support from state back in our institution. But now we have our political party, I don’t know where their budget comes from, but nobody is interested. Nobody cares, some values get lost because of disinterest. Everyone is trying to do something unique, everyone knows your job and tries to manage you, but unfortunately, my husband and I, we didn’t allow something like this and I think that is why we couldn’t make progress here.

Ebru Süleyman: So I think that stable support from the state is very important for art, to give them a proper place to perform their art, right?

Sevim Baki: Back in time, the state even made opening a place for art obligatory. If it’s 80 percent Albanian, five percent or ten percent should be Serbian and Turkish. I think that it had to be like this at state institution radio and TV. But the funds are not being used for us, recently I realized that New Year programs became so monotone, that is why they cancelled them, there will be no more New Year’s programs held on the RTK channel. They invited us until last year. They asked us, “Is there something new?” And then I started to ask them, “What possibilities do you offer to us?” I mean, they don’t provide us with anything, you need to have your own car for transportation, “We can’t even provide a cup of coffee,” they said. “Then why do you invite us?”

The studios are so simple, there is no make-up artist, no hairdresser. Which is essential, if you bring 20 women, there, at least, a hairdresser should be there. The stages are awful, they have nothing to do with scenography. Comparing with other Albanian programs on RTK, I don’t think it’s fair… they have the best quality in everything but minorities like Bosnians, Roma, Turks, they have bad conditions… So because of that, I hope they won’t mind but I will not participate in any organization again, never again. If I want to do something, I will find my own sponsor and something that is worth doing because we don’t have the proper conditions. I think it is not a must to organize new events.

We have people who manage us and rent good workspaces just to stand next to us, as a Turkish committee, they have to rush and do something on behalf of the Turkish community here. I think we have done a lot on behalf of Turks, but the values are nowhere to be found. I mean, you keep going on, but when no one opens a path for you or helps you then, where has your labor gone, what are you working for, you know what I mean?

Ebru Süleyman: So art has become something that you do only for yourself? It cannot reach society at large.

Sevim Baki: Yes, it cannot. I think I have already done something, especially in recent times, I have tried again and again, but we are still in the same place. I don’t believe that I’ll ever give up because of the women’s support and desire, they are always encouraging me, so I’ll always try to do something for their sake.

Ebru Süleyman: Thanks a lot for your time and stories.

Sevim Baki: I hope that we created a good program, I hope you can use these values.

Ebru Süleyman: We also hope that all of this will be recorded and passed down to history.

Sevim Baki: Inshallah, thank you.

[1] Muazzez Abacı (1947) is a Turkish singer trained in Turkish classical music. She has been active since 1973.

[2] Zeki Müren (1931-1996) was a Turkish singer, composer, songwriter, actor and poet. Known by the nicknames “The Sun of Art” and “Pasha,” he was one of the prominent figures of the Turkish classical music. Due to his contributions to the art industry, in 1991, he received the title State Artist.

[3] Ahmet Özhan (1950) is a prominent Turkish classical music singer, conductor, and actor.He started singing in Turkish clubs when he was about 18. He performed concerts all around Europe, the US, and the Middle East with his group.

[4] Zekai Tunca (1944) is a Turkish classical music singer. In 1998, he received the title of State Artist given by the Ministry of Culture and still works as a soloist under the Ministry of Culture.

[5] Fast pace folk dance of Gaziantep.

[6] Folk dance styles in central and southeastern Anatolia.

[7] Folk dance of Aegean Region.

[8] Turkish melody type similar to G minor in Western music.

[9] Turkish melody type similar to C sharp in Western music.

[10] One of the main melody types of Turkish classical music.

[11] Main street, reserved for pedestrians.