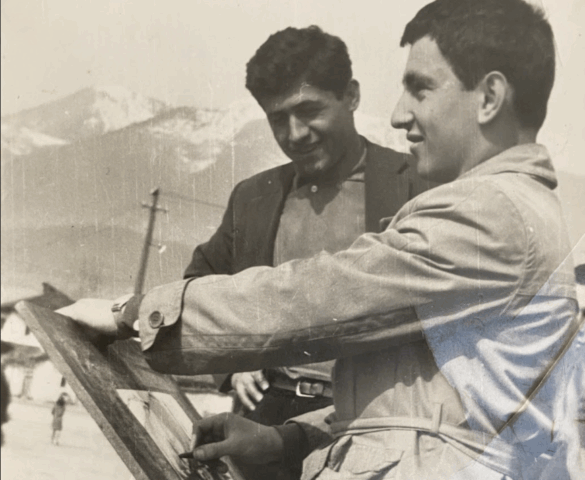

…when I went to elementary school, when I explained this to others, they wondered, ‘What is that?’ We called it tafte [board]. Tafte. It was an A4 plaque with a wooden frame, thin like a blackboard. On one side, it had no lines, on the other, it had lines to guide your handwriting. It had wide and narrow lines, wide and narrow. One side was empty, it was black entirely, and, on that side, we would do our in-class work and continue at home, written with white chalk that would scratch the surface, it would leave white or gray marks. And that was our school notebook, that was all we had, what was in our possession. […] The worst that could happen to you, while you were going to school, a friend, well, a malicious friend, would come from behind and erase your homework and you would have to go to school without homework.

This collection of oral history interviews documents the lives of artists and art professionals who worked in Kosovo and were active in the local art context during the 1970s and onwards. Over the following two decades, many steadily gained recognition within the broader Yugoslav art space. The political context that fostered the development of visual arts in this period came to symbolize Kosovo’s cultural golden age within Yugoslavia. It was a time of significant artistic and institutional growth, often regarded as foundational in the collective memory of cultural institutions. Notably, as part of these efforts to build cultural infrastructure, the Gallery of Arts in Pristina—now the National Gallery of Kosovo—was established in 1979, becoming the first institution to define how artworks were exhibited and presented to the public.

The oral history project with Kosovo’s modern visual artists was initiated in late 2016 by the Oral History Initiative, in collaboration with the National Gallery of Kosovo. In 2022, this collection of interviews has also been deposited for long-term preservation at the Arctic World Archive, Svalbard, Norway.

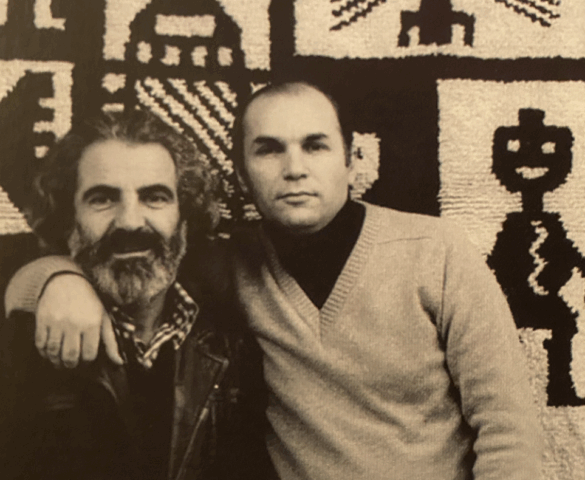

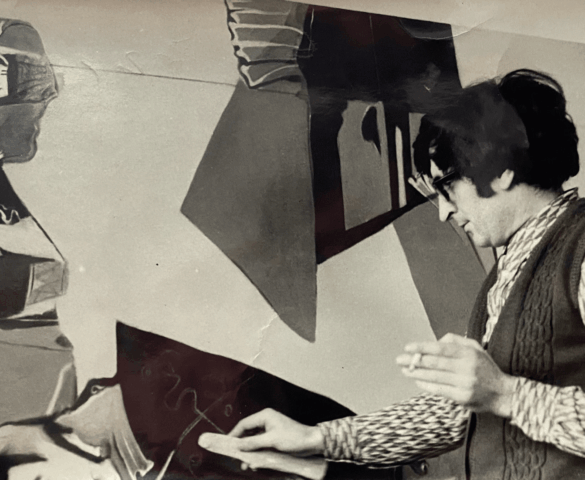

Fatmir Krypa

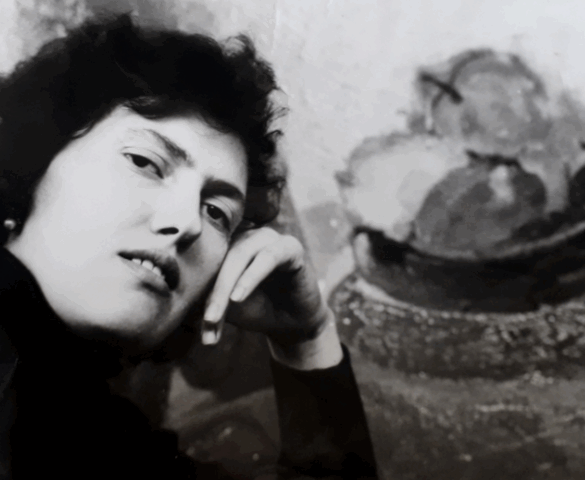

PrintmakerLirije Buliqi

Ceramic artistThe first day was… the exhibition space was really big. At the time, on the right side of the entrance, I remember this great hall. I wondered, ‘What takes place here?’ For example, when we received the artworks for the exhibition, we would prepare the documents to ship them. Of course, they went through the customs, but we used to have the customs service that would bring the artworks to the Gallery. So the customs procedures were simpler. Then, of course, we installed the works. We were a very small team of six and all of us would get involved in the exhibition production. […] There was the director Shyqri Nimani, Engjëll Berisha was the curator, we had an accountant, it was I, we had Rrahman the technician, and a cleaner. So, this was the core team with which we started. The Gallery was positioned so that, you know, we always had many visitors because the environment was such that it imposed it on you, people that went to the mall would drop by. Behind Boro Ramiz Youth Palace was the marketplace, and people that went to the market would come with their grocery bags directly to the Gallery. You know, we had a lot of visitors from all walks of life, not only artists. It was quite pleasurable, a great experience, something different for me. I liked meeting artists, I was young at the time and they were older and I didn’t even know most of them. They had to introduce them to me who is who, and for a long period of time I worked hard to know everyone.

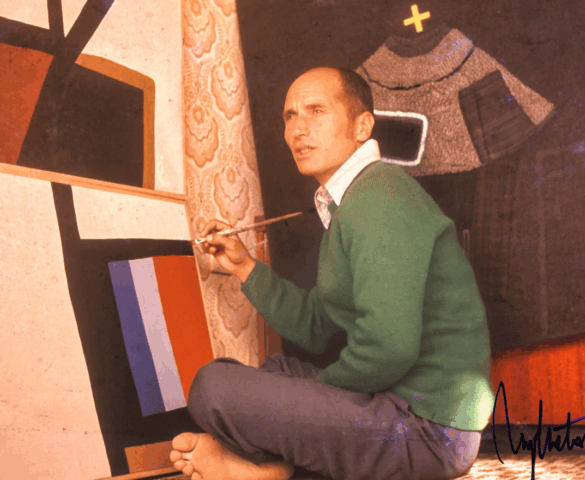

Xhevdet Xhafa

Painter…I had a preoccupation, how to understand living nature, the human figure, limbs, the physiognomy of the human head… I would walk around in Peja’s markets with a purse on my shoulders, some typewriting machine paper and some other helpful tools. I mostly went to the Green Market. From the villages on market days they would bring the agricultural products in some big baskets and small full of agricultural items.

Owners themselves were wearing traditional clothes, quite usual for the ‘50s, ‘60s. And I, quickly filled with joy, started drawing quickly that beautiful view. Then I often went to the bus station, it was more difficult for me to draw there because the travellers would always move. But, a little based on my memory and a little based on nature, the drawings I did were sort of croquis figures.

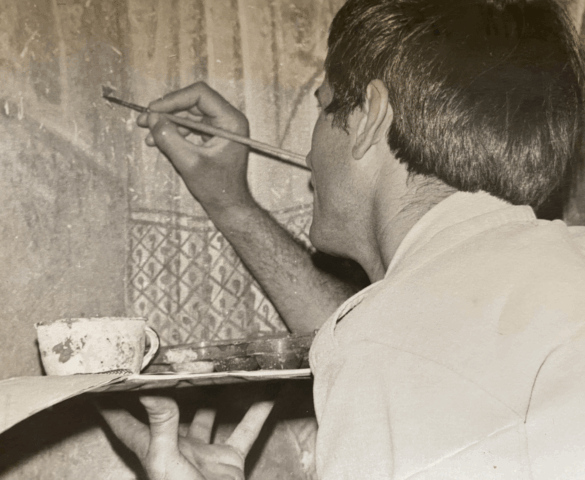

Hysni Krasniqi

PrintmakerI mostly find inspiration in nature. I take fragments from nature and try to live through them, live it with my heart and soul, and draw it on paper or paint it on canvas. For me that’s what’s important. […] For example, I have the Crops Cycle. Why crops? Crops because our people suffered from malnutrition, suffered from malnutrition. Then I have the Twig Bundles. What are the twig bundles? it’s a tool which our farmers always used, they used it to even the land […]

Then I have The Fireflies. What are the fireflies? The fireflies are the messengers of spring, the first sign that the crops are ready to harvest. Then this is how we knew that it’s the time of the harvest, and that’s what fireflies are to us. Like a fenix cik cik {onomatopoetic} sending out the message that somewhere the time has come to harvest. Like that. Then I have The Memory Flowers, the place I was born in, Llukar, though I spent more time in Pristina. The place I was born in is covered in flowers, snowdrops, violets. What wonderful smell violets have, it’s incredible, as if it were a perfume.

Alije Vokshi

PainterThis is the master who was driving his horse car and when I saw him, I stopped him and said, ‘Can you come to my atelier so I can make a portrait of you?’ ‘Yes,’ he said. And I worked, and these hands, I mean he is tired, and his plis, the color of his plis is not pure white, but I did it like this because he had worked and he is tired, and the color is like that because of the dust. And when Jusuf Kelmendi saw this in my exhibition, he said, ‘You can see it in this painting, these hands, tired… a really, really good portrait.’

Shyqri Nimani

Graphic DesignerThe Academy was a very good one with professors who had studied abroad, I mean in Prague, Munich, Paris and who had collected a lot of knowledge in those cities and brought it to their own places, especially in Belgrade, Zagreb and Ljubljana. And the influence was easily noticeable also to a high number of painters from Kosovo who had studied in Belgrade, Zagreb and Ljubljana, I have to mention that they were influenced by those professors who were influenced by their studies in the European cities that I mentioned. And in the beginning of the careers of these artists from Kosovo you could see the influence of their professors. And this is very normal because it is thought that since the thirteenth century Giotto had this influence as well. Then Leonardo had someone, as well as Michelangelo and Picasso, but in the meantime they got rid of those [influences] and created their own doctrine. The ones who remain under the influence of someone else will be lost, right?

Rexhep Ferri

PainterTajar Zavalani translated that [Mother by Maxim Gorky], he understood what communism is and left, then he worked at Radio London. My mother would listen to it a lot, ‘Communism will end today, tomorrow.’ One is inclined to go from one extreme to the other. When we returned to Gjakova… our property was confiscated and my dad, dad, dad did not, he left, he never… he thought that he would be safe in Gjakova, that he would not have to leave his family. From Fadil Hoxha to Sahit Bakalli, they were his schoolmates and worked together as teachers in the Gjakova Highlands.

We met with Sahit Bakalli, before meeting him… and Sahit Bakalli said to him, ‘Look Shaban, you cannot spend the night in Gjakova. We cannot protect you from Serbs and Montenegrins, you are the heir of Jakup Ferri, Hasan Ferri, the brother of Riza Ferri, Shemsi Ferri that have led the war against the partisans, and you also were with them. You have to leave and go to Albania, in Tropoja, where you used to teach, where your in-laws are. This tempest will pass and you’ll be alright somehow.’ He followed him out of the town, my dad left and we stayed.

[…] sometimes when you are lonely, alone, if one person knows two words in Albanian, you think it’s your brother. He would call my mother sister and she would call him brother, and they weren’t even from the same village or city, but from the Gjakova Highlands. Pashkë, Uncle Peshk [Fish] I would call him. He was unlettered, but he smoked like an aristocrat – it seemed to me that way then – with a pipe. My mother sent to him the clothes that she made with the loom to sell and he sent her off with a couple of lies, ‘Ms. Hatixhe, I heard on Radio London yesterday night that a week will not pass and communism will end.’ And that lie would amuse my mother for a week. Next Monday, he would lie to her again, and the years passed, we grew up.