Part One

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Mister Xhafa, can you tell us about your early memories, the rreth you grew up in and your family?

Xhevdet Xhafa: Yes. As soon as I started speaking, growing up, I started drawing. I remember it well, the great spring of 1941, Second World War. As we know, former Yugoslavia was defeated by Germany. With the defeat of former Yugoslavia, half of the Albanian lands were liberated from the almost 30-year Serbian—Slavic occupation. I remember there was a big party in Peja; the Albanian language education started. Tens of teachers came from what we know today as Albania to help with Albanian education in Kosovo, in the liberated land.

I was in the first grade, there were many students in the class, each one of us had two notebooks. I loved drawing very much. Before starting learning in school, I used to draw on the walls of the neighborhood. And I started drawing in these two respective notebooks as well. One day my teacher said, “These notebooks are for writing.” I said, “I love drawing.” “Alright, I can allow you to write on the first sheet of the page and draw on the second one.” I listened to him and did as he advised. But the marks of the pen could be seen even on the first sheet of the page.

My teacher was silent… two, three days after I entered the classroom, he came right to my desk, brought three notebooks with him and said, “Boy, listen, I have brought you three notebooks, two of them are for writing, you cannot draw on these two, and the third one without lines is for drawing, you can draw on it.” And I was very happy, I started drawing in the notebook without lines, I drew everything that surrounded me. I loved drawing domesticated animals mostly; they were near me. Every family, every lagje and every town had one, two, or three domesticated animals because the social conditions of the people were very difficult… those difficult social conditions were experienced by my family too.

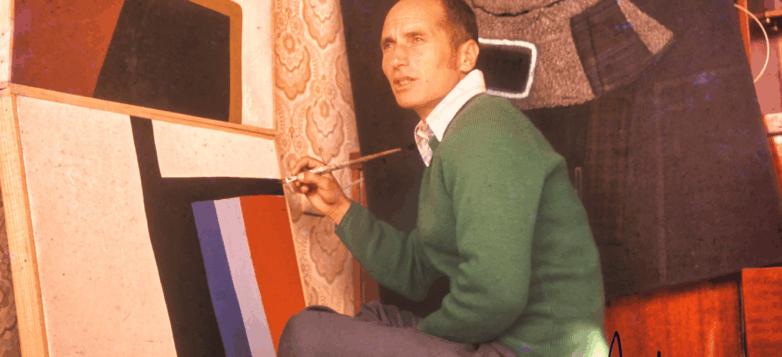

But as the time passed, that liberation of the Albanians didn’t have a long life. The new Yugoslavia was created, a shop was opened in Peja, Knjižara was written in big letters. I bought a drawing block, on the first page of which was written Blok broj jedan [Drawing Block, number one]. I mean it was after the war and I say, some say, after the liberation, but I don’t agree with that thought. I bought a drawing block and some watercolors with a small brush, I started painting everything that surrounded me. I started going out in the neighborhood and painted some old small houses, some big wooden doors, then I also went out in nature. In Peja we have a hill that is called Tabje, it is beautiful during the whole year, nature makes it beautiful. Then I went and drew Rugova Canyon, the Patriarchate of Peja as a religious building… and some other buildings.

But I had a preoccupation, how to understand living nature, the human figure, limbs, the physiognomy of the human head… I would walk around in Peja’s markets with a purse on my shoulders, some typewriting machine paper and some other helpful tools. I mostly went to the Green Market. From the villages on market days they would bring the agricultural products in some big baskets and small full of agricultural items.

Owners themselves were wearing traditional clothes quite usual for the ‘50s, ‘60s. And I, quickly filled with joy started drawing that beautiful view. Then I often went to the bus station, it was more difficult for me to draw there because the travellers would always move. But, a little based on my memory and a little based on nature, the drawings I did were a sort of croquis figures.

I felt a lot better when I went to the train station; I went there during winter, summer, rain and snow and I usually found the travelers waiting long hours for the train, tired travellers, I saw them in crowds lying in various positions. To me it was attractive, every position of the travelers, very close to be drawn… and so for six, seven years of my work, I welcomed every free activity. Not only did I understand living nature, the human figure, limbs, but I gained the courage of expression, the honest, natural courage, without using the stimulating stimulants which were and are still used by several artists.

I was always restless as an artist… I started learning about the history of the Albanian nation through living memory, those thoughts inspired me. I thought about how to understand and get along with the humans, with myself, to help this with art, not to allow myself to remain a slave to color but a slave to myself, to the humans of this land. I started being inspired by those closest to me, by the autochthonous architecture, especially that of Dukagjin, I am talking about Dukagjin because I was born and raised in Dukagjin.

I often went to visit various architecture in various cities, I mostly went to Gjakova because there was a more or less isolated architecture, but with artistic values, the architecture of Gjakova is directly connected to the environment, humans, nature. I also went to Prizren, the architecture there is less autochthonous, as we know Prizren was a bridge that connected the nations of Balkans, it was normal that its culture was interrupted by some other cultures, but those cultures were injected into the local architecture. And so even today, the architecture of Prizren is amazing, it is directly connected to nature, people, humans.

I was always in a kind of depression. Then we had more valuable architecture, with a longer life, those are the kulla of Dukagjin, for example the kulla of Strellc, Lubeniq, Isniq and many other buildings where Albanians used to and still live and that are very valuable artistically. If we draw a man with traditional clothes next to the kulla of Dukagjin, we will see that these two physiognomies unite, we will have one single physiognomy… then I was inspired and I used the rich and honest folklore that we have; as we know the Albanian folklore has for centuries been transmitted from generation to another.

The layers, decorations that were embroidered in the traditional clothes were done so by healthy, honest human minds; in these layers, as we know, the black color dominates, this color is directly connected to the physiognomy of the Albanian nation, it is a convincing, strong, traditional color. I started dealing with sports as well but I didn’t feel good with myself, I was restless… when I was dealing with gymnastics, more with running (coughs), my favorite path to run was the one in Rugova Canyon. I would run slower on the uphill part of this path, while much faster on my way back down; my legs would move themselves downhill.

While going to and returning from this path, I always had my mind and my eyes directed towards the cliffs of the Rugova Canyon, such a splendor could only be created by nature and left to us. I took something from those cliffs and showed it in my works. Nature helped me to get engaged in art, it led me to love art. I easily expressed my preoccupations with the tools I had close to myself, I had them in my surroundings… I lived with them, I know their physiognomy very well and I expressed my feelings, my concerns directly through those tools. I have tried to give a biographical glimpse of my artistic activity through words. Thank you!

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Mister Xhafa, can you tell us where did you first engage, the first formal steps that were… where did you get the education, did the Shkolla e Artit in Peja exist at the time?

Xhevdet Xhafa: Yes, the Shkolla e Artit existed in Peja, it was established in 1948. I was the fifth generation, the Shkolla e Artit was very strict, it was even the second best school in former Yugoslavia when there were around seven or eight middle schools. I mean, there was the Shkolla e Artit where we all learned, not as much from the professors as from nature. Nature inspired us to say things honestly, to express our knowledge on the canvas.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: What kind of visual school was it, at that time?

Xhevdet Xhafa: It was not much of a painting school, there, the arts were a little limited, but it was strong, many generations have graduated from it and today they are among the famous names that represent the Kosovo arts. It was more or less, if we compare it to current schools, a classical school, but it was a strong one, sustainable. I took my first steps there, then since the education there was a little limited, nature was present… I had, I was a little old, I had the power to do something more but we had no courage. I went to Ljubljana for my studies, I happened to have a good professor, Gabrijel Stupica, who at the time was considered an academic painter, this is what he was considered by Italians.

And I started getting comfortable to express what I knew, the professor was surprised, he would say, “Good, good, good!” They provoked me once when they said, “Can you show nature the way it is?” I said, “Yes.” And when I did so that is when he left me to work, they didn’t interrupt me at all. Because they knew I had an artistic sensibility, I loved art and so I started being courageous to go on and so I started with my works. Only later did I show up with my paintings, I was withdrawn, limited, because I lacked the courage to show my opinions.

But, many critics came from former Yugoslavia to see what was happening in Kosovo and when they came to me they would say, “Good, good, good!” So the courage in me started strengthening. I never (coughs) was part of any competition, they invited me to exhibitions be it biennials or triennials in former Yugoslavia. But also when exhibitions took place abroad, organized by the Zagreb or Ljubljana museum I was invited. I saw there or someone told me that the newspapers wrote and they distinguished me, three, four, five, ten people and I among them, so this is how I started getting more courageous.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Mister Xhafa, how did you go to Ljubljana at that time, I mean who encouraged you, who supported you to go to Ljubljana. Can you tell us what kind of art did they teach you there?

Xhevdet Xhafa: I decided to go to Ljubljana, I didn’t even attempt to apply in Belgrade, my friends always went to Belgrade, some had success and some others not. I went to Ljubljana with the aim to as rarely as possible return to my homeland (laughs), to be present, to work, to give everything from myself, I don’t know, my abilities and I came to such point that they valued it. There was one moment when the rectorate took four or five of my works in order for them to be seen by whoever would come, for the guests to see a pure art. It is my opinion and I still say that nowadays honest art is valued, the new works as well but also the honest ones, and the value of being present is understood.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: What about when modernism became famous in painting, I mean did they ask you to make socio—realist paintings in the Shkolla e Artit in Peja or what kind of art genres?

Xhevdet Xhafa: The Shkolla e Artit in Peja was a classical one, it was the nature of describing nature, they wouldn’t allow you to do anything else, and I had the will since I was a little older to say something more. One moment I started saying something, what I thought was right, but they didn’t allow me. When I went to Ljubljana I was met with understanding, they supported me. Modernism had started long ago, one century ago but…

Erëmirë Krasniqi: In Kosovo?

Xhevdet Xhafa: In Kosovo? What do I say, it started, I say, maybe with me a little (laughs), and age should be taken into consideration as well. I mostly started becoming courageous in expression, seeing that my art was needed and valued. And I was part of the biennials and triennials that were organized, I was highly valued, then also in Cagnes—sur—Mer there was an international exhibition where 42—43 states participated, and I was awarded the national merit… for example, in the Yugoslavian Contemporary Arts, there were only two of us who were specified, a Croatian and I.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: How did they describe your work?

Xhevdet Xhafa: A pure, autochthonous art with national value.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Of Yugoslavia or…?

Xhevdet Xhafa: Of Yugoslavia and abroad, these were the views of the internationals, the critique that… for example to be honest, the art of Yugoslavia doesn’t have such a value in the current world, they even call it a province. But, a critic from Australia wrote in the newspaper, “The works of Xhafa, can go beyond borders, and of this and that…” he mentioned three or four of us.