Part Two

Aurela Kadriu: Was there a Jewish community at that time?

Mihane Salihu-Bala: There were very few Jews at that time so the consoled community as such… but we weren’t part of it at any time. It was followed more through the tradition and through other things, but not in an organized way. Because there was no synagogue. There wasn’t a big family connection, I mean, there wasn’t, they didn’t have…Later when I started researching due to curiosity, I found out that there was one, but they left in the ‘70s.

I mean, they weren’t organized. I mean, there were individuals who were part of different families be it through marriages, inheritance or through other ways. But those who spoke Albanian were very few.

Aurela Kadriu: Can you tell us about the holidays atmosphere, the so many holidays that you had in your family? Your memories…

Mihane Salihu-Bala: I told you, it was interesting. When Eid came, everybody baked baklava, so did my mother. There was the other holiday and we had a different cake…or the new bread holiday, we had boiled wheat, we had grape. It was interesting because we gathered and not because of a certain holiday. I remember two other moments in the family, the circumcision ceremony for my brothers, and the moment of becoming a woman (smiles). The moment when the menstrual cycle begins for the girl, we had a special dinner, a special dinner. I remember this. All my sisters and I had a special dinner. My brothers had a dinner, but not a religious ceremony. This was something to mark ourselves within the family. I mean, it was something special.

And the nuts cakes. They were…but they weren’t baklavas. Then the apples with honey, they were another moment which we didn’t… “Today we have apple with honey…” But for example, we didn’t drink wine in my family, we didn’t use wine. So, it was an interesting mixture.

Aurela Kadriu: Can you tell us about the time you started school, this is another stage of socialization?

Mihane Salihu-Bala: The socialization was difficult in that circle, because we lived at my mother’s house. The circle didn’t accept us well. I had to fight for survival at school. I had to study a lot and become better, there was not big pressure until the fourth-five grade maybe, except about the way I dressed. I mean, we were all children of working class or the unemployed of the time. I am always speaking about those who grew up at Kodra e Trimave, I am not speaking about those who grew up in the city center, which even though not so far, was a very different lifestyle because of the economical conditions, because of family adjustments, the relations within the family…I mean, for me, the first year of high school is the one where social changes started for me.

I went to the Ivo Lola Ribar gymnasium,[1] which is now called the Sami Frashëri gymnasium and it was considered an elite school, for those who were talented and were connected to the leading structures. There was no admission exam but the listing was done according to the points and the success, so I had the luck to be accepted. I was studying at the programmers’ department at that time, we were the first generation of the fourth-year system in gymnasium. And I was part of a very good class, where the students were very diverse, I mean, there weren’t only the children of the elite, but there were also children of simple workers, various professionals.

And I remember that since it had a great name as a gymnasium, we had to work a lot. It wasn’t possible to get a two or three because you lost…the goal was to always be better. And I had the fortune to be part of a very good class where there were students from diverse families and circles. In my class, there were students who weren’t only from Pristina but also from the surroundings, so this created a kind of balance between the rich and the poor.

I laugh a lot when I think about it now that Victor Hugo was the promoter for me, with his book Les Misérables. We struggled a lot, unfortunately I became part of the generation that experienced ethnic segregation at schools,[2] I mean, when the school is divided, when the first shift belongs to…

Aurela Kadriu: Excuse me, in which year did you go to high school?

Mihane Salihu-Bala: ‘86 – ‘87.

Aurela Kadriu: Okay.

Mihane Salihu-Bala: ’86, ’87, yes, because I finished in ’90, ’91, I finished high school in the school year ’90, ’91 and then the ethnically based segregations began. I was part of the time when the poisonings[3] of elementary and high school students took place. I mean, I was in high school at that time. And the torments of ’86, ’87, ’88, miners’ strike, various protests. I was part of their growth and I remember the protests and demonstrations of ’81 because they didn’t allow us to go to school and there was noise, there was the constant alarm and the helicopters flying very close to the ground, the small airplanes or what were they…the gas, the poison that was thrown, the teargas that was thrown from the helicopters and from various forces.

Since the protest was taking place in the city center, people escaped through Vranjevc, through Kodra e Trimave and the police came after them throwing teargas. We were very, I was very little, I was eight, seven-eight years old but I remember it because we were bombarded with various information from the people at that time. I remember the students escaping and various students lived at our place at that time, relatives from various surroundings came to live at our place.

And I remember the students’ conversations, “This is bad, this will become even worse. We have to have a republic, no it won’t become a republic, no it has to be another shape…” So, I was told the story of resistance very early in my childhood. But, I started my continuous activism only later in ’88, ’89.

I wanted to talk about the Blood Feuds Reconciliations movement, but first there were the protests of ’86, ’87, the miners’ strike when I was in high school. We attempted to skip classes in order to join the protests, but due to very strict rules and security, we only joined the protests after the classes. We were told to not remove our uniforms so that they would know who is a student and who isn’t, but with or without the uniform, we joined the crowd.

I remember the protest when we were in the city center and the whole crowd was shouting, “Kaqusha, Azem,” that was an interesting slogan. These are the very beginnings of my engagement…

Aurela Kadriu: Did you have, excuse me, before talking about your engagement in the Blood Feuds Reconciliations movement, I would like to know, as young students, were you aware of why you were protesting? Or did you join the protests because of…

Mihane Salihu-Bala: No, no, no. The information was very good. The awareness of why it was happening was high, exactly because of the changes that took place, that started taking place in the former Yugoslavia system, which means…we were informed, I mean, we weren’t…Even though the communication channels were more limited, much more limited than today, we knew why it was happening. Because however, the conversations, movements were very active at that time and the daily politics became part of our lives. I mean, we, the children, weren’t excluded from the effect of the daily politics.

So we were in the streets, some of us with passion, some of us because we wanted to and some of us because we just happened to be there. Somehow, we became part of the protests. And our growth in the Pristina streets didn’t happen gradually, but very quickly. Because from being very innocent, to say conditionally, we became part of the movements, of changes, even though I cannot say that we were innocent. I am speaking about my generation, starting from ’81, we grew up with the fear that there would be war, there would be changes. It was a systematic way of state pressure.

And somehow this makes you have a different approach. Because, personally, starting from ’81, I grew up with the fear that there would be war. And this war will explode today or tomorrow or this or that, being haunted by this idea for twenty years is not something small. I mean, as a child you grow up with the idea of the fear that there will be war. We didn’t think that the war would be like the one that happened, but we always had the image of the Second World War, which followed us, be it in literature, be it at school, be it in the collective memory of the people. The continuous fear makes you grow up under its pressure.

This was also part of the protests and demonstrations of ’86, ’87, ’88. Because when the miners’ strike started, we were all 15-16 years old and we constantly were afraid of what would happen the next day. Add to that the fact that I had the luck to be in a circle of people who were students at that time, and the students thought differently. We had a lot of information, maybe not the right information, but we had a totality of information about what was happening, what was about to happen. And the Albanians were hesitant to be part of the whole system and that made us think differently, because we were excluded, we were different, we weren’t part of the totality of the system.

Add to this the fact that we had very big lingual and cultural differences, maybe cultural ones were bigger. Add to this the fact of religious differences, even though they weren’t emphasized, as an Albanian, you were treated as a Muslim, even though there were other religious group among Albanians, but they were very small. We were treated differently.

I remember for example, what I remember maybe is different from the perception of the time in Kosovo, is travelling to other places without borders, without passports. However, Yugoslavia was a big place, and we could take the train from Fushë Kosovë to Krajina. It was a totality, it was a change. But the moment you passed Kosovo, there was a completely different world. Even though we travelled by train or by bus, it was a completely different world. Or maybe I can make another description.

You would return from various countries in Yugoslavia, the closest big city from Pristina was Nis or Belgrade. And the first encounter in Kosovo was Merdare or Vranjevc, I mean, you come from a place with wider streets…speaking about Belgrade, it was a bigger and more developed city, and the first view of Pristina is Vranjevc. The clay houses surrounded with tin fences. Extreme poverty which was one hour or two hours from another city.

I mean, the difference was very big. Even though the city center is twenty minutes on foot from Vranjevc, but the difference was very big nevertheless. In the city center there were high buildings, which we called palaces, that’s how we called the skyscrapers and only twenty minutes from that, there was extreme poverty. So, these differences were a collective and individual pressure and these differences made me a different person, I aimed, I had other goals, but I lived where I lived and…

About the question about the information, there was a lot of information. How it was transmitted and how it was perceived, accepted or used, that is another discussion. On the other hand, we have to mention the fact that at that time, we received the information through written media. Newspapers and televisions were however, controlled. But other information was verified. There wasn’t fake information like nowadays because there was a filter, there was a structure and system that released the last information. But on the other hand, there was the information followed from one person to another, they were life experiences, opinions, various viewpoints…and this mixture of information was enough for us to have enough information, but not always the correct one.

And this is when the Blood Feuds Reconciliation movement begins, I was in high school. I wanted to join them and I joined them first in the neighborhood, I joined the activists in my neighborhood. For me it was interesting to be part of it as a high school student, to go to a family, or back then there were the big rooms, the oda,[4] because in Pristina we didn’t have the typical oda, but we had a bigger room for the guests, and listening to people trying to reconcile two families. Their reactions, acceptance or non-acceptance of such a moment of mediation, everything was so interesting for me because I heard various stories. I heard two different versions of the same event, two different perceptions, two different viewpoints of the same situation.

And what impressed me mostly at that time was the way that families that were in enmity {makes quotation marks with her fingers} lived their lives. The way the family of the victim was treated and perceived by the people, how they were pushed to avenge the blood, or the family of the perpetrator on the other hand, they often lived with the feeling of guilt, shame, isolation, mock, being pushed to continue the crime. It is interesting how little these things were talked about. But there was the pride of avenging the blood, or putting the other person in conditions of social, spiritual and physical isolation. And when the institution of besa[5] was explained, for example, that was for me…I read, I heard about it, but that was the first time I saw how it really works, and it was very interesting for me.

And the attempt of so many people to do something for themselves was maybe the great bend, even though I don’t remember many meetings. Not many, but several meetings took place in my neighborhood, I mean, at people whom I knew, who were part of my everyday life, and I know how difficult the process was. I mean, it couldn’t finished at the first time, it took two, three times, sometimes even ten times, maybe a whole night, a whole day, and those people who were part of that process were patient, courageous. This was something that I will never forget, on one hand the insistence of people on reconciling the families and on the other hand, the resistance of the families to reconciliation.

Looking at it from the perspective of today, I would explain it differently, back then we leaned on nationalism, on the greater good, on the idea that people needed to forgive because we shouldn’t have such…We tried to work in the social sense within the family, but when it failed, they leaned on the national cause, on the greater good. This made the formation of…even though I might not be the best mediator, but this is an approach that marked my life. Maybe it motivated me to continue with my engagement within my neighborhood, with simple things like cleaning my street, removing the garbage that was collected in my neighborhood because of the life parallel system. The life parallel system took place in many fields.

The company for garbage collecting was working in the city, but it wasn’t working in Vranjevc. And people, since they weren’t aware and sometimes they were in a rush or so tired, so they started depositing their garbage in a certain part of the neighborhood. That was near the electric substation in Vranjevc, in the middle of Zenel Hajdini and Asim Vokshi elementary schools, exactly where several streets meet, people threw their garbage there. And I remember that there was a lot of garbage there and we couldn’t pass through that street. When it rained, the garbage was flowing all over like canalization, when it was warm, it stank. I remember that the first gatherings of the Lidhja Demokratike[6] [Kosovo Democratic League] at that time, the Lidhja e Shkrimtarëve [Writers’ League], the forums, the social organization of the neighborhood safety, to save the neighborhood from various police attacks, various police interventions. And I remember that the first activity where I was physically, spiritually and mentally engaged is the one for the garbage removal.

What I was impressed mostly by that day, I don’t remember the date, it is so bad, is that elders, youngsters, children, women. People voluntarily brought their tractors, their carts, their shovels, brooms and everything else in order to remove the garbage from the neighborhood. I remember so many police patrols came to check what was happening, because however, we had to get special permission because we were more than five people, a group of people, we had to let the police know. I don’t know how the technical part with the state was done, but I know that there were a lot of police patrols coming to see what was happening. And it was something to remember that they took a lot of photographs of us removing the garbage. This is my first engagement, and then when it started, when we remained outside the school, in ’91-’92…

Aurela Kadriu: Can I interrupt you a little more? What were the main slogans of ’88, ’86, ’87, ’88?

Mihane Salihu-Bala: No, no, I don’t remember them. I remember, “Kaqusha, Azem, jemi gati përherë.” [Kaqusha, Azem, we are always prepared], it was an imitation of the socialism slogan beyond the border [in Albania]. They had something to do with…I don’t remember Democracy being mentioned. I don’t remember, maybe there was another slogan, “Minatorë jemi me ju, Trepça është e jona.” [Miners we are with you, Trepça is ours], the mother of all slogans was, “Kosova Republikë” [Kosovo Republic]. There were other slogans, “Të drejta, më shumë të drejta.” [Rights, more rights]. I remember in ’86 – ’87. While in ’81, there was, “Duam bukë” [We want food], this I remember, except, “Kosova Republikë,” another slogan that I remember is, “Duam bukë.” Was it right or not, I won’t talk about that right now because it is in the past. But those of ’87 – ’88 have more to do with saving the sovereignty, autonomy of Kosovo at that time, and they were connected to the political leaders of that time, saving the values, but I really don’t remember all of them except the dominating one which was, “Kemi të drejtë.” [We are right] “I duam të drejtat tona.” [We want our rights]. And Kosovo Republic. I don’t remember any slogan using the word democracy, maybe there were, but I don’t remember them.

Aurela Kadriu: In the Blood Feuds Reconciliations movement, maybe we could stop and talk about it in a more detailed way, when did you join it, the way you joined it and if you remember any specific occasion of reconciliation which you were part of?

Mihane Salihu-Bala: I joined them through a maternal cousin who was a former policeman, since the new policemen were expelled from the Kosovo Police. He was an activist, in fact why the policemen who had been fired from the Kosovo Police were engaged is because they knew the people and the field, they were professionally, physically prepared in case protection was needed. And I went to the first meeting through him. I don’t remember specific occasions, families, because there were a lot of families. I remember that I was a passive observer in the beginning, we weren’t there to speak because there was no space, we were there just to support.

I remember a family, I don’t remember the name right now, that forgave the blood of their son, but why I remember that occasion is because two-three murders had happened one after another for a very long time. It was a thirty-year-old conflict, it wasn’t recent, that the one who forgave the blood had to forgive it for someone e had never met, this is a moment that I remember and that I was very impressed seeing people trying to go beyond themselves for someone they didn’t even know. I mean, whether it was the grandfather, or their father’s paternal uncle, or their father’s brother, I don’t remember, but it was someone they had never met before. The hardest moments were when after the refusals and everything, mothers took over to forgive the blood of their children.

That is a moment which at that time I didn’t think about as going beyond yourself, but I told you that it was the idea that they were forgiving for something greater, so that there wouldn’t be brother-killing among Albanians. But later when I started analyzing it, I have come to a situation where I am a mother too, that is something irreplaceable. It was a moment through which maybe without being aware of it, we skipped whole stages of social development. With all the goodwill, with all the desire for them not to live under the pressure of fear, asking a mother or a father to forgive the blood of their child, was a very courageous thing to do. I don’t believe I would do something like that now, I don’t think I would insist as much as they did at that time, but maybe people found the strength to do something like that.

Aurela Kadriu: Can you tell us about what you were telling us before I interrupted you, about the ‘90s, about the parallel life?

Mihane Salihu-Bala: Eh, the parallel life is, as I told you, the school year ’91-’92 didn’t begin for us. The whole society was lost. We heard everyday how my classmates, my friends left Kosovo because of the massive military mobilization, and in order to survive the forced military mobilization, people started escaping, especially boys, massively. A kind of a double social death, physical and spiritual, because people started leaving, the city, respectively my neighborhood was empty, from the people that I knew, from my friends. The school year ’91 didn’t begin and we didn’t know what was about to happen…

Aurela Kadriu: You still hadn’t finished high school then?

Mihane Salihu-Bala: No, I had finished high school, I was registered as a student of the University of Pristina at that time.

Aurela Kadriu: At which faculty?

Mihane Salihu-Bala: At that time, I enrolled at the Faculty of Technics, the department of Energetic, Electro-Energetics. And I remember the preparations that were done in order to start that school year in the schools, in the parallel system, in private houses, I remember that we started the academic year in February-March, ’92. And since high schools and the university were denied their buildings, the parallel system took place, elementary schools were still working. We organized that way, that elementary school students went to school in the first shift, while students of various faculties went in the second shift in some of the elementary schools of Pristina, of Vranjevc.

But this wasn’t enough, the space wasn’t enough and in a very short time, the house-schools were opened. A very special moment is when the professors of the University of Pristina opened the doors to their houses to give lectures to their students. This is something we don’t talk much about, we don’t mention much, but professors of the University of Pristina opened their doors first. People of goodwill opened their houses, no matter the difficulties they had, some of the houses were constructed, some weren’t renovated, we started sitting in bricks upon which we put boards, I mean, boards and bricks were our seats.

I remember that lectures were held in various parts of the city, depending on where there was the opportunity for them to be held, and within one day we walked from Dragodan to Bregu i Diellit and to Xhemajl Ibishi Street, I mean, in three different locations within the city, going from a lecture to another was a kind of marathon. Then the police pressure, because there were more police forces in the streets, the police were very active and wherever they saw two-three people, they stopped them, especially if they were young. I joke about my time now, I say that it is that time when I learned all the narrow streets of Pristina, because taking the main streets wasn’t a very smart thing to do, and so we learned all the narrow streets of Pristina, not only us who were from Pristina but also those who were coming from other cities of Kosovo got to learn the streets of Pristina at that time. I mean we, the students of that time knew all the streets of Pristina, it was an interesting situation because we wouldn’t learn them in a normal situation. And then they moved the students to periphery parts of the city, the dormitories weren’t working for Albanian students. The university buildings were not open for Albanian students so the life of the Albanian student was taking place in the periphery.

They applied strict safety measures at that time, strict police repression measures. Add to this the extreme poverty that started growing, most of them had to quit their studies, I mean, they had to leave, to survive. And this is how the second generation of migrants from Kosovo starts. This is the greatest bend that ever happened and they had economic opportunities or other ways to go abroad.

Many friends of mine from high school who were very good students and became educated and successful people even in the places where they went, they had to quit their studies in order to save their heads. Those of us who remained, not all of us remained because of idealism, but because of the circumstances and conditions in which we lived. Best part of this is that we survived and continued our education even under those conditions. Even though today it might seem that…Considering that from a University you return to a faculty, to a room with boards where there are not even fundamental conditions to study, however, we have to be thankful for the effort of our teachers first.

In the social sense it cost us a lot, as a cultural totality, but thanks to the continuity of education even with the very difficult conditions, we are here today, because education was cut and we waited for a economic or political solution at that time, we would have many illiterate generations and the consequences would be much more harmful. But, no matter the difficult conditions, we wanted to prove that we can make it. Even though there is a lot of skepticism about it, looked at from this perspective, I think that the parallel education system created a continuity of survival. And no matter the harm we were done as a society, because all the enthusiasm of the young people to get educated, to become professionals was stuck in the lack of education opportunities. But now I think that it was the only smart solution of that time.

Aurela Kadriu: Can you tell us a little about students’, I know that you were part of…

Mihane Salihu-Bala: Students’ protests…Students’ protests, seems like my whole life loops around students and students’ protests. Those protests didn’t begin in ’97, they began in ’92-’93. I remember that I was also active in organizing them in ’92-’93. There were just a few protests at that time, two or three of them where we demanded our return to school facilities, the right to the sovereignty of the university, the fundamental human right for education and so on, but I remember the police repression as well as the tortures we had from the police during those protests. And I remember there was not a social consensus, but a sudden silence of the protests in ’93, I mean there was no attempt to organize any protest from ’93 to ’97 because the police repression was so heavy and on the other hand there were wars in the region and on the other hand there was the military, physical inequality of the Albanian nation compared to the others.

And at some point we had enough of waiting for it to become better, because no matter the current opinions, we survived thanks to the courage to initiate the peaceful movement in Kosovo. Maybe people’s desire was to start the war earlier, but we weren’t ready for war or for resistance, armed resistance, not of that kind of resistance, that kind of format in which the countries around us were, or former Yugoslavia. The peaceful resistance had two good things, people’s patience was tested, and we were taught how to survive in abnormal conditions.

And maybe seen from this perspective, maybe it was better if it happened earlier, I don’t think that it would be better if it happened earlier or that it could happen earlier, if the war that happened in Kosovo in ’98-’99, exploded in the same manner but in ’93-’94, I think the consequences would be even worse, there would be a lot of damage, and I am sure one million people would no longer live. They wouldn’t only go missing or migrate, but they wouldn’t exist at all because the military capacities of former Yugoslavia were very big at that time for a country with a territory like Kosovo. Add to this the fact that they would be against a small unit, as Kosovo was at that time and the consequences would be very big. It is not that there weren’t consequences from the last war in Kosovo, but I think that the mindset of the peaceful resistance helped, it had a positive effect and a positive effect on saving human lives in the first place.

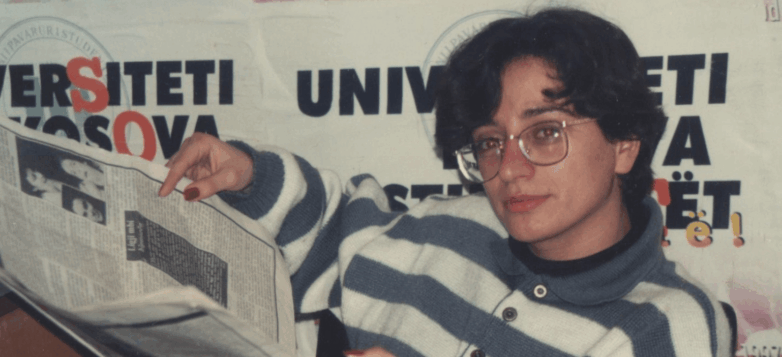

Other things could pass with various calvary and sacrifice. In a way, the postpone of the agreement that was introduced from Sant’egidio for education, it’s infinite prolonging, the lack of opportunity to reach an agreement for it to happen, that proposal pushed me to join the students’ movement and the Unioni i Pavarur i Studentëve [Students’ Independent Union], not the students’ movement, but the Unioni i Pavarur i Studentëve in ’96, now I was a student of the Faculty of Philosophy, because in the meantime I stopped the Faculty of Electronics with the goal to go to Zagreb, but then the war exploded there and I chose to return to Kosovo.

Aurela Kadriu: Can you tell us a little about this period, how did you interpret it when you went there as…

Mihane Salihu-Bala: It is interesting, I applied in Zagreb in the academic year ’90-’91, Department of Criminalistics. But since my diploma was issued by the Republic of Kosovo, my documents were not treated there but they were sent to Belgrade and I wasn’t accepted, and only later I found out that my documents, my application, my request were in Belgrade, because they were transferred in an arbitrary way to Belgrade because they were documents from Kosovo.

My family was in very bad material, economic conditions at that time so through some friends, I was offered the opportunity to be a student with connections in Zagreb. And I accepted to go and see for one semester, and I remained there from September-October ’93 to March ’94. It was the peak of the war, everything started getting worse and since I had no chance to stay in Zagreb, returned to my family, and I was in a very bad mood because I really wanted to study and do good things, and in the end I remained home. I had no material conditions to return to the Faculty of Electronics, because it required books, exercises and everything, at my home there were already two students, because my brother was a student now and my sister finished high school and was waiting to enroll at the faculty, so we had to set our priorities.

The economic situation of my family got worse and one day my mother put me in front of an ultimatum, because getting married was trendy at that time, “You will either go to university, or make a choice.” And that is how I decided, I took my documents and went out. I saw some students going towards the Dubrovniku street and I went after them so I went to the Faculty of Philosophy, not because of a special choice, but I just wanted to see the opportunities. I went to the secretary of the faculty and asked them, “I am interested to enroll in your faculty, is there a chance?” We are talking about April ’94.

I remember a person who was working there, his last name was Kastrati, a very good old man, he said, “Where were you earlier?” And I said smiling, “On the streets!” Without any complex. He said, “How can we accept you now?” I said, “But I have an index of the Faculty of Electronics,” “Alright, you can come, but why don’t you finish that one?” There were no more words, they made it possible for me to transfer from one faculty to the other, I mean, not from Zagreb, but from here. I went home and told my mother, “They accepted me in the faculty.” And poor her, she didn’t even believe that it would happen, but that was her ultimatum, either that or this, there is no grey. And my first time at the Faculty of Philosophy was…

Aurela Kadriu: In what department?

Mihane Salihu-Bala: In the Department of Pedagogy. My first lecture, I mean, the April term was about to begin in a few days and I went at the first lecture in Ethics class. And the professor, I don’t remember his name right now…Mavriqi, professor Mavriqi, he was the first professor that I met and the classroom was a room at a shop in a dead end street. There were 150-200 students of the first and second year preparing for the April term of exams. I entered, I remember I had very short hair, not all shaved, but very short hair, I was dressed in black, I wasn’t as fat as I am now, I was much thinner. Professor Ramush Mavriqi started speaking about Immanuel Kant and this was the first lecture that I went to, nobody was speaking or making any question.

In the meantime, I raised my hand and asked a question and he said, “Who are you?” I told him who I was and he said, “Why are you here?” I said, “I am here to get to know who you are, to get to know about the book and get the exam in the April term.” He said, “There is no way you will take it in the April term.” And this is how it started, I really passed the exam in Ethics in the April term because I went home and read. And I remember the day of the exams, and because of the conditions, the professors would only put three-four students in the front, and would ask them the question, you know it, you don’t know it, you know it, you don’t know it, and this is how they passed, he asked three questions, those who knew them could pass and the others….And at some point he was tired and told me, “Come here.” He put me in the front and we started talking for one hour and a half and he said, “You will come in the next term.” He said, “Six!” Alright, six is fine, it didn’t really matter to me. And we spoke for one hour and a half, he took my index and put the grade and I didn’t discuss about it. He said, “Come in the next term for a better grade.” I didn’t care about the grade.

And I took my index, I remember other students telling me that I had put them into trouble because they would fail too, it was very interesting. I took the index and went home, I didn’t open it on the way to see the grade and I told my mother that I had passed the exam, “What grade did you take?” I said that I got a six and she took my index, opened it and said, “This is not a six, this is a nine.” I said, “You must be mistaken,” and that was when I got my first nine in the faculty. And this is how it started, I finished the exams of three years in less than one academic year and this is how I joined the Unioni i Pavarur i Studentëve. Back then, Dugolli, Bujar Dugolli was the leader of the Unioni i Pavarur i Studentëve within our faculty and this is how we met and I joined them. And when Bujar won the elections to be the leader of the Unioni i Pavarur i Studentëve that is when he also invited me to be his collaborator and that is how I joined them.

It was a bit problematic for me to join the idea of the peaceful movement because however, it was the time, we didn’t know much about it. Myself, I didn’t have much knowledge about Gandhism until we met, until we gathered as a group, until Albin Kurti came, that is when we started discussing and learning about Gandhism and the peaceful, pacifism, but the pacifism that we knew was the local one of the parallel system, the passive, peaceful resistance, but not the one of Gandhi or something like that. And that’s how we started, I was a member of the leadership of Unioni i Pavarur i Studentëve, I was the only woman there at that time. And then other colleagues joined as well.

We began earlier with the preparations of the protest of October 1, 1997. There was desire, fear, anger and confusion about what was going to happen. October 1 is something that will always remain in my head, the waiting, fear, surviving, what was about to happen? Not to speak about October 1, but I would like to speak about another moment, not for the students, not for those of us who were part of the leadership, I wasn’t part of the organizational council, but I was part of the leadership. I would like to talk about the readiness of all those people to support the students’ movement, to be part of October 1, not October 1 as a date, but I consider it as an institution now, back then it was only a date, only a moment for me, but now it is an institution for me.

The readiness, willing of people to be part of it, to be part of the crowd, of all those students. We chose to wear white shirts as a symbolism, it was not a moment of pride, but of the formation, of the mark, of the tattoo, not with colors but with emotions, things that swallow the moment. October 1 is a life in itself, it is not only a story in itself, it is not only a date, a day, but it is a life in itself. I remember more one day before October 1, that is a great moment for me. When you put your life in…When you put the film of your life backwards and think back of every moment because you know that tomorrow is a big day and you don’t know whether your life will end or not…

[1] A European type of secondary school with emphasis on academic learning, different from vocational schools because it prepares students for university.

[2] By 1991, after Slobodan Milošević’s legislation making Serbian the official language of Kosovo and the removal of all Albanians from public service, Albanians were excluded from schools as well. The reaction of Albanians was to create a parallel system of education hosted mostly by private homes.

[3] In March 1990, after Kosovo schools were segregated along ethnic lines, thousands of Albanian students fell ill with symptoms of gas poisoning. No reliable investigation was conducted by the authorities, who always maintained no gas was used in Kosovo and the phenomenon must have been caused by mass hysteria. The authorities also impeded independent investigations by foreign doctors, and to this day, with the exception of a publication in The Lancet that excludes poisoning, there are only contradictory conclusions on the nature and the cause of the phenomenon. For this see Julie Mertus, Kosovo: How Myths and Truths Started a war. Berkeley, CA: University of California, 1999

[4] Men’s chamber in traditional Albanian society.

[5] In Albanian customary law, besa is the word of honor, faith, trust, protection, truce, etc. It is a key instrument for regulating individual and collective behavior at times of conflict, and is connected to the sacredness of hospitality, or the unconditioned extension of protection to guests.

[6] Lidhja Demokratike e Kosovës – Democratic League of Kosovo. First political party of Kosovo, founded in 1989, when the autonomy of Kosovo was revoked, by a group of journalists and intellectuals. The LDK quickly became a party-state, gathering all Albanians, and remained the only party until 1999.