I felt very secure, the conditions were very good, the hygiene was good, I had no obstacles with my friends, there were various communities: Bosnians, Serbs, Albanians, Turks, but we got along very well, we lived all together. But I was the only Roma working in my department, but there is a saying, ‘One finds themselves in the setting where they live the way they reflect.’ But I never felt bad there, I didn’t feel bad in the elementary school nor in the high school or in the high pedagogical school, I was the only person from the Roma community in my classroom but I never felt bad, my friends didn’t feel bad either for having a person from the Roma community among them. We got along very well at that time…before the war exploded, then there were some agreements which had to be signed. I don’t know! Most of Albanians quit their jobs not only in the factories, but in schools and everywhere else…

Urban Memoryscapes is an interdisciplinary project done through the collaboration between Lumbardhi Foundation and Kosovo Oral History Initiative. The project consists of research, archiving and exhibition-making with a focus on the the social, cultural and economic history of Prizren in the second half of the 20th century. Through this project ten participants will be equipped with tools to document the past and interactively work with the collected data to build a digital archive, online and offline exhibition, a publication, and most importantly producing knowledge about their communities and engaging in a learning process about a critical period that has been formative for the cultural and urban identity of Prizren and its inhabitants.

This project is made possible with the support of the Franco-German Cultural Fund and the French and German Embassy.

Mehmet Galushi

EducatorFetije Kasemi

EducatorEvery year, we went to Macedonia, Ohrid, Dibra or any other place in order to see the language differences, because we speak differently from them, we spoke gegë there. In ‘72, çak [colloquial], it happened that we started to speak the standard language. It was difficult for us, more difficult for the students and even more difficult for the parents because of additions and suffixes…but they reacted to it, ‘Tell us, tell us how it should be.’ We had a hard time getting used to it, then it seemed all normal to us after a few years. Wherever I go for official visits, I still speak the standard language, I can’t speak the gegë.

Fikret Menekshe

ShoeshinerBecause, we, our Romani have a lot of knowledge. A Turk or a Serb or an Albanian cannot play the same music. That means, we have a lot of knowledge, we, the Romani, that is why they always invite us, for example, you can take a Turk, people can take a Turk but he cannot play the music the way I do, or the clarinet for example, a Turk cannot play it the same way as I do. They can play a little, but that is not enough. This is it…

Myzejen Hoxha

LibrarianI didn’t have children. My husband also died in ‘82, in the late December, his name was Reshat Isa. And since then, I only read, sometimes I do handmade stuff, I used to work gobelin tapestries and I still do sometimes. […] I really really miss that time. Even though I am old now, I really miss the staff of that time, we were a great staff. I still miss them, I come here to take books, sometimes I come to visit them, ‘How are you, what’s up?’ and they also invite me, the director, whenever there are library holidays.

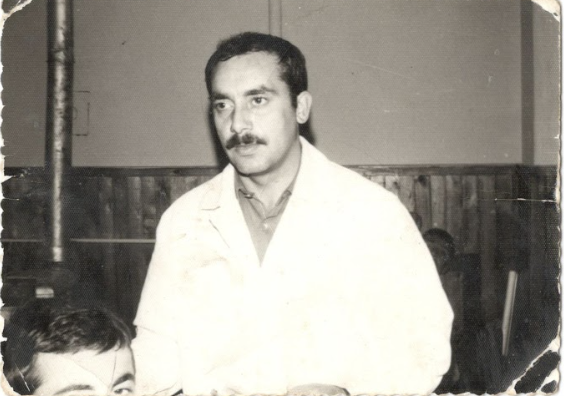

Fadil Softa

Chemist/PharmacistRadmilla Rexhepagiqi was [my teacher] she was Muslim, chemist…When she explained the compounds, structural molecules, somehow I didn’t need to study at home…But I got everything directly in class, I listened to the lectures so carefully that I never had to read at home and I always got fives.

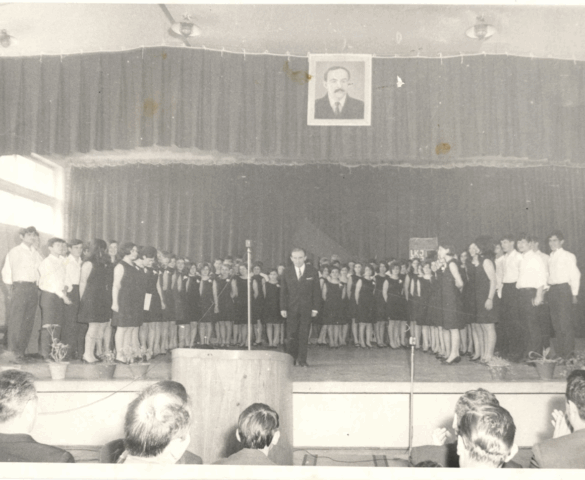

Besa Krajku

LawyerI have one remaining memory from the time I was part of the assembly, it is the celebration of the hundredth anniversary of the Prizren League on June 10, 1978. It was an amazingly organized event, it was great, I believe Prof. Dr. Pajazit Nushi who was also the minister of culture and education was in charge for the event. We collaborated a lot at that time because we needed to collaborate, because renovations were taking place in the League’s building. I remember there were some poor people living in that building, then apartments were given to them, the building near the League was renovated [the current museum]. All that took place for the hundredth anniversary, Agim Çavdarbasha sculpted the statue of Ymer Prizreni [and Abdyl Frasheri]. I remember that Albanian opera was Goca e Kaçanikut [Girl from Kaçanik] of composer and professor Rauf Dhomi was first performed in Kosovo on that occasion. The ceremony took place at 8 PM in the evening in the sports center, there was direct broadcasting of it all around Yugoslavia, from Slovenia to Pristina, it was a very well-organized event, but then after ‘81, they started to fade away…

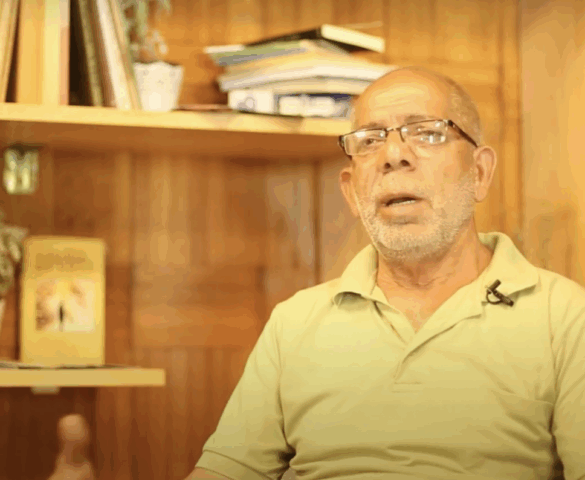

Osman Osmani

Textile engineerWe often use this word, that when a Roma child is born, they immediately know four languages, because the social circle here requires it and we have no problem with that. […] What will always remain registered in my head is an image which was also a motivation for me to continue motivating my children, I am talking about one moment when, my mother who always walked me to school and back, and what was interesting, she knew the rule that parents needed to follow their children, to help them with the homework and she asked me, I mean, when I returned from school, to do my homework, to write, to do my mathematics homework, or writing-reading sessions. And, until the second or third grade, I really didn’t know my mother was illiterate, because she always hovered over my head, I thought that she knew what I was doing, what I was writing and reading. I thought that she understood.

Hadije Gështenja

TranslatorHe started to screen films in Kosovo, then after a while he went also to Albania as Italians were there, they had cinemas in Tirana. […] The youth watched films so much, so much. Not only the youth, but also the elderly. My father would tell me about a friend of his, he’d go into the cinema at 4, he’d get out, he’d enter again at 6, he’d get out and enter again at 8. He’d watch three films a day. […] Then when I grew up, there were those leaflets, with the content of the films, my father would give me, I’d look at them, read them and propose the ones he should pick. I knew so much for films, also for artists, directors, and subjects.

Rexhep Hasani

LawyerI decided to stay in Prizren because I liked it the most, my children liked it better here. Because I came here from ‘66, they all made friends here, they got adapted. But I got adapted too. […] In Gjilan, I told you, I had a very good time in Gjilan but here I had my friends. I could go to Pristina, because the whole Kosovo is there, Podujevo is there as well as Drenas, Peja and Gjakova, everyone is there, the whole Kosovo is there in Pristina, but I liked it here better, I got closer friends with whom I still hang out […]

To be honest, life in Prizren hasn’t changed much, it has just gotten more dynamic, and here I am talking about the nightlife, because there are no big changes. […] We had, Prizren had only one korso, there were no coffee shops like nowadays, there was the korso in shadërvan., then they moved it to Marash […] from the rock bridge, the iron bridge […] that is where the korso was, from the rock bridge to there. Before that it was in shadërvan. But it was very good, life was dynamic […] There was not a single night when we wouldn’t go out, only if we were on duty or something […] not much in coffee shops, but on korso, we would go for walks.

Xheladin Kastrati

ViolinistI didn’t know that the national anthem of Croatia is in Albanian. This book {points towards the book}…this song was made by Kol Pjetër Shiroka, he translated it into Albanian from Croatian, that book still exists. I took that song because it is a four-vocal song. I performed it and I didn’t know, when I saw people stand, I didn’t understand why they were standing and somebody came to me and said, ‘Once again, please.’ Crying, the audience was crying, ‘Once again, please, once again!’ I realized that it is the national anthem of Croatia, ‘Oh my beloved fatherland’ is the title of the song.