Part Four

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Do you remember ‘89 or ‘90, when you were fired?

Hysni Krasniqi: Yes, I remember very well.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Can you tell us how it happened?

Hysni Krasniqi: I was fired on the date 13, 1989, something like that, I have written down. When they fired me, I didn’t want to leave, “Why should I leave, you didn’t hire me,” I said, “You didn’t hire me, we know who hired me, not you.” Kradrush Rama and I stayed there and they brought a cleaning lady. She cleaned the rooms of professors, students, and she said, “Professor, sign here,” I said, “Sign what?” And I said in Serbian, “Idi uzmi metlu i čisti.” Take the broom and clean, get out of there. And she left. I went to the professor’s classroom and a postman came, he was Albanian, “Professor?” “Yes?” He said, “You have to sign.” I said, “Sign what?” I said, “Go deliver mail, this doesn’t concern you sir. I will not sign it.”

Now another one comes, he used to be my student, sculptor Zoran Karalejić. I called him Kërle, meaning “stump.” He said, “Profesore, treba da potpišete” [Srb.: Professor, you have to sign]. I said, “I will never sign it. Is it clear? Firstly, I don’t understand what it is.” “You don’t understand?” “Yes.” They take our former secretary, Ballata. They wrote it in Albanian, they translated it to Albanian. I said, “Ballata, look at the state you’re in. You’re selling yourself for five marka. I will not sign it!” I said, “Do you not know me at all?” I will not sign it.” I went home, then came back there with Kadrush, the police came, five or six men with guns and they tooks us out by force. We left. What could we do? I didn’t sign it. They brought it to my apartment to sign, I still have it, without a signature. This is how it was, I swear.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: What was the beginning of the Faculty of Arts like, if you can tell us…

Hysni Krasniqi: So the Faculty was organized, we had the rector Ejup Statovci, the only one in the university, our faculty, the only one in the university that worked with the Republic of Kosovo, with the rule of the Republic of Kosovo. Enver Statovci, I mean…

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Ejup.

Hysni Krasniqi: Ejup Statovci, Ejup Statovci said that we have to find a solution. We made a solution, each one of us worked in our own studios. I had my studio in my apartment, in a corner. I worked there, we took our students there. With my own supplies, my own paper, colors, oil, my own heating, my own lighting, no one gave me any money, I didn’t even ask. I worked there for four years. I have three certificates of achievement, the secretary didn’t give one to me, he was arrogant, but it’s no problem. When the students used to come, first when they came, I told them, “Don’t come too many at once, not in groups like that, but come one by one and don’t tell people where you’re going. We’re going to my brother’s, two or three people. That is how they came.

There was a huge hallway there, so I made a big desk. So those who came early wouldn’t be cold, it was warm, they all sat there. When they all got together, I opened the door, they came in and worked like they were in the Academy. They worked there, I gave them everything, materials, I had textbooks, I feel bad saying this but the students also took some of my books (laughs). They didn’t take anything else, they liked books. Anyway, we worked there all the time. I worked twice a day, in the morning and evening. Why? Because there were too many groups, they didn’t fit. I had to divide them. Actually Ibrahim Kadriu, journalist, writer, he came and wrote a very nice article, I have it all there. This is how it was.

Sometimes I had problems, there were all kinds of students. There was a student from Gjilan, I forgot his name. I went to, I left my students working, I went in and my wife said she’d make a coffee for me, “I’m working, no coffee.” And then I heard a noise, “Hysni, I’ve never heard such noise,” said my wife. I went there immediately, and I saw a student had put a girl in a headlock like this {puts his arm around his throat}, he wanted to choke her. Fuad, his name was Fuad Islami, I remember now. “Fuad?” He immediately stopped it, the girl’s name was Teuta. I said, “Why are you doing this, Teuta?” She said, “Eh, Professor.” I left it. When we finished, I told Teuta and two other students to stay, “Tell me what happened?” She said, “Well, Professor, I slapped him. “I said, “Why did you…” who knows what happened, “But you shouldn’t have slapped him,” then he had her in a headlock. This was the only problem I had, I never had problems with them again.

Then I said, “Look, I have the right to never let you in my lecture again.” They started crying and said, “Professor, it won’t happen again.” I said, “Be careful how you behave,” I said, “Can you see the issues we have? We are in danger from our enemies, how do I know what your issue is? My family is here.” This is how it was. I worked there for four years. I have all the work, all of them. I will open an exhibition one day and if the Academy of Arts establishes a print studio, I will give them back, if not, I will take them to the museum. I won’t leave those to them, they sell them, give them to people and so on.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Why four years, when the crisis lasted for nine years?

Hysni Krasniqi: Excuse me?

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Why only four years?

Hysni Krasniqi: This is why, you’re right. We went to Pejton, do you know where it is? There was a space for music there, we used it for lectures. We held most of the lectures there, then slowly we came to where the army used to be, UÇK. We worked there for a long time. Then they got us out of there, then we came back to our jobs, because we were liberated.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: How did the war come about? How did your family experience it?

Hysni Krasniqi: Very badly, our family experienced very badly. Why? First, my brother and cousins were executed in the street of Kolovica. There were five people, four of them were executed, one probably was a young man, and he jumped the fence and ran. This is how it was and it was very hard for us.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: You were at home in Pristina or…

Hysni Krasniqi: We were in our apartment. We couldn’t dare to go anywhere. No, not then, because we left Pristina in April, if I’m not mistaken. They beat me and one of my friends on March 16, in front of the District Court, there was a tank there, there were soldiers and undercover cops. There they frisked us to see what we have, “What would I have?” I said. I had around a hundred, 50 dinar, my friend had 120 marka. They took it from him, they said, “You have no right to have marka.” But everyone had marka then.

They took it from him, he said, “Give it back! Why are you taking my money?” He had it in his pocket, he was a great designer, his name is Osman Cakiqi, he also had the KLA emblems in his pocket which he made. He had his own private printing house. Thank God they didn’t search us. He told me, “Take this,” so they saw my university card, that I’m a professor at the Faculty of Arts.. He said “Are you a professor?” I said, “Yes, I am. Why?” I taught in both languages, Albanian and Serbian. “Ah, let’s see. You” he said “You are against the state.” I said, “No, you are wrong.”

They beat him up, broke his teeth and two of his ribs. They beat me up until they got tired. They wanted to break my arm {touches his left arm}, I still have the scars here, you can see in the pictures. They broke it, they wanted to break my leg, I have pictures, I took the pictures after twelve days, because we couldn’t go outside, we were inside. Then I barely got to my apartment. Two of my neighbors saw me at the entrance of the building, I couldn’t walk, they grabbed me by my arm and took me to my apartment.

There I noticed that I was in a bad condition. My whole body was black, blue and red. They took some salt and onions and covered my wounds, I don’t know how long I stayed like that. The ones who took me [to my apartment] were named Mybera and Magribe, Magribe, if I’m not mistaken. Her husband wasn’t there at all, he was in Germany. They took and covered me with onions. I told my wife after a few days, “It smells. I can’t take it anymore.” I removed them and I cleaned up. We stayed for a few days like that. After two, three, or four days some Dragan came, he was head of the police.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: A neighbor or…

Hysni Krasniqi: Excuse me?

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Was he your neighbor?

Hysni Krasniqi: He was my neighbor. He said, “I don’t want to see anyone here after six in the morning.” All the people from the building gathered and we left {coughs}. We went to the train station, you know, the small one in Pristina. We got on the train, my wife held me on one side, my son on the other, only one of my sons was here, two of them were in London. I didn’t see one of them for six years.

Then we went, we got into the train, there were many people with disabilities, on wheelchairs on the train. When we got in the train, they came, the controllers, what do I know, searching the train. “What do you have here?” I said, “What would I have?” They searched me, I had a hundred dinars, they took 50 from me, they left 50, that was it. When we got off the train, there were mines on both sides of the train, so we had to walk on the railroad. When I got out there, we went to Bllace. In Bllace, it was all muddy, raining, and the river flowed there. What could we do? I told my son, “You are in better condition than me, find some long sticks. My brother and I took them and made them into a kennel. We closed it with plastic to protect us from the rain.

We got in there, I saw my [maternal] uncles, they’re from Gllavnik, they were there. “What’s wrong, Hysni?” I told them. They took me to a team of French doctors. They checked me from head to toe and gave me some pills. We stayed there for one day and one night. That day Fatmir Sejdiu came. When he saw me, he said, “You too, Hysni?” I said, “Yes. Along with you.” “Don’t worry,” he said, “It will be okay.”

After a while, a commission from Geneva came, they saw what kind of life we had there. Buses came from Skopje and they got us in there like animals, the windows were closed, the temperature was probably up to 30, 40 degrees. The children used to throw up, so I told the driver, “Open the windows.” He said, “No, no, I can’t open the windows.” They took us to a place called Mojane, it was called Kodrat e Gjarpinjëve [The Snakes’ Hills]. The former English KFOR was there with their tent. We went down there. Some wide but short tents. They gave us chocolates, biscuits and milk and water, nothing else and canned bread. The people started to get constipated.

And they see it, what do I know, the European Union. A team from Turkey came, he was called Demir Eli, the leader of the Turks, Demir Eli, came down to our camp by helicopter. He went down there, he saw what the situation was like. After two days, they made a kitchen. We had breakfast, soup and meat and everything, as well as lunch and dinner. Then, {cough} sorry, then it was done, it was very well done, but we didn’t have a place to shower.

What could I do? I went to the city. My wife told me, “Where are you going? They will imprison you.” “Let them do it.” I got dressed, I shaved, I went to an Albanian neighbor there, “Can I take a shower?” “Yes, of course.” I cleaned up, went to the city, Arbën Xhaferi, we were friends while studying in Belgrade. I went to his residence. When I went there, I went to Skopje there, I went inside. The guard said, “What are you looking for?” I said, “I want to talk to Arbën Xhaferi.” “Look,” he said, “Arbër went somewhere to the Arab States. What do you need him for?” I said, this is what’s happening, “Oh, okay!” He said, “How many people are you?” It was me, my wife and my son, my brother was with his wife and his daughter-in-law, without children, six people. “Hysni,” he said. “I could find you a place in the city, but just you.” I said, “No, no, I’m with my brother. It does not make sense.” “Okay.”

They took us to a village called Sfillare. We stayed there for about a month. The house owner welcomed us, but he was poor. He said, “Look, I have flour.” I said, “Don’t worry. You know what we need? Water and shelter. Nothing else.” He gave us a room, and we all slept there. We stayed there for a month. After a month, we got the papers from London and… I’m a little emotional (cries).

We got the suitcases ready with clothes, we didn’t have much. We had a lot that the Red Cross gave us, but we didn’t take them. We left them to the house owner, we didn’t take anything. We got our suitcases and got on a bus. The bus took us to the airport, and at the airport they asked, “Is someone sick?” My wife told me, “Don’t say you’re sick, they might not let us leave.” I said, “We’re all good.”

We got on the bus and went to Lic. We went to Lic and they welcomed us so well, the only thing missing was a red carpet for us. When we got into a huge hall, elderly women, 70-80 years old were serving us, I felt bad. They brought us soup, bread, cigarettes, stuff, they gave me a pack of cigarettes. I said, “I don’t smoke.” They were surprised. “You don’t?” Everybody smoked. I said, “I never did.” We waited there until they found us rooms to sleep in. The moment we got in, there was a bag with women’s clothes there. She said, “This is your room.” My wife said, “This is occupied.” “No, no,” she said, “It’s not occupied, this bag is for you.” Then we stayed there, and within two days our children came, yes. (cries)

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Your eldest went to Greece.

Hysni Krasniqi: Yes, to Greece.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Did he ever receive a letter to go to the military service, or what?

Hysni Krasniqi: No, there was no letter, he finished it [the military service]. But look, I’ll tell you, he finished the Special Unit against the planes, they asked him to be a soldier, but he did not go. I said, “Son, you can’t go as a soldier.” He finished military service in Ljubljana. My Serbian neighbor said, “How could you send your child to Ljubljana?” I said, “I didn’t send him, the state did.” I found a connection there, Xhelal Qehaja, he was an acquaintance and he [my son] went there and finished it. And I told him, “Son, you have to leave.” He went to Greece, went to Greece, back then it was easy. From Greece he went to France, he stayed with my brother for a long time.

They both spoke English fluently. He stayed there for a few days and he took him to the English Channel. He got in there, he took a bag, he got to the other side. When he came out, he said, “I want political asylum.” He was granted asylum and started his life. He knew English, he didn’t want to take the aid they gave, he said, “I want a job, I speak English.” He found a job as a translator for those who came as refugees, what do I know? He still does that job to this day. Now he works from home, he fosters children. He has four children there. He has a house, he bought a house of his own, he has six rooms, yes. That’s right.

My second son went to Germany, we had a good friend in Germany, a very good friend. He got on the bus here, we found a travel agency that took him to Germany easily. He went there. He was a very close friend of ours, our children always hung out together, he took him to the English Channel from Germany. He knew English really well, he still does. An English newspaper hired him…

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Which year was this?

Hysni Krasniqi: Well, I swear, before…

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Before the war?

Hysni Krasniqi: Before war, way before war.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Not the war of Kosovo, I mean before the war in Croatia or Bosnia…

Hysni Krasniqi: No, Bosnia, before Bosnia, I knew that war would also happen here, he took a small bag, he was very young. You know how old he was? He was 16 years old, not 17 yet. I felt very bad when he had to leave. I took him to the bus station and all his classmates came to tell him goodbye. He got in, then my friend took him on the train to the English Channel. No one asked anything from him, just the ticket because he could speak English. He gave them the ticket but at the border he had to show the passport. They said, “The passport is fake.” “It is true.” “Why?” He said, “I’ve fled from war.”

His brother was there, the older one who went there earlier. He said, “We ask,” actually, he hired a lawyer, a political asylum. And he went to England. He didn’t want aid either, he also started working immediately. He found a job at a cafe. To this day, he still is a manager, manager of a really important cafe. It’s a big cafe, he is responsible for everything, the supply, wages, everything. They work, they’re both good, they’re both married, my three sons are married, they have children. This is how it is, they’re good, they’re very good. They help us a lot.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: So, during the war, you met with your youngest and oldest son.

Hysni Krasniqi: During the war, true. During the war, we met in Lic.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Yes.

Hysni Krasniqi: From Lic, we wanted, they said, “You have to get a house and stay there.” I said, “I want to stay with my children.” The children came to visit us, but it was many kilometers away, they didn’t eat there. They said, “Look, from today, you have one more room, and the children can sleep and eat here. They will stay with their parents.” We didn’t want to be a burden, so I said, “We want to go with our children to London.” We took a bus, and they took us to London to their apartment. We stayed there, I stayed for a month, but I couldn’t stay longer. My wife and son stayed, then it started…

Erëmirë Krasniqi: To normalize…

Hysni Krasniqi: Yes, to normalize. Students asked me to go back, I don’t know how they got the address.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: When did you come back?

Hysni Krasniqi: I came back in ‘99, actually in ‘99, end of September. As soon as I returned, I asked the education community there [in England]. I said that I wanted to go back, they said “Where do you want to go? The war isn’t over yet, you have nowhere to sleep, you have nothing to eat, you have nothing to drink, there are mines.” They said, “We have held you for a year. You can apply for five years and continue to stay here. We will give you a house. I said, “Thank you very much, you have given us enough shelter.” They allowed me. They said, “The first plane that goes to Kosovo, pack your suitcase.” And that’s how it happened.

When I came here, they said, “Your building was demolished.” What do I know?

Erëmirë Krasniqi: In what conditions did you find your house?

Hysni Krasniqi: Excuse me?

Erëmirë Krasniqi: In what conditions did you find your house?

Hysni Krasniqi: The apartment was in perfect condition, meaning it wasn’t destroyed, but when I went inside, you can see it in the pictures. They stole everything: televisions, radios, gramophones, cameras, prints, work tools. I had all my working tools stolen. You can even see the shots in the picture, they stole everything. They took my clothes. But they didn’t steal them bre, the Serbs didn’t steal tea cups, nor did they take the coffee cups. They had broken into the apartment four times. They broke into my apartment four times.

I came back, I went inside, what do I see? Ruined. I was scared to go inside, to be honest. I called KFOR and they checked it, they even went to check in the toilet. “Don’t be afraid, there is nothing here, feel free to work, put things in their places,” but I didn’t know where to start first, clothes, or put the studio in order? Slowly. They [the English] gave me 720 marka.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Pounds…

Hysni Krasniqi: Pounds. No, no, marka, not pounds. They said, “Why pounds? You use marka there.” And a pack of food for the road. When I came here, I started to make a living. First I fixed everything. After a while, a month or so, my wife and son came.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: How did you get the news about your brother?

Hysni Krasniqi: We got the news, my neighbors…

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Yes, while you were here…

Hysni Krasniqi: They were here, but they were originally from Macedonia, they said, “Your brother was killed.” My sister was running away from them at Sharra, do you know where Sharra is? While she was running away, she had a heart attack and they buried her there, there was a pool, you might know. Do you know where the pool used to be? There. When we came back from London, we came and got him out of the grave, two of my sister’s sons and a cousin, it was the four of us, we took and buried him in Mramor, because her sons were in Mramor. This is how it was. They used to call us and say he is in Tetova, we looked on the computer there, the name wasn’t there, it isn’t true then later we found out where he was. It was hard to find him, only his bones, we found them somewhere in Velania…

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Are you talking about finding your brother…

Hysni Krasniqi: Excuse me?

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Who did you find?

Hysni Krasniqi: My brother, we found only his bones, nothing else. A French group then, we weren’t even allowed to open it, it was wrapped in a bag. They said, “How do you know he is your brother?” I said, “I know him even as a corpse.” He said, “How do you know?” “His left leg was broken while skiing and he has a golden tooth.” I said. “Yes,” he said. And they allowed us. This is how it was.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Then your wife and son came back?

Hysni Krasniqi: Then my wife came back, we started life again. My wife started working where she used to, she worked in the Post Office, she started working and I started working in the university, that’s how we started life. Gradually we did everything, we did everything all over again.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: When did you start working again?

Hysni Krasniqi: Working began later, because I still have the trauma, when I get those [flashbacks], I start working on something to forget it. All of these, this is how it was. Look, I hope we never forget it and it never gets repeated. I swear! Do you see what kind of a government we have? You see. I hope he can do something.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Do you remember Independence Day?

Hysni Krasniqi: Excuse me?

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Independence day…

Hysni Krasniqi: I remember, it was very, it was…

Erëmirë Krasniqi: How did you start that day?

Hysni Krasniqi: Excuse me?

Erëmirë Krasniqi: How did you start that day?

Hysni Krasniqi: For me, it was a great burden being lifted, a great joy, it seemed that we were flourishing, we were renewing, a new life was coming for us. This is how I felt, to tell you the truth, but you can see that we didn’t go the right path, one here, one there…

Erëmirë Krasniqi: What did you do that day?

Hysni Krasniqi: Excuse me?

Erëmirë Krasniqi: What did you do that day, did you go out or…

Hysni Krasniqi: Yes, we did, we celebrated like everyone else. But look, I’m not a person who loves celebrating, I’m distant in every occasion, the good and the bad, I handle them the same. I’m distant with everything. I know what joy is, what misery is, but I stay cool, it’s better. For example, I don’t go mad, and lose myself. One should always be aware of what one does, both in the street and at home, as one should be aware everywhere.

To some, why are you firing guns? Why are you firing guns? You had a time when you had to use guns, but not in freedom, not in weddings. Celebrate with your voice, not guns. What primitivism is it to shoot with a gun, bim bim bim {onomatopoeia}. What is it, tell me? It is, to tell you the truth, somehow it goes out of the human psyche, it goes out completely.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: I don’t have any other questions, but…

Hysni Krasniqi: Excuse me?

Erëmirë Krasniqi: I don’t have any other questions, but if you have any questions, not questions, but anything to add about your work. Something I haven’t asked you, a moment you could speak in more detail about.

Hysni Krasniqi: I have the pictures.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: We will look at them after the interview, it’s something we can see…

Hysni Krasniqi: Look, to tell you the truth I could have worked much more, but I was part of a society that didn’t understand me. I had so much energy and I had positive energy, not negative, but people created obstacles. Back then, the number-one athletes were never allowed to progress, they stopped them. First of all, they gave my student a studio, but they didn’t give me a studio. Why didn’t they give me the studio? Because I wasn’t in their hands. I’m not in anyone’s hands, I’m in the hand of myself and my people, not in the hands of any bad dogma that works against society, against the people. I never got into the dogma of anyone seeking anything, because I saw that this is not okay, this is not okay.

I hate selfishness. In life, I hate three traits: lies, theft, and betrayal. For me, these are the worst things that exist, yes. Lies should be told, we know when they should be told, for the country, for the country, but not for just about anything, like for riches, to become rich for yourself, by lying.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Something about you, something about your work I didn’t ask?

Hysni Krasniqi: Excuse me?

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Something about your work that I didn’t ask about.

Hysni Krasniqi: My work, look, to tell you the truth I connect to nature, I love nature, I love ecologic nature, not with waste. When I see, when I see on the television, when they show that waste, look, that is the greatest catastrophe of our people.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Where did you find your inspiration?

Hysni Krasniqi: Excuse me?

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Inspiration…

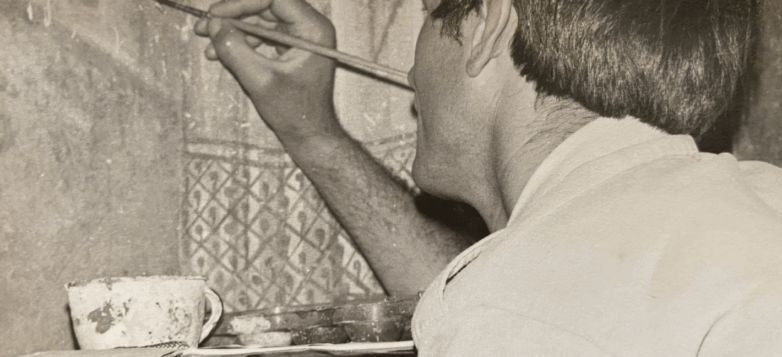

Hysni Krasniqi: I mostly find inspiration in nature. I take fragments from nature and try to live through them, live it with my heart and soul, and draw it on paper or paint it on canvas. For me, that’s what’s important. I’m not the kind of person who makes many images, I make portraits of sufferings, I have some portraits during the war with injured heads. I could’ve done a lot, but they stopped me at my peak. That’s what matters.

For example, I have the Crops Cycle. Why crops? Crops because our people suffered from starvation, suffered from starvation. Then I have the Twig Bundles. What are the twig bundles? It’s a tool which our farmers always used, they used it to level the land, to dry trees, that’s what bundles are, like protecting the country, the yard, that’s what they are. I had those.

Then I have The Fireflies. What are the fireflies? The fireflies are the messengers of spring, the first sign that the crops are ready to harvest. Then this is how we knew that it’s the time of the harvest, and that’s what fireflies are to us. Like a phoenix cik cik {onomatopoeia} sending out the message that somewhere the time has come to harvest. Like that. Then I have The Memory Flowers, the place I was born in, Llukar, though I spent more time in Pristina. The place I was born in is covered in flowers, snowdrops, violets. What a wonderful scent violets have, it’s incredible, as if it were a perfume, I don’t use them ever, only when I shave. Then there is some weed called Elmetum, maybe you’ve heard of it? If you put two leaves under a child’s head, they sleep immediately, they rest. It has a nice scent. These things inspire me, ground, greenery, leaves, these are my inspiration, yes…

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Thank you very much.

Hysni Krasniqi: You’re welcome.

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Let’s end the interview here.

Hysni Krasniqi: Excuse me?

Erëmirë Krasniqi: Let’s end the interview here.

Hysni Krasniqi: However you want, I can tell you whatever I know…