Part One

Igballe Rexha Jashari: I am Igballe Rexha Jashari, mainly everything of mine connects to Pristina, I mean, as a child, and then my activity continues all around Kosovo. But, as a child, my parents, my father is from the Rimanishtë village, Municipality of Pristina and my mother from Barileva village, Municipality of Pristina as well, both of them. So, my father is Ali Rexha, while my mother is Selime Shala, she’s from the family of Shala of Barileva. I am the first child after seven years of my parents’ marriage.

They got married when they were around 18 years old and I am the first child. And then there are seven of us, I mean five sisters and two brothers. I remembered that for each child, perhaps because we were over seven years [apart], they began with [having] children, my father gave my mother a lira, it was a gift to her. And as well as, you know, other rewards since we were seven children. We were girls first, four girls, and then two brothers and a sister, the youngest sister.

I can say that as a family we were averagely well off. We were well since my father worked, so at first in the industrial agricultural Enterprise, which back then was called PIK [Poljuprivredni Industrijski Kombinat] and later on in KEK. So, he was [working there] until the September 3 strike when he was fired from his job. He worked in KEK. As a first child, as a child in Pristina, I mean, Pristina of course changed a lot since those years together with me growing old (laughs).

I remember how her as a child and I still hadn’t turned seven, my father said, “We’ll go out and get these, we’ll buy something with you,” and it was ‘68. I mean, I am talking about November, November 27, actually the demonstrations of ‘68. And there at the stores, in that street where the old stores were at the Triangle [Revolution Monument] there, so we walked around with my father. He bought me a pair of shoes and when it became evening he said, “You have to go home on your own,” you know, “I’ll get you a cab.”

Taxis back then were horse carriages, so there were horse carriage taxis. And he [my father] put me on a horse carriage there and at where the municipality [building] is now, that’s where the taxis rank was. I feel like I see it even now, so he started to go uptown towards the theater and the stairs there at the Triangle [monument] and climbed the stairs with a long coat. When I went home, my mother said, “Where is he?” I said, “He didn’t come.”

She knew that, I mean, it was the organization of demonstrations and… because my [maternal] uncles were, my uncle was in prison at the time. I mean, imprisoned in ‘64 together with Adem Demaçi and he was sentenced to 13 years. And my other uncle as well, so she already knew that he was a participant in the demonstrations. And they started at home, my [paternal] uncles worrying, I mean everybody, about him being stuck at the demonstrations. My father didn’t come back that night, so because of the police pursuit he was stuck there, somewhere around the Pristina boroughs in a valley, so, until the police withdrew and then in the morning he came back home.

The other part as a child, so we were actually very happy as children, as a family, as good students at school, I mean. I was among the five students in the class, at the Zenel Hajdini elementary school in Pristina, [I was] among the five most excellent students. Six other students were excellent as well. That was a relief for my parents of course, that we studied. I remember the former Miladin Popović library, one we went to often. I…

Anita Susuri: In which neighborhood did you live?

Igballe Rexha Jashari: At Kodra e Trimave. So, when my parents came it was ‘59, when they bought land in that area. The land, much land which was sold as territory later. My [paternal] uncles came there and [members of] my family actually live there today.

Anita Susuri: How do you remember Pristina at that time? While you were a child or…

Igballe Rexha Jashari: With the wooden bridges, so, with rivers, the river floods in neighborhoods. I remember that we went, my math teacher was [living] somewhere near the river here and there was flooding and we went as students to help him clean his house a bit. We went to make a request of our own, I mean, but there was flooding and we went to that neighborhood. Pristina with the small stores, I mean, this part here and with very nice cake shops. The cake shop right near the river that I’m mentioning at the bridge, at the market there where it was and at the time also the Fanoti cake shop as we called it. I mean, I don’t know since how long, but Fanoti is still there and there were those very nice cake shops and my father loved the tullumba and lemonades.

And we, I mean, usually as children at those cake shops, at those… Then as a child I was in my school’s art group and Pristina’s art group. The drawings in the streets, I mean, the ones done by Pristina’s art group were interesting. And then I remember it. There at the theater, people gathered, especially when there was an event when we went out to draw all of that area in front of the theater. The road was narrow back then, I mean, the sidewalks too, we filled them with various drawings as Pristina’s art group. I wrote poems at that time, I mean, poems which were published on the bulletin board at school.

And then I went to gymnasium, the former Ivo Lola Ribar gymnasium, so I was a gymnasium student at that time, and then at Sami Frashëri [school]. So these streets, I mean, hold a lot of memories from my entire childhood. That part now which is in the [city] center around the gymnasium and the part towards the Tre Sheshirat but there was not much movement. Those were good stores, so the clothes were really nice, because the textile at that time was different and also there weren’t many clothing stores, there were a few clothing stores. But the ones that were there had really quality fabrics.

Anita Susuri: I know that, you are a little younger, you might have heard, the [city] center was up to the Grand Hotel and then it was the outskirts.

Igballe Rexha Jashari: It was the outskirts.

Anita Susuri: Do you remember that?

Igballe Rexha Jashari: Yes, I remember, yes. I remember, not very clearly, because as I said until the Tre Sheshirat a little further, I mean. I remember that [I would walk] up there. And that part when the stores opened near Grand and, I mean, that’s how those constructions began in that area, I remember as a child. And then there was the big store here and we called it Uzor at the time, so it was right in that area here in the corner where the assembly is now, the assembly building, but these small [were] stores. A very big store with small [household] items.

That passed. When it was constructed, when the constructions I mentioned began, and that part passed by the Faculty of Economics in that part where the shop is on the other side of the road, the Ministry of Education, and that corner across from it. That store, I mean, when the construction of Pristina began in that part, the expansion began in that area. In school, actually in school since the gymnasium was a better school which demanded engagement, I mean. I, until the fourth year, in the second semester of the fourth year I actually got involved in activities.

Otherwise, I mean, during my time in gymnasium, no, I didn’t engage in something personally, so I, [engaged] mainly with studying and socializing, with those school joys. We were a really, really good class. We celebrated our 25th anniversary after the war, of course, we meet with each other from time to time because a large number of them are here in Pristina. They were, I mean, mainly from Pristina, but there are some of them who migrated, I mean, also people from my class in gymnasium.

Anita Susuri: What did you do back then as youngsters?

Igballe Rexha Jashari: As youngsters, as youngsters we used to go out, meaning we didn’t engage in anything specific but we just went out. There was the korzo as children, back then. I went out very little at that time. I would mainly read, and with the library, and in my free time I admired various sports that I watched. I was a fan, now my siblings imitate me, I mean, when there were football or basketball matches, I mean, I dropped everything and, I mean, I watched them. I was merely curious about them, not that I participated. But I was a fan, I mean, of various sports and other activities.

But the school as a school didn’t have some kind of activities that were carried out during that time. I know that in the Albanian language class, we took special notes for each lesson and the Albanian language professor used to take the notebook, it was for penmanship and those details, I mean, and he would show it in other classes as a good example. Whereas I said that in the fourth year some actors came to ask if there was anyone interested in acting among the gymnasium students, especially the ones in the fourth year.

And I thought I would try for an interview, I mean, with Asllan Hasaj, the theater director, I mean, at that time Skender Nimani as well, who would interview [the ones of] us who went. And they, there was an interview there and [also] that very beautiful reading. So, I mean, I, I said, okay I will accept to continue playing a role. At first I had the role of the mother in Maxim Gorky’s book. So, it was a very interesting role, very [interesting]. Then my own self came to the fore, I mean, an old woman with gray hair, I mean, there in that role. And I also played the role of Hajrie in Halili e Hajria by Kolë Jakova, the book, so these were the two dramas.

With the purpose, I mean, that’s what was said, with the purpose that these artistic groups would go to Albania during that time, ‘79-’80, until the demonstrations of ‘81, and whoever was in these [dramas] had the opportunity, I mean, this was also a reason that I, I mean, went to, to play in those dramas.

Anita Susuri: Did you go to Albania?

Igballe Rexha Jashari: No, because when we had the premiere of Halili e Hajria, it was probably February of ‘81 so there were demonstrations. So, everything in that direction did not materialize.

Anita Susuri: What kind of… what did you organize for Albania? How did you imagine it?

Igballe Rexha Jashari: We didn’t have, I mean, we only had that idealism for Albania, that Albania, being Albanian, meaning Albanian lands. We didn’t have any [idea] about that there is beauty there. All the artistic groups that came during that time, I attended their concerts in the October 1 hall, in the Red Hall, in the Youth Palace, the ones that were in ‘79 I mean, and I went to all of them. I found ways and I attended those concerts. Also, the groups that came, the basketball players, I remember the meeting, I had my brother who I mentioned [was born] after four sisters and my brother is called Shqiptar, and I took him by the hand and we went to Grand [Hotel] where they stayed and I said, “I want to introduce you to an Albanian,” and they, as basketball players, took him in their hands, each one, like auuu {onomatopoeia}, and that, his name.

Now I remembered, I mean, the name, actually my [maternal] uncle who, as I said, was imprisoned and he was released in ‘70. With the fall of Ranković’s system at that time, they pardoned him for the remaining years. And when he heard that my mother was pregnant, he had then said, he had told my [other maternal] uncle that if she gives birth [to a boy], it would be good to name him Shqiptar. My mother birthed my brother at home, not in the hospital, so she called a helper who was referred to as a midwife then. She called that helper to come to the house and give birth at home and he, you know, like… and this [is] a very interesting detail, opened the windows, “A Skanderbeg is born,” I mean, here, and we blessed him [with that name].

I said, my father said, “You name him however you like” I said, “since I hear,” because I was also very young, I was nine years old. I said, “If you listen to me, since our [maternal] uncle said so, we should name him Shqiptar,” he said, “Okay.” But I suffered a lot for this name. Because I am moving from one moment to the other, but I am connecting it with this. In 1989 when my brother went to military [service], and when the [dead] bodies of soldiers started coming from all over Yugoslavia, for me it was a real pain, I mean the fact that we named him that and every morning they call him Shqiptar, it will upset them.

Not a month passed, and they called us and told us that he was sick. He was in Titograd then, I mean today’s Podgorica. And we went with my father, with my husband, so, at that time we went to see him. But he got sick because he was a sensitive child, of course, and when they put him in Morača River, when they put them as soldiers, he immediately caught a cold and… then it passed, but he finished military service I mean.

Anita Susuri: Did he have problems during military service?

Igballe Rexha Jashari: A little. Actually the commander who was there was Croatian and my father befriended him and he said, “Every time you worry just call me on the phone,” so, “and you’re free to be interested in his well being.” We actually went there several times, to visit him and… but he finished military service nonetheless. But during the ‘90s too, he never carried ID with him, I mean. Because he was really at risk, I mean, because of his name.

Anita Susuri: I wanted to go back a little to [the topic of] education, you mentioned that you really liked reading…

Igballe Rexha Jashari: Yes.

Anita Susuri: And there were some books which were forbidden at that time. Did you get the chance to have them? Did you read them? And how did you get them, or?

Igballe Rexha Jashari: Yes, since I mentioned that my [maternal] uncle and my uncles actually were, he, in that part and they had plenty of books. My uncle was an Albanian language professor who completed [his studies] in Belgrade, so at the faculty and he was a language professor in Shkolla Normale in Pristina when he was imprisoned. He was actually the first professor to write in Albanian in the gradebook. He was the first professor to remove the Serbian inscription in the school, I mean, at the time when he worked. Here somewhere, in these old buildings, he lived in this area. Similarly, my other uncle was a professor of English language. But my uncles had these books, these textbooks and we had it easier getting these textbooks, I mean, of… besides the books which were in the library.

My uncle’s son was imprisoned in ‘81, so, that uncle’s son, and he was a recently graduated lawyer and he was employed and he was imprisoned and sentenced to ten years in prison. So it means that there was a part that we continuously had access to, the access actually to these books and these textbooks to read. We constantly listened to Radio Tirana. My mother always had Radio Tirana on at that time. She had a radio which my other uncle brought to her, a radio, those first big radios. The first radios in Kosovo actually. And she always [had it on], I mean and Radio Tirana was a part that we, I mean it was inspiring for us, ideals, work, perhaps how we were brought up, like that.

Anita Susuri: In ‘74, so the Constitution [changed]…

Igballe Rexha Jashari: The Constitution, yes.

Anita Susuri: And there was a slightly brighter period, so to speak, for the Albanians and Kosovo, do you remember that? Did you notice that difference?

Igballe Rexha Jashari: I can say now that people really saw things differently because it was the part who saw that oppression at the time was small. Because [there might have been] some kind of liberation, the university, there were some things. But, compared to the other nations we were constantly oppressed. There was [the issue of] welfare. I said that even my father was employed at KEK since ‘70 and the salaries were good, very good actually, I mean. But, there was oppression, the oppression was in different forms. It was that you were not equal to the other people of former Yugoslavia and no matter how much there was an offer of freedom in terms of education, I mean at that time. Education began, that began, but it was still far from the other places of former Yugoslaiva.

Anita Susuri: So, you mentioned your friends and hangouts during high school. What else remains as a memory from the city of Pristina at that time?

Igballe Rexha Jashari: From the city, the craftsmen, I mean, the blacksmiths, especially the blacksmiths, now I remember as we passed, we were hand in hand with my father and my sister was very curious, who has passed away, I mean, it’s been two and a half years since she passed away (cries).

Anita Susuri: Did you continue university? Why did you choose this field? How did it come to that [decision]? It’s also the year when the demonstrations began. Tell us all that you can.

Igballe Rexha Jashari: I chose the Faculty of Economics because I was, besides the part that I mentioned about being inclined towards culture, towards language, which was almost like genetics for us, I loved mathematics, I knew mathematics, I was fond of it and of course, that the gymnasium gave you the opportunity to learn mathematics better. I did not have the interest to be, I mean, in medicine or something. I mean, those faculties, but we were in Economics and we were a large number of classmates who actually went to [study] Economics. It was ten or 12, I mean, from our class who enrolled in [the Faculty of] Economics. And that was the starting point for me to continue at the Faculty of Economics.

In ‘81 where, I mean, a little while before the demonstrations there was a group of students who were actually, they worked in different groups, I wasn’t organized with some groups, I mean, I only did my own thing at that time. But I was also invited to the students dormitory, which, I mean, was interesting to me. It was the first and last time that I went to the dormitory actually, with those friends back then. And they told me that they were working on something in that direction.

And since I heard that I contacted my [maternal] uncle’s son, who I mentioned was imprisoned, and I told him this and that. So, “Something will happen in Kosovo during this time.” He said, “There will, but not now.” So, “There will.” But he said, “Not now. It’s being worked on.” Of course, he didn’t say he was [working on something] himself. But, “It’s being worked on. There are different groups that are working in that direction and, because some things are bad for us” and the things he explained as an older person, of course.

I remember and I was in the amphitheater when they came and they said that, I mean, it was in the students canteen, that it started, it blew up. In the amphitheater, there was a person and I don’t remember who it was, I mean, some people say [it was] Ali Lajçi, but I don’t remember the person. But, I know that the amphitheater door opened and, I mean, they said, “You go out as well and stand up and…” and then there was the participation on the dates of the demonstrations, and I, my sister was a first year student in Sami Frashëri school then, I mean, as well as Ivo Lola Ribar gymnasium.

And, I mean, when the April 1 demonstrations [1981] started, I was actually at home because I didn’t know, since I wasn’t part of those groups, I wasn’t… but, since I heard that it blew up there, that’s when I immediately got up and my sister who was only 15 years old at that time came after me. Of course, I tried, I mean for her to go back home but there where the assembly [building] is, that’s where we saw that the protesters were coming, the demonstrators actually, so, and we joined them there.

I sent my sister away to the market once again and I accompanied her so she could go home, but she still joined me that day. So, we stayed there, right in front of the loudspeaker, so in front of the words that were said, we listened until the police intervened. We entered one of the buildings where Kraš was located before, where ÇIK is now, not even ÇIK is there anymore (laughs). The store, where the flowers are, where the flowers are placed in that part across from the Ministry of Culture there, it was a store, ÇIK, if somebody [remembers], that’s how we oriented ourselves.

We went into that entrance, I mean, of the building together with my sister and a few other people. At first they just locked us in, so in order for us to not go out they threw tear gas and for us to not go out of there but since the screams were loud and the people seemingly [were loud as well], so they said, “Go out” but they grabbed some of the people there. And we ran down the road, with, the tear gas [affected] my sister, so, of course, it worsened her, and I said that she was a burden in that case, I mean, for me because I had to, I mean, hold her and not let her go, where we saw the policemen.

After a few hours we arrived home, I mean, that night. But, my sister continued organizing the students the next day, so she was like that since she was 15 years old. From the police persecution they sent them somewhere further from the Shkolla Normale above Gërmia, in that area. And she had a flag in her hands and that’s how she wandered and she didn’t come back for one night, she was actually stuck there.

And there was the risk of being expelled from school for her. There was Professor Ali Ahmeti, who passed away, who was a very, very good Albanian language professor. [He was] the head teacher who actually saved her from expulsion because she was the best student in school. She was head of the class, I mean, all her grades were fives and [he helped her] to not be expelled from school. I don’t know how he justified it, but I mean, she got away without being expelled from school.

Anita Susuri: When you went back to your family, were your parents worried? What were they like…

Igballe Rexha Jashari: Very, very, much, I mean, our mother came after us first, so, like, “Don’t, don’t, don’t go,” but she went back. Yes, they worried a lot. My father didn’t know because he was at work, but my mother was very [worried]. And, “Don’t, don’t, don’t, you don’t have to,” like a parent worries, of course, they worried a lot because we were actually young. I was young too but my sister especially was younger than me, she was five years younger. Of course, she was very young.

Anita Susuri: What else did you see those days? Was there violence?

Igballe Rexha Jashari: Yes, of course, there was violence, absolutely. And there were some batons, I mean, like that, but of course, I mean, there was violence and everything. So there was a gloom in Pristina because of everything, of course. So that was a starting point of the years, actually ‘81. There was a calmness more or less until the years ‘88-’89 but that was actually a start for all the following developments.

Anita Susuri: How did you notice this after… after the demonstrations the diferencimi also began, imprisonment began…

Igballe Rexha Jashari: Absolutely.

Anita Susuri: What do you know about that?

Igballe Rexha Jashari: I also remember that [some of] my friends weren’t at the university. Some of them were absent, they began missing [classes] and, I mean, they were imprisoned. I realized that they were groups, I mean, some of them from there, friends from university. Of course, that my [maternal] uncle’s son was imprisoned, I mean at that time, and he was sentenced to ten years. There were imprisonments of many groups, there were friends too, actually from my friend group too, of [my] sisters[‘s friend group], my brothers’, I mean who were imprisoned.

So, it was a difficult situation for those who had that fate, because it wasn’t [the same] for everybody, I mean. But, there was an increase, of the whole situation. Compared to the time when my [maternal] uncle was imprisoned in ‘64 there was an increase of the masses, so it was different in ‘81, for example. It was different. I am saying, for myself, I mean, I didn’t hesitate to speak for a right, I never hesitated, not even among friends. So, there were different ways where you understood who stood where.

I remember a colleague from Struga, he was [studying] at the faculty and when he more or less understood that it was a few of us, it wasn’t just me and like that, I mean, continuously, “Your spot is safe here in the amphitheater,” “Where mud seems sweeter than honey.” And there were some expressions that… at that time I played in some skits as part of the Drita association of the Faculty of Law. I participated, I mean, once.

Ehat Musa was the singer who used to come from Struga and I played in some skits at the green hall in the Palace of Youth and I more or less continued with that fach and that grouping of people in various ways, there was Naser Gjinovci, I mean, and Aqif Mulliqi who carried that friendship and that was a part, I mean, joyful and a time when I participated [in the skits] during my studies.

Anita Susuri: Were they like amateur groups?

Igballe Rexha Jashari: Amateur groups as part of the faculty, as part of the faculty, yes.

Anita Susuri: I wanted to ask you, did you have professors from Albania?

Igballe Rexha Jashari: No.

Anita Susuri: You didn’t.

Igballe Rexha Jashari: We had professors who were Sami Peja in Goli Otok, as well as Hajrullah Gorani. Professors who suffered in prisons and we as students, especially Hajrullah Gorani, during break in-between classes, he held meetings with groups of students and he talked about those struggles, but also about Albanian in general, Professor Sami Peja as well, he passed away. So they talked about that part and how we should be, so Albanians should have better conditions, how to study, to advance. As Albanians at that time it was…

Anita Susuri: Did you know the professors from Albania that they sent away? They didn’t allow them to come and give lectures.

Igballe Rexha Jashari: I don’t think the Faculty of Economics had any, so there were professors from there in the Albanian language and medical [departments] and at the Faculty of Medicine, I don’t remember there were [professors from Albania] in the Faculty of Economics, no.

Anita Susuri: You mentioned that during your studies you were engaged in cultural activities, did that continue, how long did that last?

Igballe Rexha Jashari: A little, I mean, maybe for one semester, during that time, it was one semester.

Anita Susuri: Why didn’t you continue?

Igballe Rexha Jashari: I don’t know, maybe my friends, the summer break and I didn’t join them the next year, like that. So, that was, they were… maybe I grew up a bit and (laughs). My parents didn’t want me to be in, I mean, in the theater although I was accepted. So, they accepted me at the National Theater and I had signed my contract, how to say, so after a week they made it possible [to sign it]. But, my mother said, “Don’t ask your father at all because that’s not our wish [for you],” and I mean I gave up completely on that thing (laughs).

Anita Susuri: When did you first start working after finishing university?

Igballe Rexha Jashari: I began in 87 in Rilindja. Actually I still had one or two exams to finish. I was at the National Library studying together with my sister Shukrije Rexha who was [studying at] the Faculty of Medicine, and at the time we studied together. She was preparing for her exams and she herself was a, I mean [she] always [took] different initiatives and ideas, that’s how she was.

She had seen the job opening at Rilindja. She was the one who had seen it. And she told me, “You have to go there and apply for this,” I had a journal, so I had a journal and I consistently wrote there, I continued to write, I continued to draw and the drawings of my other family members, I continued with that. And she, knowing that part of me I mean… she said, “You have to go to the interview in Rilindja, I said, “No, I won’t go to Rilindja.” Journalism and economy were something, “You have your fate. Regardless of whether you’re insisting on economics, you have your fate. You have to go to the interview.”

That day the interview was at 12:00, and I got up for the library at 11:00 and went to the interview at Rilindja. When I went in there was a big group of people who, I mean who went for the interview. Actually the interview was in written form. So, I did the interview, there were questions regarding various news starting from the federation back then, the assemblies, events, sports, music, different fields, which I more or less knew about. And they said that the results from the written interview would be announced after four-five days.

There they asked me, “Who is it? Who is the person who will bring you here and support you,” because back then it was just like it is now. There was no way to work in Rilindja if it’s someone who didn’t have anybody to support them. I said, “No, I came here by myself, not even anybody knows except for my sister,” “No, you don’t stand a chance.” They made the announcement five days after and I didn’t go that day. I didn’t believe it at all to be honest, I went the next day. And I saw the list of the 20 people who were accepted, I was in that list too.

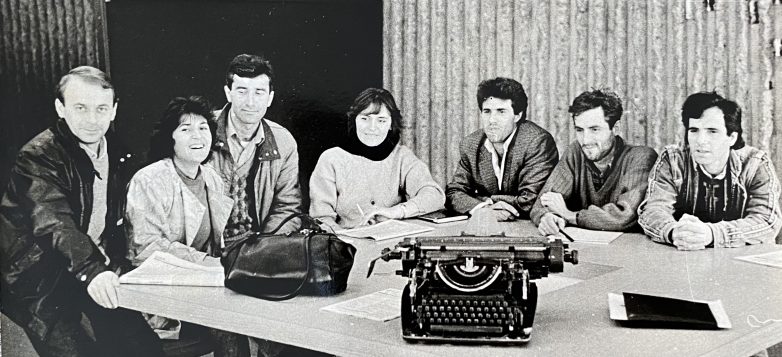

They began because, they began with the chronicle Pristina, there was a page about the chronicle of Pristina at that time in Rilindja. The editor Esat Dujaka who up until recently was at 21, working at the television [broadcasting channel] 21 and the editor Shefqet Rexhepit, it was both of them. Initially with the chronicle of Pristina since I was among those [who dealt] with economy, I began to follow the enterprises during those years ‘87-’88 until the other part started, the other time period. Later on I also started to follow the enterprises that were in Pristina, especially the productive, service, and trading enterprises. And until that began in ‘89, the ‘90s which was a short period, it actually wasn’t long.