You know, very, I don’t know what did they do, the things were all over the place. The machine, for example, was ruined, an old stove was taken upstairs, you know, I don’t know how did they carried them, those things. There was a lot of disorder in the building, empty apartments, without anything inside them. They didn’t touch the pictures and some documents because, after all, it was a building.

And one, one resident there, she was Dalmatian, older, she didn’t have anywhere to go, so she stayed there. She told us that they brought the truck at the entry, so we couldn’t see what they took, what are they loading. Cassettes, we had a lot of video cassettes, all with serious music, recorded, different kinds. My husband was fond of classical music, he used to record instrumentals, orchestras, of different kind. We found those in another building. So, unexplained things happened, I don’t know, I don’t know.

But it’s interesting how one remembers everything he had, it happened a few times, people don’t remember everything they have, but if the things are missing… It was a bit funny. I made the list of everything that was missing because I knew what I had in my cabinet. Only notes, notes, my songs and so, I, I threw them behind the cabinet, there was free space but couldn’t go down further, I found them there.

The research on Kosovo through its creative artists aims to gather life stories of personalities in the field of literature, visual arts, cinema and the theatre. Testimonies straddle linguistic differences and convergences, giving a unique view of the struggle that different generations of artists have had to face in order to emerge on the public scene.

Pranvera Badivuku

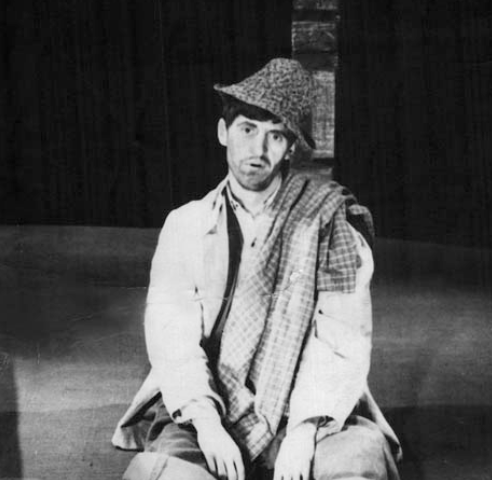

ComposerAdem Mikullovci

ActorI don’t know, don’t know, when I finished [high school] matura we had a big discussion in my family about what I will study, and many suggestions were given. From, I don’t know, physics, mathematics, astronomy, languages… geography and what not. My father would say, ‘Lawyer, the pig should become a lawyer, his mouth never stops grinding like the grinder’s funnel, and he will put everyone to shame.’ Whilst my late mother would say, ‘Doctor, doctor. He has poor health, perhaps he will find himself a cure.’ Even, even, and I am sure about this, the cleaner, the shoe cleaner in the mahalla [neighborhood] engaged in this conversation about my studies. [He said] ‘Professor, become a professor and you will be a master for life.

Sokol Beqiri

Visual artistI chilled for ten years at the coffee shop here. I followed through few generations, now Era and her friends are the youngest generation… nothing, I took walks, sometimes I… I want to tell you two stories. One day, when my older daughter Toska was little, my father asked her, ‘What does your father do?’ And she was wondering what her father does, ‘What does your father do?’ He was trying to help her, you know, to say a piktor [painter], and he said, ‘Pi – pi – p…’ She said, ‘Pijanec’ [A drunk] (laugh) and the other one, I am telling you what my second daughter told her teacher, that’s what I did ten years in a row. When her teacher asked her, ‘What does your father do?’ She said, ‘He has fun.’ (laugh)

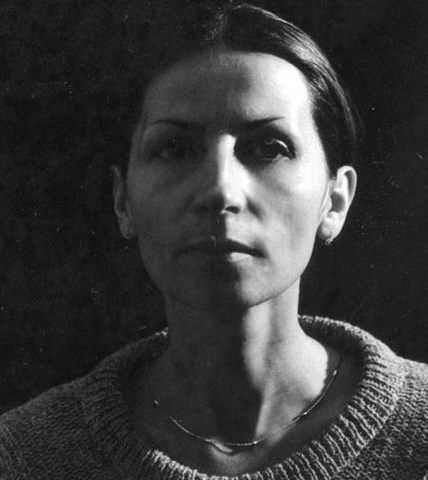

Melihate (Meli) Qena

ActressThe evening stage at that time… Begolli prepared the Jom Talent se jo Mahi [No Joke, I am a Talent], which constantly dealt with, with the problems of the society, and talked about our daily life in a sort of cynical way. [The show] had an extraordinarily big audience. In the Puppet Theatre, we tried to organize everything that was lacking in school life, concerts, masked balls. We somehow tried to fill the emptiness that existed in schools. So, the theatre at that time wasn’t simply a theatre. It was a garden, entertainment, education and everything else. And I hope I was successful in that job.

However, we didn’t let people be swallowed by the sadness that existed everywhere, in the streets, at home. Here there was a kind of oasis where they could feel freer, more… see a different world, maybe live a little of that fairytale, that illusion. It was a little bit of freshness for those people.

Zeqirja Ballata

ComposerWhile being in Maribor, in Slovenia and part of the Association, I travelled, I travelled by all means, you know, regardless of whether I had a car, regardless of whether I had savings, because you didn’t, you know, we had means, there was no need to think about savings. I went to festivals […] There are many festivals, many activities, they tried to have activities in other centers too, yes… For many years I was present, even when my compositions were not played, but I went to follow the festival. That was refreshing, their intensity was greater compared to ours and our conditions at the time. Therefore, even the inspiration was greater. Yes, even the inspiration, the innermost inspiration, and we tend to say that one needs solitude to create. You know, there is something true about that. You know, silence, solitude.

Elizabeth Gowing

WriterSo, it’s called Travels in Blood and Honey. Becoming a Beekeeper in Kosovo. So this one really tells the story of, from I first arrived in Kosovo in 2006 to 2008 like when we left Kosovo, the last chapter is us leaving Kosovo. When we thought that, you know, Rob had a job back in England and we thought that our time in Kosovo was coming to an end. Little did we know (laughs) that was just the beginning. But… that’s, that’s, it’s got a very different feel in my opinion because it’s about becoming a beekeeper but it’s also about learning not just beekeeping. But, learning Kosovo’s history and its traditions, its food. You know, it’s got recipes in the book for what to make with the honey.

It’s a very sweet, very lyrical book. I think it’s kind of, it’s a lot about the landscape, the countryside, the villages, and, and, it’s kind of a love story about me, you know, falling in love with Kosovo. And, and, so I, you know, I love that book because it’s, it really tells that, that journey. But, I remember there was one review of it that said it was uncritical of Kosovo and I suppose that’s true, I mean, I didn’t want to be critical, and, but, also I perhaps hadn’t got, you know, deep, I hadn’t met the community in Fushë Kosovë to see some of the problems and frustrations. So, yeah, it’s a love story, when you’re in love with someone, you’re not critical (laughs).

Rafet Rudi

Composer and Conductor… it’s not because of Paris or because of that contact that I got to hear only good orchestras, or only good artists, or attended only great cultural events, but from that position one observes more closely the flow of things here [in Kosovo]. I started understanding better, clearer, seeing the value in Albanian music, or the values that you have, your personal values, right? You know, when you’re a bit farther away, you know that distance, let’s say even physical distance, but the cultural distance of the environment mostly, you understand better the environment where you will go back.

That is your primary environment, right? And I have understood it better and that is quite important, developing and following the standards that exist in a center of culture. First, researching, understanding, experiencing those standards, that makes you better, so that you to launch and to try to preserve those standards in the less developed environment that we were at the time. You don’t see those standards if you go to Paris only once, for example, right? You attend a concert and you come back and you think that is how it should be done. No, when… only when you experience the rhythm of a big cultural center.

Sevime Gjinali

Musicologist/ ComposerMy father…. Look, at that time nobody was writing, doing musical notation, nor there were notebooks with scores. He was a rhapsodist himself, he wrote the lyrics and the music on the spot. But nobody notated them, there were no means to record them. […] And he decided about my education, that I become a musician, that I study music… at that time there weren’t, it was somewhat unusual for a woman to go to music school with a violin. The kids in the street threw rocks at us when they saw us, because I was going to music school carrying a violin….For a woman it was a bit unusual.

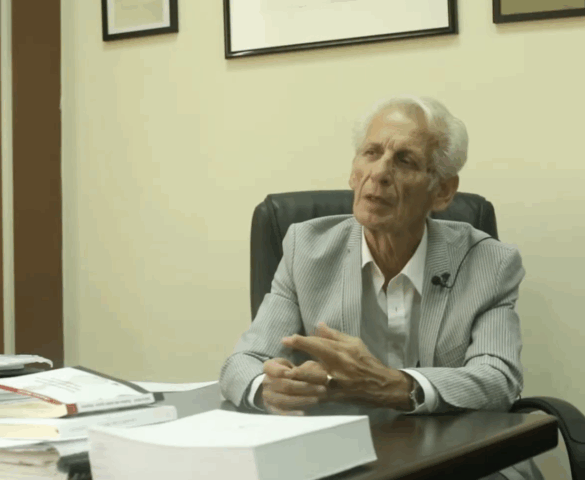

Agim Vinca

Professor at University of PristinaMy brother, who was the class monitor, told his colleague, […] ‘Give them some math homework for the summer,’ and he gave us some typewritten sheets. And I and my classmate, […] with whom I finished eighth grade, Xhelal, we worked during the whole summer in the garden, under the shadow of the apple tree, he was a little better than I, the whole summer long, July, August until September, we split the math [homework], once each of us on our own, then we checked whether our results were correct. Well, we did it once, twice and three times. We did it and we thought, but alright, let’s say we pass the exam, but what are we going to do if we don’t? If you failed a class at that time, it was a big shame, you could not show your face in the village nor anywhere else.

And we, with our then childish mindset, took a decision […] if we failed a class, first, we would kill ourselves, we would commit suicide; second, we would kill the professor with a knife, because we had no gun, and we could find a knife, we didn’t have a knife either, but we could find it, in our mind we had three alternatives; and three, this was a little easier, we would escape to Albania. My birthplace Veleshta, […] it’s twelve kilometers from Struga. […] We would take the ship from Struga, in the port, travel for two-three hours, it was a beautiful journey […] And we would go to to Saint Naum. […] We would play, sing with friends and so on, and the border was near there […] We were not allowed to get closer to it, but we looked at it from a distance and thought that in case we didn’t pass the math exam, there were three options: suicide, murder and escape. We thought that we could escape to Albania from there, because for my generation and the generation before me, Albania was a kind of paradise and every youth of that age dreamt of escaping to Albania, all of them.

Murat Bejta

Educator[Tirana, 1979] The one who followed me or who accompanied me, pretended to be a professor of Albanian Language. But while I was talking to him about different topics, I became convinced that he was not a professor of Albanian Language. […] While eating breakfast one day, I said that he was not a professor of Albanian Language. ‘How do you know Murat?’ ‘I know because while I was talking to him, he said some things, some thoughts, some viewpoints that do not fit with his claim that he is a professor of Albanian Language.’

[…] Oh, yes, he said he was not of a professor of Albanian, but of Chemistry, not of Albanian, but a professor of Chemistry. ‘You told me you were a professor of Chemistry, therefore allow me to ask you a question. Can I ask you a question, please?’ ‘Yes, Yes.’ ‘Even during high school, but also later in life until today, I heard that carbon is two valence, even today I don’t know what means two valence, and why two valence?’ ‘Forget that professor, forget it…’ Everyone burst into laughter (laughs), and they were persuaded about what I said.