My little sister was small when we visited our father in Peja. In Peja’s prison, which was filled with Albanian prisoners. Why do I know this? As a child, well I was quite little myself, I wasn’t going to school yet. I know because in front of the prison all the families that came to visit the prisoners gathered and had a bag in their hand {makes a move to describe the bag}.

[…] But these miseries that childhood carries will follow us throughout life because childhood [experiences] leave a trace. Luckily it did not fill me with hatred and I like that oblivion did not take over. I remember them because I never took them as personal, but I believe I share them with all the people who waited to visit theirs in prison. I share them with all the people who have been excommunicated, politically persecuted families, excommunicated by the society, a time when your neighbors did not pay you a visit because they were afraid.

The oral histories of women activists offer a unique space that gives visibility and permanence to a history of women’s subjectivity that has been consistently marginalized if not forgotten. Whether engaged in protests against the occupiers in the Second World War, the campaign to abolish the veil, the fight for girls literacy, the engagement in nationalist movements, the resistance against Milošević, and the fight for women’s rights across ethnic divisions, women tell vivid personal stories intersecting with the broader historical events of the time.

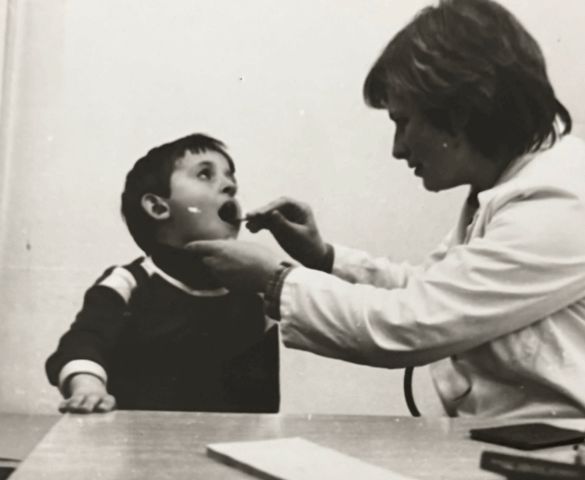

Flora Brovina

Poet/DoctorAlbertina Ajeti-Binaku

Architect…we had no tendency to give it a political connotation. It was more about giving it a humanitarian connotation, because families for days, with weeks have been under the siege. There was no free movement, you know to be able to go out and get supply, food and other things. And this was it. You know, we as mothers, as women who sympathize with mothers at that time in Drenica, who had no food for their children. […] And I remember that we were like, you know we were in a row and on the side we had police forces. Until we reached that point, then we were not allowed to go further. [Women] They wanted to negotiate, but they were not ready. So with an authoritative statement they ordered us, ‘You have to go back, otherwise we cannot risk, because then anything can happen to you and we cannot protect you…’

Fetije Kasemi

EducatorEvery year, we went to Macedonia, Ohrid, Dibra or any other place in order to see the language differences, because we speak differently from them, we spoke gegë there. In ‘72, çak [colloquial], it happened that we started to speak the standard language. It was difficult for us, more difficult for the students and even more difficult for the parents because of additions and suffixes…but they reacted to it, ‘Tell us, tell us how it should be.’ We had a hard time getting used to it, then it seemed all normal to us after a few years. Wherever I go for official visits, I still speak the standard language, I can’t speak the gegë.

Mihane Salihu – Bala

Civil Society ActivistMy family is a mixed family. My dad died Muslim and because he fasted during Ramadan he was unlisted from the party. Whilst my mom is an Albanian Jew. In our family we were brought up with all traditional religions. Most of us, kids, are baptized. So we are an interesting mix, I would say, of different cultures. Because in the end religion is something you do just for yourself and not for others. […] To grow up in an environment where your cousins have different religious belonging, and you have the possibility to make a different choice that is… It wasn’t well received at the time. […] I remember when we had different holidays, especially Eid Mubarak, the entire neighborhood made baklava, my mom also made baklava. Other holidays came, my mom prepared a more special food, but she was subtle, so it was interesting. What I remember are September’s feasts, the feast of baking bread and cooking wheat and grape and all that. That’s when it started getting interesting, ‘Ah the grandparents are coming…’ and it was interesting. It was later that we understood it was a different tradition.

Valdete Idrizi

Peace Activist‘Oh dad, how did you manage? You are ill and tired and you haven’t eaten.’ We saw it on the news. He said, ‘No, more’ he said, ‘my daughter, do you know that there are many like me? I was just one of them, just one of many people who were there. And no one can, when I told them…’ And he turned a little. ‘Never,’ he said, ‘the miners will never separate. And the underground,’ he said, ‘will move everything.’ He said, ‘Because we know, this is our treasure, this is…’ […] He would raise our morale. I will never forget what a feeling he gave me, and sometimes we didn’t need other explanations, as if, as if I understood everything just by looking into his eyes, without explaining anything further.

Maybe I was afraid to ask more questions, afraid that something would happen more, more awful. But what he projected, you know, that side of his that… ‘It was worth it,’ that’s how he put it. ‘It was too much bre, dad, it would not have mattered if you were not there. Everyone knew you were ill.’ ‘No,’ he said, ‘I could not but be with them.’ This is it. I know that every time [the anniversary] comes, because I don’t like to remember dates much, to remember the commemoration of this, of that… . But when I go, because I have been in the mine several times, I went to look for my father’s identification number there. His number was 618. I went to the tenth level, because I just wanted to know.

Suzana Gërvalla

Former Senior Officer at the MLGAThe doorbell rang. When I went to the door, a German neighbor, because we got along with the neighbors there, said, ‘Miss Gërvalla,’ she said, ‘come quickly,’ she said, ‘because this and this happened.’ She said, ‘They were shot,’ she said, ‘they…’ I went out dressed as I was at home. I went out quickly. When I got there, the door of the car was open. […] A body fell to the ground, it was Kadri [Zeka]. Jusuf was in the back. Kadri fell to the ground. […] When I went closer, I saw, because I did not know who is where, I saw the dead body, I realized it was Kadri. When Jusuf said, because…. He always called me çikë [girl], he knew me since I was çikë, a child, and çikë, çikë… ‘Çikë,’ he said, ‘I am here’. […] I said, ‘Ah, Jusuf, where, where is your…’ He said, ‘It’s in my stomach,’ he said, ‘and in my back.’ Since Jusuf was sitting in the back, he could move. He said, ‘But please, check on Bardh,’ he said, ‘is he alive?’ He said, ‘because I can’t hear him.’ He called, ‘Brother!’

The police stayed the entire time with us until half past one. At half past one another policeman came, he said, ‘Jusuf had surgery, he is doing better.’ We were happy. At least one of them. […] I phoned the Ambassador at the Albanian Embassy. I told him. The Embassy sent someone. At eight o’clock in the morning, Misin Mavraj came from Munich. With him, we got in the car and went to the hospital, because we had no other news. The police left, everyone left. […] ‘We came to inquire about Jusuf Gërvalla, this and that,’ he said. He immediately said to him, ‘He died.’ ‘No, no,’ he said, ‘three of them came in,’ he explained, ‘two of them died and the other…’ He said, he raised three fingers, ‘All three of them died,’ he said.

Sevime Gjinali

Musicologist/ ComposerMy father…. Look, at that time nobody was writing, doing musical notation, nor there were notebooks with scores. He was a rhapsodist himself, he wrote the lyrics and the music on the spot. But nobody notated them, there were no means to record them. […] And he decided about my education, that I become a musician, that I study music… at that time there weren’t, it was somewhat unusual for a woman to go to music school with a violin. The kids in the street threw rocks at us when they saw us, because I was going to music school carrying a violin….For a woman it was a bit unusual.

Lumturije (Lumka) Krasniqi

Accountant…a woman somewhere in the surrounding of Istog, her father had been killed, and she did not want to forgive, the family yes, but she didn’t want to, the case was terrible. Her name was [Besa], she gave her word, she gave the besa to her father to not forgive, to avenge his death. So, we went the next day but she did not forgive it. When I returned home I said to my father, ‘Dad,’ I said, ‘I want to ask you something.’ My father said, ‘What?’ I said, ‘I have a question,’ I said, ‘for example, God forbid someone killed you,’ I said, ‘and you asked me to avenge your blood, and I promised you to take out the blood, and now, the people asked me, for the sake of the Movement, to forgive your blood that I promised you to avenge, if I forgave it, what would you say? Were I to forgive it, or were I to keep my promise?’ He said, ‘When it concerns the national cause,’ he said, ‘never keep a personal promise. Personal promises are broken for the sake of the national cause. Everything,’ he said, ‘not just me, but if the whole family were killed, if the nation asked for it, if the national flag asked for it,’ he said, ‘not only forgive it, but give your life for it. So,’ he said, ‘this is my answer, for the national cause and the flag.’

So, more or less I was touched, I thought why that woman is not forgiving it, so the following week she already agreed, she agreed to forgive it and we went. Afterwards, after two weeks we went and she forgave the blood, but I remember the inner conflict of that woman, I will never forget, she, her braid. When she entered the room, we were crying more than she was crying. Terrible, terrible!

Hava Shala

Social WorkerThe beginnings of the Blood Feuds Reconciliation Movement.

The spokesperson of Milosevic’s government appeared on [prime time] news at that time […] And said, ‘They were not killed by our army and our police,’ by them, ‘primitive Albanians were killed because of blood feuds.’ […] It was very irritating, it was unacceptable to me, it was very discriminatory, it was very untrue, it was very dehumanizing.

And the next day I went to Peja. Myrvete was the first person I wanted to meet and the one I went there with the intention to meet […] I met her in Peja and we started talking, I don’t remember whether she had watched the news or not. Myrvete and I, we always understood each-other well, we were friends even before, before prison, during prison and after prison. And we understood each-other, we didn’t have to explain much, we didn’t have to put an effort to convince each other… she considered [blood feuds reconciliation] very important and she said, ‘Let’s see what we can do.’ […]

Brahim, Lul, Myrvete and I went to Adem’s [Grabovci] house that day, and we talked and we agreed without hesitation, I mean, we didn’t need to discuss much, we didn’t need to talk much or philosophize. […]

Then we thought about a person, a honourable, treasured and valuable face who also has the competence to enter the oda, to hold oda-style conversations, it was professor Zekerija Cana and professor Anton Çetta, Zekerija Cana first, respectively. He was honourable, at least to us, but not only to us, we knew his engagement, his writings.”

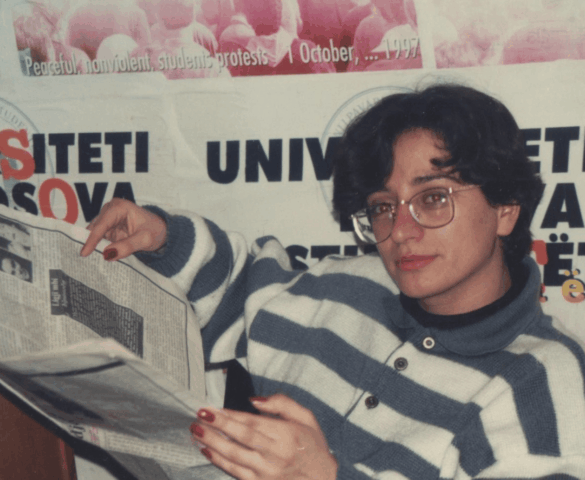

Zahrije Podrimqaku

Political ActivistIn that moment a colleague of the Council comes, he worked at the Council, he was quite old, Ismet, but I don’t recall his surname and he says, ‘I swear to God, you girl, Zahrije, the Council has been surrounded by police inspectors,’ continues, ‘and they are looking for a girl with curly hair.’ And I had my hair long, you know, up to here {shows the length of her hair}, I had my hair all curly, all… and I was young then, all different. There was no other girl with curly hair, except me (smiles). Right there, Ibra says to me, Ibrahim Makolli, ‘What business do they have with Zahrije? Zahrije has a low rank.’ Do you understand? They were not aware of who was being followed, what kind of assignments I undertook, and how I was being followed and how the police, for example, knew my movements well.

And they said, ‘If someone has to be taken away, I am the Secretary of the Council, Behgjet Shala, you are a member of the Chairmanship, bac Adem the director,’ he said, ‘they should take us with high ranks, they have no business with Zahrije.’ ‘So, Zahrije, have you eaten?’ I said, ‘No, I haven’t.’ ‘Come, there is a burek shop near the Council, let’s eat a burek.’ […] When we were out, they ambushed me, the inspectors came right to me and all of the sudden started searching me, thinking I have a weapon and that I am armed. I took out only my ID and they looked at it, and now Behgjet, they didn’t want to take him, for sure… Ibrahim Makolli and me, yes. But about Ibrahim Makolli, they thought he was Agron Ramadani. Because they [the police] through the phone… when Agron spoke with the Llausha Brigade, the phones were tapped.

On that moment, when Agron and I were taken, they put us in the car, closed the doors and called the main police station 92, he said, he spoke in Serbian but I understood right away, he said, ‘We arrested Zahrije and Agron Ramadani.’