Part Four

Rexhep Ferri: The Demonstrations were brought here. But even us as professors helped because my generation had an urge to go to war with Serbs, to go to war with a strong enemy. We were aware of how many wars we had lost, and our students, being given a freedom in Kosovo to open schools to develop culturally. We were connected, if we talk about visual arts only, we were connected to Belgrade, because the professors at the Shkolla e Mesme e Artit were from Belgrade, most of them. And we, they finished school, they finished school, they were children of aristocrats who had finished school in Paris too. So it wasn’t very hard to go from a province to a capital city, because for us in the Balkans at the time, the only one [city] that we didn’t know but it was like a European capital city [to us], was Belgrade, and Zagreb as well.

Maybe it was difficult, but it wasn’t that difficult to adapt. We were more poor than others, but that wasn’t noticeable in the friendships because there is a lot of solidarity among young people. So, I never felt [like I was] of another nationality among people with other nationalities, but we were all together as if we grew up in the same neighborhood. I have studied and specialized for eight years in Belgrade, because the Academy [of Art] lasted five years, a semester to get the diploma, then the second degree lasted two years and a semester to get the diploma, so it was seven, eight years in total. So, during those eight years, no one has said even one bad word to me in a national sense, no one offended me in a national sense. Maybe because it was the time of those professors and colleagues of mine, my classmates who weren’t biased because even school after [the Second World] War in Yugoslavia was oriented towards Europeanization, not towards churches and Byzantium. So, we felt the same, like me, like them, we dreamed of Paris.

I remember once when the son of the housekeeper of the Academy, because the Academy had its own housekeeper, their apartment [was] next to the Academy, they would clean, there was a café there, and their son once went, he was a driver for some French embassy, he went to Paris and we all gathered to listen to his stories of Paris. Who were we asking, a driver who didn’t know, with high school education, I don’t know what kind of school he finished.

But I remember something he said that turned out to be true, he said, “Everybody works in Paris, not in their profession, they work something else. Someone who studied geography, works as a gatekeeper.” I don’t know if you understand me. He is, he was a driver, he cleaned the streets, and so on. So, no one does their job. This was what he had seen, he also went and visited the Louvre [Museum] so he could tell us about it. But now, since I’m talking about the Louvre, we all dreamed about it. I couldn’t go there during my studies for two reasons: I didn’t have a passport and I studied for eight years without a scholarship, since my family was not on the partisan side for reasons connected to our family’s history.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Was this one of the reasons you didn’t have a passport?

Rexhep Ferri: Huh?

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Was this also one of the reasons you didn’t have a passport?

Rexhep Ferri: Yes, I was registered in Albania, because I was born in Albania. So, my mother and I were Albanian citizens. So, then when I, I’ll talk about Belgrade. In the beginning, in Belgrade, it was a little hard for me to adapt. There was a professor who helped me in the beginning, who was a professor in Peja and he went to Belgrade.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Which one was it?

Rexhep Ferri: Miša Đorđević. And he started working at Television Belgrade, back then there weren’t, Television needed commercials and all commercials were done by hand, they were drawn. From letters to every other visual message, and Miša would take me with him to help, to make the signs, to enlarge the sketches, to make his sketches and so on. So, I started doing what I did with the store signage in Peja. I started to work in Belgrade in a quite difficult job, but I sacrificed my free time to make a living.

I have always been modest, I did not pursue luxurious things, I would get enough money to pay for the dorm or a small apartment. I remember I had a room once, I had for two, three or four years. It was two by three meters and it was the room of my youth, the best room of my life (smiles). That’s how big Jakup’s room is, but he left the room now, now he has the entire floor upstairs. In Belgrade, since I was a fan of literature and I spoke Serbian, I started to read but not write.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: How did you learn Serbian? If you could include that.

Rexhep Ferri: High school was in Serbian, five years.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Did you have any problems at first?

Rexhep Ferri: Well, I had to learn it. There I started reading the great world writers, we didn’t know them here and we didn’t have them. I have, it was a huge difference, but youngsters learn fast, faster than maybe, I don’t know if hearing or sight is faster, but I think sight. The youngster’s sight catches things maybe much faster than [their] hearing can. I saw Beckett’s plays in Belgrade, in Pristina they were still showing Kryet e hudrës [Garlic’s head], a drama, useless words, or the one by Kristo Floqi, Kushërini nga Amerika [The cousin from America], how a cousin came from America and they all went to look at what he brought home. So, but Kosovo started very quickly, every time I came home from my studies I saw a…

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Development?

Rexhep Ferri: A development. For example, in Pristina it happened to me, I was friends with writers, I went to a coffee shop, that was Army’s coffee shop next to the Grand [Hotel], at the house that…

Kaltrina Krasniqi: Kino Armata?

Rexhep Ferri: At Armata, there was a coffee shop and they didn’t let me in, they didn’t let me in, I was with two journalists from Rilindja, they didn’t let me in because I had long hair (laughs). It became a huge deal. The next day, the officer comes to apologize and so on. It was (laughs) humorous, you know. So everything arrived [in Kosovo] quickly, the wind brought things faster than people think. And apart from following international art…

Erëmirë Krasniqi: What kind of exhibitions would be on display there? Can you…

Rexhep Ferri: In Belgrade, before me, there was Henry Moore’s exhibition in Belgrade. In 1951 was Henry Moore’s exhibition in Belgrade. In Belgrade, I saw the exhibition of America’s modern art, an American art collection. When pop art was trendy and for me seeing pop art was new, and there was a jacket of an American soldier of the Vietnam war and it had a pocket. A Belgrade citizen had the newspaper Politika with him, and he put it in that pocket. But I would go to see exhibitions like that two or three times and, like you [addresses the interviewer], I always took a pen and notebook, I would take notes or something. When I went the next day, I saw Politika in its pocket…

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Someone had intervened (laughs).

Rexhep Ferri: Someone had intervened. So, there were a few reactions from those who were under the umbrella of socialist realism, because they…. But, Tito’s politics separated art from socialist realism, it wasn’t easy then. There were reactions, there are no restrictions in art but I concentrated more on painting then, not literature.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Did you study painting or graphic arts?

Rexhep Ferri: No, no, painting. Not literature because the word is read and it could be misunderstood, a word could slip, and then it’s read, understood, and it costs you politically if you have a question mark somewhere. But, even as a student, I started to present in exhibits, in Belgrade and out of it. No only me, but to be honest before there were other students there, Muslim Mulliqi, Gjelosh Gjokaj, Matej Rodiqi, Shemsedin Kasapolli.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: He taught at the Shkolla e Mesme e Artit then.

Rexhep Ferri: Yes, he was my professor in Peja. These were the first generation of Albanians who studied, and some others that I can’t remember, there were a couple more. We are the second generation, me, Tahir Emra, Xhevdet Xhafa, Daut Berisha, Fatmir Krypa, and many others. Until we had the means to open one in Pristina. The first building of the University of Prishtina was Shkolla e Lartë Pedagogjike, and there was the section of arts and thanks to Muslim Mulliqi, it was a great arts school. And there were still students who came from the Shkolla e Mesme e Artit in Peja with good figurative culture, during the time I was there as a professor, I got to the point where I would rather accept someone who finished the gymnasium rather than the Shkolla e Mesme e Artit. The Shkolla e Mesme e Artit had gone from one end to the other. Maybe it isn’t the professors’ or students’ fault, but of those who make the standards for how to profile a school. They made it like a craft school. I don’t know how far it got, but at that time, I noticed that it was too far gone and I didn’t know where it would end up.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Can you tell us more about Shkolla e Lartë? How was it established?

Rexhep Ferri: But, if it weren’t for that school, because the Shkolla e Mesme e Artit was opened in 1949, I studied there in ‘54, the fifth generation. If that school was not on the level it was, with those professors, none of us, starting from Muslim Mullqi to me, we wouldn’t be who we are.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: You couldn’t even have continued your education further, since that…

Rexhep Ferri: We would have gone somewhere else, physics or chemistry, something would’ve happened. And I’m very grateful to the professors who had that culture and weren’t egoistical about keeping the knowledge for themselves, but they loved us like themselves, even though most of them were Serbs and Montenegrins, they loved us Albanians the same. During my studies, because I did my figurative studies in Peja, I started learning there and never stopped. I am still a student, I am still learning. Up to the point that I am strong and capable of opening a book or a new catalog to see how someone young is painting, what they’re painting, so I’m still some kind of a student that is learning something. And I would want there to be more provocations from the new generation because I would feel young also. But the new generation, I don’t know how to explain the new generation.

While I was in Belgrade, I would take a magazine by the American Embassy Pregled [Review], it was published in Serbo-Croatian once a month, it was about culture, and there was an interview with an American painter, a young painter who textually said, “Picasso created 50 masterpieces within 60 or 70 years, or 30 masterpieces, but I’m thinking of to create 30 masterpieces in three years.” Look, I don’t know if this would work, with what kind of machine can you do that, you can’t go to the Moon or anywhere else in three years to make 30 masterpieces, and he was serious, he was in the younger generation.

And I feel like something similar exists in today’s generation. Maybe, maybe because you have figured life out much quicker, as something amazing, with one thousand flavors and that passes by fast, and since it’s like that you have to take advantage of it in every way, in every pore. I don’t know, we were a generation who was devoted to our profession, without the spirit of materialism, without the spirit of treachery, but we believed in what we worked for, but a person believes in their work if they believe in themselves. If you don’t believe in yourself, you can’t believe in your work. This was the generation that I would not want this myth to be over with us.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: When did you come back from Belgrade?

Rexhep Ferri: Excuse me?

Erëmirë Krasniqi: When did you come back from Belgrade? In which year?

Rexhep Ferri: I came back, I came back from Belgrade after Paris in ‘67, in 1967, I finished the Academy, I went to Paris, I came back from Paris to Pristina, I worked at Rilindja as an arts editor for two years. I would also be part of exhibits in Belgrade because I was accepted into the Association of Figurative Artists of Yugoslavia. Not just me, others too, Muslim and others who were here. Then, I started my third-level education in Belgrade, those two years while working at Rilindja I was still undecided, do I stay in Pristina or go to Paris, and I found a medium and went back to Belgrade, but during those two years, I wasn’t a citizen of Belgrade. I went there for a day or two, but I wasn’t there all the time.

A very big change happened in Belgrade, a big change happened in Belgrade and I saw that the behaviors aren’t the same as those of my friends, for example, women were more thoughtful, they always brought us something. Actually, one of the years we had such a great time. The wife of one of the ambassadors of Iraq or Iran, I don’t know, one of these countries, they would bring her with a car. That was the first car that stopped in front of the Academy and she would bring us a jar or jam or something. We would go to the bakery there and would buy bread and she would take care of breakfast. So…

Erëmirë Krasniqi: How did that behavior change?

Rexhep Ferri: And… I’ll illustrate a change. There was a girl from Belgrade, a classmate, we called her Pegi, because she had freckles (laughs) and, “Come on,” she would say, “Ferri, let’s go drink some hot raki at the bar.” And before we got in, she would give me the money because she wanted to show them that she is going in with a gentleman, not with a person who doesn’t have money, and she wouldn’t go in alone. She wanted to go, but she didn’t want to go alone. After two years, within two years, a change happened, I can’t call it emancipation because it wasn’t, it’s something beyond emancipation. What’s beyond emancipation? Maybe a full stop and a dash and a full stop again.

I found an academy where anyone could go in, anyone could go out. It wasn’t the same dedication as before. It wasn’t the same dedication because this was said to me by my professor when I went for my third-level studies, “Do you think it’s them?” After I finished my studies, I met him because I became a professor here, “How is it going with your students?” He asked me. He said, “Do you think that my students are like you used to be? Things have changed.”

So, it’s good if things change for good, but it’s twice as bad for those nations who have taken the step of forming a national identity late, cultural uplift, cultural representation. Because there are people who have put their history into a drawer and into museums, and we needed to say that we have finished school, we needed to present ourselves.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: How did these fast steps affect you?

Rexhep Ferri: They arrived here slower and at that time, to be honest, not with a critical intention, but Kosovo was known in the Yugolav art space, in Yugoslavia, which had 22 million up to Ljubljana and in the exhibitions in the world where Yugoslavia would present, visual art was the only popular art in Yugoslavia, more than literature, music, film…

Erëmirë Krasniqi: They started late.

Rexhep Ferri: Late, even though even in these fields there were some good works. In music, there was Rexho Mulliqi, Nexhmije Pagarusha’s husband, he popularized Nexhmije Pagarusha, he was a genius, an unfortunate composer who didn’t fully realize his potential as much as he could have, but he was a genius. There was Muharrem Qena for drama. His Erveheja that got all the prizes in Belgrade. This started too, not only visual arts, but also…

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Dramatic arts.

Rexhep Ferri: I was in a concert in Belgrade when Nexhmije, I was a student, the hall was full of people. I went because we were friends, but also, how blood works, it’s strange, it’s also something good. I also went because she was Albanian, I was proud of her. Seeing Bekim Fehmiu in a theater play, Albanians from Kosovo and Albanians in general owe a lot to Bekim Fehmiu. We owe him because with our professionalism and our ego, I’m not helping him because I want to do it, we don’t have him in any of our movies, in any sentence in Albanian movies, Bekim Fehmiu isn’t present, it’s our fault even though he wasn’t a calculating person, he didn’t give up. But people who are devoted to their personality, they don’t give up, they don’t beg, they don’t beg for anything. You have to talk to them nicely like mothers talk to their children, and so it’s a big lack.

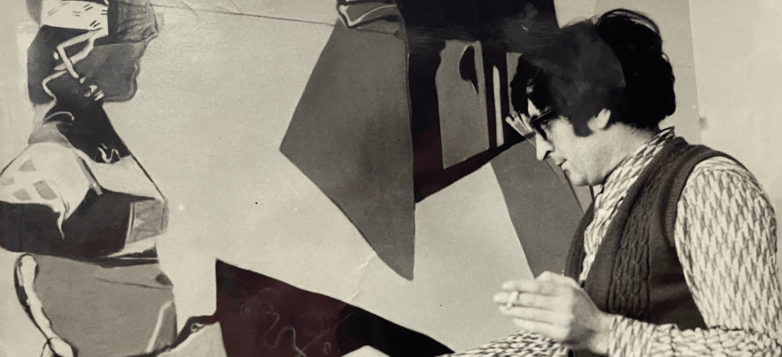

I remember an exhibit of mine in Belgrade, since we’re talking about Bekim Fehmiu, in one of my exhibits in Belgrade, I went to the opening and when I went to the opening the next day Ali Shkuriu passes by and sees it, because it was in Palace Albania, there was the Cultural Center Gallery and the advertisement was outside. A high political official came in, I’m not mentioning his name because it’s not worth it, and he asked why I didn’t send him an invitation to the opening. I apologized because I came by train and didn’t know where they sent the invitations. They were used to other painters that sent them [invitations], but I didn’t have those close relations with them, but we weren’t on bad terms either. Bekim was also there, we were hanging out with Bekim.

The next day, he invited us to his house to drink whiskey with him. Bekim apologized, he said, “I apologize but…” Bekim didn’t like him either, I don’t want to mention his name because there were only two other people, I can’t say that they have done any dirty national work, they made some kind national ploys, for the other, but two of them, one of them was this one. Bekim apologized and said, “I’m going to go to Italy,” he was playing Odysseus, Ulysses. He went home and he said, “Come on,” he said, “Rexhep, don’t bother with him,” (smiles) he said, “Bekim will buy you a whiskey. Now we will drink whiskey, we don’t need to go to his house.” It was true, and this is how it ended.

Most of the people who were in high functions tried, it was a very difficult time, they tried to protect their people, Albanians, they tried to protect their personality also. I don’t want to mention names, but there were two, three, people whose ego to build a career made them more Catholic than the Pope.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Were there political interferences in art? You mentioned it a little in literature.

Rexhep Ferri: There weren’t any in painting, in music, because music is abstract by nature. But there was in literature. Those who studied Albanology and literature, their parents would say, “Do you want to study the school of prison?” So this is how it was at that time.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: They would scan everything that was produced, published? I mean were there specialist people who read if there’s any subtext? What happened?

Rexhep Ferri: Look, knowledgeable people, those who know, don’t make mistakes. I had a worker while I was building my house and the workman said to him, “O, Halim, like a dynamite,” he was opening the foundation with a jackhammer, bam, bam {moves his hands up and down}. I put this figure in my poetry, but they removed it.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: How was it interpreted?

Rexhep Ferri: Because knowledgeable people didn’t interpret it, but ignorant people did, “Rexhep is asking for the dynamite.” Just like Ilir Shaqiri’s song about homeland, what does he ask about?

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Oh, give me back what you owe me (laughs).

Rexhep Ferri: Give me back what you owe me or something like this. In Albania they said, “What do we owe him?”

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Yes. (laughs)

Rexhep Ferri: So, it was a time when… now, let’s leave Belgrade behind, even though like all of us during our youth, the best part of our life, the best years, I was there, with all the difficulties that we had, all the difficulties a devoted student could have. We had to be devoted, it didn’t work otherwise. Still those are the best years, as hard as they are {points to the interviewer}, these are your best years.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: (laughs)

Rexhep Ferri: In Pristina, when we just started to walk on our own feet and thanks to our communist leaders, not neo-communists because they’re worse, we still have neo-communists in Tirana and Pristina, who swear on Lenin’s, Stalin’s and Enver Hoxha’s head. But anyway, let’s not talk about politics, we never got anything good out of it.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: But there was help from the socialist system to create cultural infrastructure, right?

Rexhep Ferri: But, but the need of our leaders to be equal to other republics of Yugoslavia helped Albanian culture. When you went to the offices in other centers, you would see their best painters, Serbs in Belgrade, Croats in Croatia, Slovenians in Slovenia, and there they also started to not take their son’s, aunt’s painting, but they would take… today, there’s aren’t any paintings by Muslim Mulliqi in any office. I’m taking Muslim as an example, they started to buy paintings, they starting to bring paintings for the Modern Art Museum, because all the republics had a Modern Art Museum, only we didn’t.