Part Two

Aurela Kadriu: Can you tell me, given the fact that you went to Belgrade as an Albanian in ’64, how were you treated as an Albanian in the School of Arts, that’s a more specific setting?

Adem Mikullovci: Look, the Serbian nationalism and chauvinism existed even before, but I had a good time, there was no different treatment except by one professor. One professor told me, “When you get the diploma, there will be ‘The Theater Academy of Belgrade,’ printed on it. I don’t care what language you will use in other plays, you have to know Serbian very well.” I can say that this was the only moment, a kind of threatening of that sort. Otherwise, there was absolutely no differentiation.

And look, you are young and don’t know, the further from Kosovo, Serbs don’t care about Kosovo. Belgrade doesn’t care, they really don’t. My friends don’t care, God forbid! They are not loaded like those who are closer to us. There is a saying in Serbia, “Što južnije, to tužnije” The closer to the south, the more painful. You know, the difference is very big.

Aurela Kadriu: Were there any other Albanians studying in your generation?

Adem Mikullovci: There were no Albanians in my generation. Faruk Begolli[1] and Enver Petrovci[2] came after.

Aurela Kadriu: Was there…Everyone I speak with always speak about a kind of solidarity between Albanians, new students who went there to study were welcomed…

Adem Mikullovci: There was solidarity, there was solidarity…

Aurela Kadriu: Among students…

Adem Mikullovci: Among Albanian students. There was also an association, I don’t remember its name, an association of Albanian students but I wasn’t part of it because I didn’t have time because I was taking interpretation classes in the morning and then in the afternoon I was taking directing classes. Then we had, we played in many theater plays because Bekim was helping me engage in theaters in order to get a per-diem. I played small roles here and there, one sentence here, one there, one statist here, one there. And I didn’t have much time to deal with that. But, the association existed there and they had their own program. They criticized me a lot for not becoming part of it but, I really didn’t have time so I remained out of it.

Aurela Kadriu: What kind of theaters were those small ones in which you were engaged? Can you tell us a little?

Adem Mikullovci: There was the so called Yugoslav Drama Theater, there was the Atelier 212, the Belgrade People’s Theater. Here’s a nice story where I was present, but I didn’t experience it. There was this play, Richard The Third of Shakespeare, a friend of mine, a colleague of mine had two roles. His first role was just passing by the stage, and his third act had text as part of it. He came to the first act and the director shouted at him, “Idiot, maniac, how can you walk like that on stage? Get out!” And he expelled him.

The rehearsal continues and then he comes with the third act on his role that contains text and he does it very good, he plays it very good. The professor says, “Where is the idiot of the first act who didn’t know how to walk on stage?” Somebody said, “Professor, this is the same idiot, the same idiot from the first act.” It was a nice story, a lot was spoken about it in Belgrade at the time.

What is interesting from that time, even though it is not related to me at all, is the time when Mbledhësit e Puplave [Feathers’ Collectors] movie was being shot, the movie of Bekim Fehmiu. It became a very hot topic in Belgrade at that time because they were against an Albanian playing that lead role, because it was exactly in the Yugoslav Theater, Bata Živojinović[3] was opposing it. There was the very famous singer and very good actor, Olivera Katarina…They didn’t want Bekim Fehmiu to have the main role. The director was very insistent that Bekim played that role. But, there is a scene where Bekim slaps the actor, Olivera Katarina, I don’t know if you remember?

Aurela Kadriu: Yes, yes, yes, yes…

Adem Mikullovci: Eh. She stopped the shooting after that scene and said, “He hit me for real.” And she sued Bekim and kept accusing him for days in a row, newspapers wrote that he had really slapped her. Bekimi only responded once to that, I will never forget it, “It’s true, I slapped you with all the strength I had, but in the role of Bora, within the role, because I have no idea who you are in your private life.” And her mouth was shot, because you either play a role or you don’t. You either play it with a full heart, soul and emotion, or don’t do it at all.

Aurela Kadriu: Were you close to Bekim?

Adem Mikullovci: I was very close to him. I hung out with him a lot. He helped me very much. While we were working for the theater, for two-three years before he died, he came and we hung out in front of the theater every summer, we talked and walked together. People came wanting to take photographs with Bekim but he never allowed that, he didn’t want to be photographed. It happened one day that a couple together with their children knew me because of the TV shows and the man came closer to me, I was alone with Bekim, he told me, “Baca[4] Adem, can we take a photograph? We are from Switzerland and we love you very much…” He started praising my movies and so on.

I wanted to make a point to Bekim that we should take photographs with our fans, I said, “Yes, of course! Why not?” I took the photograph, one pose, another one, and then I hugged his children. And the man put his hands on the pocket, took ten euros from the pocket and said, “Here, take it!” I was like, “Put them back in the pocket! May nobody see you!” Bekimi was two meters away looking at us. He said, “Take them, take them because you artists have no money.” I said, “Take that money away, don’t..” When his wife took it in her hand and said, “Take them, uncle Adem, because we also paid ten euros to take photographs with the monkey in the beach.” (Smiles)

I went closer to Bekim and he said, “Will you ever ask me to take photographs again?” I Said, “Never.” And I never asked him to take photographs with fans again.

Aurela Kadriu: Did he ever speak to you about the occasion with Olivera Katarina?

Adem Mikullovci: No, no, no. Those were higher issues, they were part of the movie set, I went to the Academy and I had no contact with him at all. But, I followed him with full attention. We are interesting, when Bekim passed, when he committed suicide, there were several TV shows about him, they would invite people who didn’t work with Bekim, who didn’t know him but only watched his movies. They praised him without ever having even had coffee with him. We are interesting people.

The same thing happened… Nobody invited me and I never had the chance to speak publicly about my collaborations with Bekim, how much I used to hang out with him and how I knew him. The same thing happened when Shani Pallaska passed. There was this TV show, it was broadcasted from KTV, Alban Morina, Fatos Berisha and I don’t know who else was invited…Shani Pallaska passed, they spoke about him and all they said was, “I saw baca Shani in that TV show, I saw him in this theater play, I hung out with baca Shani, he was an actor…” But none of them worked with Shani!

Leze, Xhevat when he was still alive and I were the ones who actually worked with Shani. I played some theater plays, he was my direct partner and for days and nights I spent seven to eight hours a day with Shani Pallaska. I even know how Shani Pallaska breathed. He invited guests to go there and say, “I have seen, baca Shani was good.” We don’t know how to value people. We have to know how to make an assessment before inviting someone to talk about something, who knew him, who collaborated with him. His close collaborator should speak about him, how he saw him.

Aurela Kadriu: Until when did you stay in Belgrade?

Adem Mikullovci: Yes, from ’64 to ’66.

Aurela Kadriu: When did you return to Kosovo, what…

Adem Mikullovci: I had the scholarship, do you know what it is?

Aurela Kadriu: Yes, yes.

Adem Mikullovci: I received a pretty high scholarship from the theater, it was equal to the salary of a beginning actor. I returned to the theater and got employed right away. In the first year, a full year passed and I was not given any role and I started losing my self-confidence, would anybody ever give me a role or not? Until my professor from Belgrade who knew me from the Academy came and gave me a good role. Than I waited for the critiques to come out for a week, because they praised me for my role, all my colleagues…I was waiting to see what the critics would say about me but no critique come out. Rilindja[5] wrote about it after over a week, they were praising and criticizing the play and in the end, “The roles were played by this and that…” And in the very end, the very last sentence, “And, Adem Mikullovci.” Nobody started off their theater career worse than I did.

Aurela Kadriu: What was your role in this play?

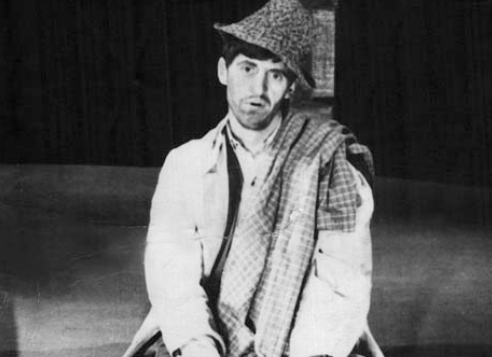

Adem Mikullovci: It was the Po shkoj për gjah [I Am Going Hunting] theater play, of Georges Feydeau, a French comedy writer, that text of his was very famous. I played Leze’s nephew who was a hooligan. It was a really good role, maybe I wasn’t all that bad, I cannot say that I was good, that is disputable. But, that is how the first play went.

Aurela Kadriu: How did the theater work at that time?

Adem Mikullovci: Eh, how the theater worked at that time, unfortunately…Look, you are young and don’t know this but there were several festivals around Yugoslavia. At that time where we…especially during the time when Azem Shkreli was the director, we were maybe the best theater in Yugoslavia. We had plays delivered in festivals in Ljubljana, Zagreb. There was a great discipline in the theater.

There was the drama festival organized in Novi Sad at the time and only five theater plays from all over Yugoslavia were qualified for that festival. Sarajevo couldn’t make it to that festival, neither could Zagreb, but we did and Muharrem received an award for directing, Melihate received another one for her role because we had great discipline. It was clear to us that we had to be at the dressing room one hour and a half before the play and we had to be dressed one hour and a half before the play.

Because I see young actors, I saw them when I was playing my stand up comedy, they came running, undressing half their way through the corridor to wear the costume and go on the stage. That could never happen to us, there was no way it could happen to us.

Aurela Kadriu: Did the theater have any resident actors?

Adem Mikullovci: Of course there were, there were forty actors, 35-40 actors. We delivered plays every night, every night except Mondays. And there was a period for example, when I played four main roles in four different plays and I delivered plays four time a week. There was no room to engage in films or anywhere else because of the repertoire. And we stood behind the maxim that no matter what happens, the play has to be delivered. And it happened, I wasn’t in the theater at that time, but before I came to the theater, the daughter of Masar Kadiu, our valuable actor, passed, he buried his daughter and came to play his role in the evening.

There was no way a play would be cancelled. We were on rehearsals for the Hamleti në farmerka [Hamlet Wearing Jeans] play, a modern play with Çun Lajçi[6] when we received the news, Azem told him that his mother in Rugova had passed. Çun started crying and so did we, we stopped with the rehearsals and Çun went to his mother’s funeral. The director told us, “Come to rehearsals tonight after lunch, without Çun, we can still rehearse, improvise, repeat the text until Çun comes back from his mother’s funeral in Rugova.”

And we just started the rehearsals at around 7PM when Çun came in. It had rained and he was wet, he was sad, he seemed even smaller than he was, “What happened, Çun?” He said, “We buried my mother, I went home, it was empty, my mother’s clothes and stuff. I couldn’t stay home anymore, that is why I decided to come to rehearsals.” And he came to rehearsals. We were that committed at that time. And Çun made us cry again for his love, his commitment. This is what my theater was like.

Aurela Kadriu: What was the audience of the theater at that time?

Adem Mikullovci: The audience was such that it was a surprise if a play wasn’t sold out. We had plays that weren’t sold out and we only played them five-six times and then removed them from the repertoire. The room was always full and there were five hundred seats. Now there are three hundred, but back then there were five hundred seats and the room was always full. So, there were cases when a play was sold out one month before because people could see the schedule and it was sold for the whole month. Let’s say there were five plays for one month and they were all sold out. There were no tickets left, no tickets left.

We didn’t have today’s televisions and coffee shops, we didn’t have the kind of parties you have today. The theater was an event in itself. I know that people sewed clothes for a theater play premiere. They bought new clothes.

Aurela Kadriu: Did you ever experience any provocation or intervention during a play, given the political situation of that time?

Adem Mikullovci: No, there weren’t. We did have provocations, I have to mention the Halili e Hajria [Halil and Hajrie] play, this was in…I don’t remember the year, when your national renaissance started, when we started raising up and the actors could play in the theater. It was a scene where the Pasha was played by Shani Pallaska, Ragip Hoxha and Malogami and they sentenced Xhevdet Lila, Shaban Gashi and Isa Qosja, the director to death, to slaughter. And look, since the text was like, when Shaban Gashi was saying, “Because we can’t give the Albanian besa[7] to a foreigner,” you could sit and smoke, because the applauses lasted that long.

It even happened once, I don’t know where, I guess it was in Mitrovica, a person came up on the stage and was directing the audience when to applause. In the end, Shani, Ragip, and Mala were afraid to go out because they were afraid that somebody would really attack them, because the let’s call it this way, national feeling, was so intense.

Aurela Kadriu: What kind of city was Pristina when you returned from Belgrade and decided to live here…

Adem Mikullovci: Pristina was a city that, God forbid what they have done to it, they have cursed it. I am not from Pristina, but there were two rivers flowing through the city, there were shops, old shops, old pastry shops, terzi,[8]watchmakers, different craftsmen. It was a town, it was exactly a half-oriental town with many pastry shops but with very few coffee shops. People were mainly passionate about sports, cultural life. This is how we were.

Aurela Kadriu: Which was the first neighborhood in which you lived in Pristina?

Adem Mikullovci: I don’t know how it is called, near the triangle[9] {points towards the window}, near the monument close to the municipality, I was renting there, my first landlady was a Serb. I rented for two years, I changed houses until….Because back then the assembly would give apartments and since I became famous as an actor, people started valuing me as an actor, I don’t know if I was to be valued really, but my turn came that they gave me an apartment. I got my own apartment.

Then I sold the same apartment that I got from the theater and built a house in Bërnicë. I added some more money and built my house in Bërnicë. This is something that cannot happen to the youth now, who will give you a three-bedroom apartment today? Nobody! But they gave it to me back then.

Aurela Kadriu: Was this a period when you were also politically engaged or am I mistaken?

Adem Mikullovci: No, you are not mistaken. Look, when you say politically engaged, there is one thing I would like to explain, I don’t think I deal with politics because I am not a politician. I am a member of the parliament. A member of the parliament elected by the people who trusted me with their votes to be their representative. I don’t know how to govern or other things. I am only engaged in the parliament, I give my contribution there as much as I can.

I also belong to the generation of the parliament that announced the constitutional declaration and the constitution of Kaçanik.[10] This is also an interesting story in itself. I was so overworked with plays and we were also shooting a movie at the same time, in fact it was a TV drama, and I didn’t even know that I was on the voting list, that I was being voted as a member of the parliament. I was elected but I never went to meetings. I didn’t attend the first two-three meetings until they came from the parliament and told me, “Come, because you are a member of the parliament.” “What am I?” “One of the members of the parliament.” “And what am I supposed to do there?” “To speak about theater, culture and arts…” So, I went to meetings from that point on.

Given the communist system, the names of the elected were known in advance and they all had two candidates. It was me and another one for the same position, for the position of the member of the parliament for culture, it was only the two of us. And now in the parliament they are telling me that I had around six hundred thousand votes, so many votes, I beat the other candidate (smiles), and they elected me. I didn’t even know that I was elected a member of the parliament.

Aurela Kadriu: How was this part of your life? This detachment from art?

Adem Mikullovci: To be honest, it wasn’t good. As I told you, in the ‘90s I engaged as a member of the parliament with the goal to open another theater, the muppet theater, and later we opened the Dodona theater. You know? I wanted to cultivate culture. But there were demonstrations, murders, detentions. It all went to hell, I realized that there was no room for culture nor theater and so I got involved in the flow of events of that time, in collaboration with professors who told us what to do, they helped us, Gazmend Zajmi and the others.

Aurela Kadriu: In the meantime, did you continue being part of the theater?

Adem Mikullovci: Absolutely! Because look, there is a difference. My mandate lasted for one year and I didn’t get a cent from the parliament. We weren’t paid. We were paid from the places where we were working. We didn’t get any per-diem nor anything from the parliament. Now the salary in the parliament is very good but this is how it was back then.

Aurela Kadriu: How was the theater in the ‘90s? Was it closed?

Adem Mikullovci: No…The theater was closed later. I don’t know in which year, in fact, the theater was never closed, it continued working but then there were the violent measures. There came the Serbian director, he enforced the repertoire and a whole different regime. But in the ‘90s I still played in my theater plays, there were even cases, two-three times the plays were cancelled because I was busy in the parliament, with meetings in the parliament.

Aurela Kadriu: What did you do when the theater was closed?

Adem Mikullovci: I never went back to the theater. Because those of us who declared the Kaçanik constitution in Kaçanik, who were members of the parliament, we fled Kosovo. We went to Slovenia, first we went to Croatia then to Slovenia so that the parliament could continue taking decisions. And thanks to decisions of the parliament, of the July 2 as we call it, Kosovo continued living until UÇK[11] showed up, until the war broke…

Aurela Kadriu: What were these decisions?

Adem Mikullovci: The constitution…Free elections, the referendum for independence, decisions to maintain the health and education system in private houses.[12] These were all things that had to be managed, and they were all managed by the parliament of July 2. We did everything from Slovenia. The temporary government in exile with Bujar Bukoshi as its prime minister was elected and so on. We worked.

Aurela Kadriu: Did you experience any kind of persecution because of your engagement?

Adem Mikullovci: I was persecuted because I came from Slovenia to visit my son and my wife. Mainly my son. And on my way back, the police caught me and sent me to prison. I stayed in prison in Valeva for a few days, eight days and seven nights and then they released me, because as I told you in the beginning, the further they are from Kosovo, the less Serbs care about Kosovo. The judge and prosecutor were surprised by the demand of Serbs from Kosovo to arrest me because of my words in the parliament when in fact a member of the parliament is entitled to immunity.

They even told me, when they released me they told me, “We have kept you for too long.” We agreed for them to call me again, they called twice but I never went again, everything went to hell and I didn’t go again.

Aurela Kadriu: Why didn’t you return to the theater?

Adem Mikullovci: I didn’t want to, I started working, I started making movies for television with video cassettes, TV dramas and shows, I made five-six TV shows. I didn’t want to return to the theater anymore. I have to be honest, as long as Zarić was a director, as long as Serbs were there, he called me, they invited me to become part of the theater when I was released but I said, “I will never come as long as you are the director…” And I didn’t want to go. I didn’t want to go. After the war I got old and…

Aurela Kadriu: In what projects did you work at that time? What TV shows, which ones? Maybe it would be good…

Adem Mikullovci: My TV shows are…I don’t know. Maybe Mahmutovitët dhe Rexhepovitët [The Mahmuti and the Rexhepi families] is the most famous one, then there is Mahalla jonë [Our Neighborhood], then Katundarë e Sheherli [Peasants and City People], then Burri me tri gra [The Man With Three Wives]. Then Zogjtë e Luftës [The War Birds] which was broadcasted in RTK, twenty episodes for war orphans. Then Rrëfimi nga gjyqi [Confessions From Court] which was broadcasted in RTV 21. These were my TV shows. I also played in many television movies, over twenty television movies. I have three-four TV dramas that were broadcasted in RTK, after the war. This is how I worked.

Aurela Kadriu: What kind of satire, what kind of comedy was it, especially the one used at Mahmutovitët dhe Rexhepovitët? That one is very famous, it is…

Adem Mikullovci: Yes…

Aurela Kadriu: It is maybe part of the collective memory.

Adem Mikullovci: Yes, you are right. That’s true!

Aurela Kadriu: What kind of satire was that?

Adem Mikullovci: Through people’s comedy we tried to tackle, how to say, the negative sides of our nation. For example, not to have good relations with the neighbor, neglecting each other, this kind of conflicts, marriages. I was focused in those elements that are still present in our society. You can see that by looking closely in the parliament, the antagonism between political parties, I am so surprised and sometimes I say, “When I see you now, I realize that I wasn’t that far, I wasn’t that wrong at Mahmutovitët dhe Rexhepovitët.” (Smiles). Because we really are like that.

Aurela Kadriu: In which year was Mahmutovitët dhe Rexhepovitët shot?

Adem Mikullovci: Ah dear girl, years and numbers, once numbers are mentioned, I am useless. I swear to God I don’t know the year.

Aurela Kadriu: Where were you during the war?

Adem Mikullovci: I fled to Montenegro. I was in Ulcinj. There was a Montenegrin living one floor below my apartment, he was an UDB[13] commander, and I told him two-three months in advance before things got worse, I told him, “Dragan, no matter what happens, either you save me and I save you.” And the Montenegrin gave me his word that we would do it like that, if things got worse for Serbs and Montenegrins I would help him. And I don’t know where he is, whether he still lives or not, he was an UDB commander, but he drove my wife, my son and I through Mitrovica and Rashkë to Montenegro, Ulcinj.

We exchanged phone numbers but he never called again. Because he said, “I won’t return either, I will desert the army, the police…” I don’t know whether he was killed or what happened to him I tried to give him two thousand Deutsche Marks of that time, back then we were using that currency, but he didn’t accept it, there was no way he would accept it. The same person helped the late Masar Stavileci to flee, the father of Blerand Stavileci. And when the police took Blerand, because he was older than my son…I don’t know how old Blerand was, he was around twelve-thirteen-fifteen…The Montenegrin helped Masar’s son, he took him home from the police station.

Aurela Kadriu: How was making movies before the war? How were the movies made before the war, how was it?

Adem Mikullovci: I don’t know what to say. Before the war, all the movies were made by companies from Belgrade and Zagreb. They are more skillful than we are, they work better and maybe even pay better, to be honest. We are slowly learning, there are new movie makers of your age, I see them making their way and I am happy, for example that Agim Sopi’s movie Agnus Dei received one hundred awards from different festivals. They are slowly getting on their feet but we are still far, we are still far.

Three men from Switzerland who had watched my TV shows and movies came two years ago to me and said, “Baca Adem, we have decided to give you the money to make a movie about Adem Jashari.” I had such a hard time explaining those men that we are still not capable of making a movie of Adem Jashari. We have no capacities. We cannot make such a movie even if we come together with Albania. It is extremely expensive, the police costume, the technical part from Serbia, the scenography…The role is the smallest issue, because we can find somebody to play it.

And as one of them told me, there is a legend, I don’t know whether this is true or not, but he told me that Albanians had spoken to Mel Gibson and he was very interested to come here and make that movie. Only Hollywood can make such a movie, we can’t. I am speaking about making a good movie, because as for a bad one…

Aurela Kadriu: Have you ever worked in directing?

Adem Mikullovci: I was the director of everything I spoke about until now, the TV shows that I mentioned. These are all directed by me. The TV dramas as well. I also directed seven or eight theater shows in the theater. Directing was my second love (smiles). Because I told you that when I was in the Academy, I took interpretation classes before noon and directing after noon. And I always had the dilemma whether I made a mistake for choosing interpretation instead of directing.

Aurela Kadriu: Earlier you mentioned the opening of the television, were you anyway related to it? Did you ever work there or something?

We collaborated, we collaborated with the television after it was opened in Albanian and the first TV shows started. It was an event at that time, the TV show directed by Muharrem Qena Qesh e Ngjesh, it was a comedy played once a week, everybody was excitedly waiting for Saturday to watch Qesh e Ngjesh. Then after Qesh e Ngjesh, there came the Pa pengesa [Without Obstacles] TV show. Then there were other TV dramas, I can say that I believe I played in the first TV drama produced in Pristina, it was named Skerco and was directed by Muharrem Qena. Skerco was a comedy drama that was first titled Miu në xhep [Mouse in the Pocket] but then they changed its name into Skerco.

We worked a lot at that time. I belong to the generation of the actors of that time, together with Dibran, Çun and others, Kumri Hoxha, Drita Krasniqi and some others, it happened that we had rehearsals before noon, afternoon, and then we had a play in the evening, and spent the whole night shooting in the television. And then there were the radio shows Humoreska, Ora Gazmore, Radio Drama, we couldn’t manage to do everything. When Kosovafilm started engaging us, that’s when we were absolutely lost.

Aurela Kadriu: What did you do at Kosovafilm?

Adem Mikullovci: Kosova Film made some very good movies. Kosovafilm made Era dhe Lisi [The Wind And The Tree], for example, and many other movies. Proka, no, Proka, is new, it was made later. But we made movies with Kosovafilm.

Aurela Kadriu: How did you find home when you returned after the war…

Adem Mikullovci: It was alright when I returned after the war. There is an interesting story here as well, because I wanted to take a book, I had left it near the television and I had left two thousand Deutsche Marks on it and when they came to kick us out, I asked them to take the book, he said, “Take your wife, your son and get on the car right now.” We left to Montenegro, I said, “Can I take the book?” “No, leave the book.” He didn’t let me take the book and we went by the sea, we went to Montenegro. One of my neighbors who was living one floor below me broke into my apartment, he wanted to occupy it so when I returned, the door was broken but we went inside and I went to the book, it was still near the television and the two thousand Deutsche Marks were still there, he didn’t know how to find them, he didn’t know how to catch them. When something is yours, nothing can take it from you.

Aurela Kadriu: What did you continue doing after the war? How did you restart? How did you find yourself?

Adem Mikullovci: Like that, we started making movies for video cassettes. I started making comedy, I made more comedy movies, I also played music, I worked for the others because I didn’t have my own money until one day somebody knocked on my door, and this is an interesting story. Somebody knocked on my door dum, dum, dum and I was eating breakfast with my wife, our son was little at that time so he was at school. I opened the door, there was a boy in front of it. I said, “Why are you knocking? What do you want?” He said, “I want food.” I said, “What?” He said, “Food!” We were used to beggars coming to beg for money or clothes, but he only asked for food.

I told my wife, “Lume, please give something to eat to this boy.” She made him a sandwich with cheese and salami and I don’t know what and gave it to him. I continued having breakfast and my wife told me, “Come, come to the window.” When I went to the window, I saw him with another boy sitting near the containers eating the food, they seemed so hungry. They were miserable. I went and talked to them. They told me that their father was killed during the war, their mother got married and now they were living in a basement with their grandmother. “Eh,” I said, “Adem Mikullovci is making comedy and look the drama that is going on out there.” I am sorry, only something else…In fact, their father was in prison, he wasn’t killed but he was in prison and their mother had left them and gotten married so they had remained with their grandmother. Who is taking care of political prisoners? And for three days I wrote the script for the movie Një pallto për babain tim në burg [A Coat For My Father in Prison]. I wrote it for three days. Shani Pallaska was in the main role but I had troubles finding the boy. I don’t know if you have watched it or not.

Aurela Kadriu: Yes, I have heard of it.

Adem Mikullovci: Eh, the movie was very famous. They were all bringing boys that were raised with chocolate [had good lives], they bleed no matter where you touch them but I wanted a good one. The one who played the role was someone who stayed in front of the theater all the time, “Baca Adem, do you want cigarettes, baca Adem, do you want cigarettes?” Until my eyes were opened and I said, “Wait, who are you? I took him to the apartment, I asked him to read the text, I saw that he could do it. Then I worked with him for one week in a row until we started shooting. This is the story with him.

This how, these things happen, they happen, a spark should exist, an inspiration to engage people. I was in the bus, I was going from Mitrovica to Peja. At the Peja Bath a young man comes on, pale, skinny, physically looking like me. He sits next to me. I look at him sideways, old pants, patched shoes, wrinkled shirt, like that. I say, “What do you do for work young man?” He said, “I, baca Adem,” because he recognized me, “I’m a teacher, I teach. I have a class in Boga.” In Rugova, in the mountains. I said, “You travel every day?” He said, “No, not every day, but every other day, every three days, I have to go because my mother is here. My parents aren’t well, I have to take care of them, so I travel.” And he said, “I was released from prison a month ago. I was in prison for seven years.” “Oh, God!” I said.

Just like for the other boy I wrote the drama for four-five days, the film, the script for the film “Mësuesi” [The Teacher]. And I wrote it based on what he told me. That he got out of prison, started working at the school in Boga, but in reality they released him from prison to die in his house because they killed him in prison. He actually was a dead man, murdered. They destroyed his lungs, his heart, everything, and he dies and he dies there.

You know, I want to say, there’s always a spark, that stimulates a person to start something, like an inspiration and then, then it goes. When I was filming the TV show “Mahalla jonë” [Our Neighbourhood], while editing something, the editor says to me, “Do you agree with my thesis? My theory. He told me about a theme, a content, and jokingly he asked if I agreed with his thesis. I look at him, awesome. I made three episodes of the TV show “Mahalla jonë” with this sentence, with my thesis.

Because I connected the script, Xhevat Xhena and Zenel Tufa, Xhevat would tell Zenel, “Get married, your wife is dead.” In that time, while they’re talking about marriage, a reporter comes and asks them about contagious diseases. She lectures them and in the end she asks, “Do you agree with my theory?” They say, “Of course, we agree, how can we not? If your aunt wants to, we agree.” Then I squeezed this sentence for three episodes, a single sentence, “Do you agree with my theory?” It’s about inspiration. I think whoever does art should find it somewhere, to hold on to something, an inspiration, a painting can inspire you, a discussion, a story, a look from a person.

Aurela Kadriu: How did you decide to get involved in the Assembly?

Adem Mikullovci: Eh, my involvement in the assembly is, to tell you the truth I’ve always had my apartment at the Alliance [Alliance for the Future of Kosovo], and I would go play chess with Ramush [Haradinaj][14] everyday, I would drink coffee and hang out with him. But I told Ramush to his face that I supported Vetëvendosje, a Vetëvendosje supporter. He would tell me, “What are you doing with those troublemakers from Vranjevc? Have you gone crazy, come to my party, I’ll make you a Member of the Parliament .” I didn’t want to go.

But when I moved to Bërnicë, I had some sort of acquaintance, a shallow friendship with Albin Kurti[15]. Albin came to me insisting, two-three times, for me to be a Member of the Parliament , to run for Member of the Parliament . “Nobody will vote for me…” I used to tell him. “Yes, yes.” “Nobody will give me their vote.” It turned out that I got 13000 or I don’t know how many, I got many [votes], I accepted and I was more active in Vetëvendosje.

Aurela Kadriu: What do you engage in today? What is your involvement in the Assembly?

Adem Mikullovci: Look, it’s interesting, my discussions, my requests, were never shown in the media. I’m involved with some cases that are more vital for Kosova. For example I dealt with, why didn’t we sue Serbia until now? For all those murders, for all those missing people, all this economic destruction, a hundred and twenty thousand houses. And we still haven’t sued Serbia. While we should file at least ten, fifty lawsuits. And we still haven’t filed not even one lawsuit against Serbia. Only Reçak should file a lawsuit, Krusha e Madhe a lawsuit, Prekaz a lawsuit. I presented this.

Nowadays, I’ve dealt a little more with the Pension Fund and the savings of citizens in Jugo Bank, for Serbia to give them back, because they stole the Pension Fund of Kosovo. And so on, I’m trying where I see it’s best, to contribute in commissions, different commitments.

We have a session tomorrow, I have two difficult questions to ask them. Because I want to propose, to propose in the assembly since Serbia is constantly referring to us, in letters, in acts, wherever it is written, Kosova and Metohija, I’m going to propose that we refer to Serbia from now and on as Serbia, Vojvodina, and Sanjak. Vojvodina is the Autonomous Province of Serbia, Sanjak is an annex of Serbia with the majority of non-Serbian population… So we change their name, too. They refer to us as Kosova and Metohija, we refer to them as Serbia, Vojvodina, and Sanjak.

I don’t think the assembly will accept it because it will be scandalous. Imagine if Vlora Çitaku says Serbia, Vojvodina, and Sanjak in the United States. The Serbian delegation would leave the meeting immediately. The discussions that we are not having with Serbia, if they all stick to this, and they always say Serbia, Vojvodina ,and Sanjak in writing and discussions, I guarantee that they will stop the discussions. This is how I am, I’m still spoiled. I tease.

Aurela Kadriu: Are you still involved with film and theatre?

Adem Mikullovci: No. I’ve given up.

Aurela Kadriu: For how long?

Adem Mikullovci: For how long, since I’ve become a Member of the Parliament . I also quit my show in the theatre, I can’t play anymore. I don’t have the strength, one hour and fifteen minutes playing the role of myself alone… I noticed that I was playing more of my last shows sitting down rather than on my feet or moving. You can’t force it and I quit. Two-three days earlier a guy called me, “Baca[16] Adem, a short film…” I said, “It’s not going to happen, I’m done.” Good, bad, I did what I did, that’s it.

Aurela Kadriu: If you don’t have anything to add, we can end it here. Thank you very much.

Adem Mikullovci: Well, I don’t know how this conversation will turn out to be honestly. If the viewers will like it, or if they will not like my memories, my emotions. I want to summarize it a little but, we said a little and a lot remains unsaid. Like any other person, all of us have a lot, a lot to explain about our lives. But most importantly, remember, this life is full of slaps, full of slaps and very few kisses.

[1] Faruk Begolli (1944-2007) was a prominent Kosovo Albanian actor and director in former Yugoslavia. He attended high school in Pristina and graduated from the Academy of Film in Belgrade. Begolli acted in more than 60 films.

[2]Enver Petrovci (1954-) is a Kosovar actor, writer, and director. He went to high school in Prishtina and completed acting school in Belgrade. He played as Hamlet, Macbeth, Julius Cesar, and other famous Shakespearean characters. He is one of the founders of the Dodona Theatre and the Acting School in Prishtina.

[3] Velimir “Bata” Živojinović (1933–2016) was a Serbian actor and politician. He acted in more than 340 films and TV series and is regarded one of the best actors in former Yugoslavia.

[4] Bac, literally uncle, is an endearing and respectful Albanian term for an older person.

[5] Rilindja, the first newspaper in Albanian language in Yugoslavia, initially printed in 1945 as a weekly newspaper.

[6] Çun Lajçi, or Çun Alia Lajçi, (1946) is an Albanian musician, author, theater and film actor, drama teacher, lahuta player, and activist. He is famous for reciting The Highland Lute. Lajci has played over 200 roles and has been in 30 movies.

[7] In Albanian customary law, besa is the word of honor, faith, trust, protection, truce, etc. It is a key instrument for regulating individual and collective behavior at times of conflict, and is connected to the sacredness of hospitality, or the unconditioned extension of protection to guests.

[8] Turk. terzi, tailor.

[9] Refers to the The Brotherhood and Unity monument which was inaugurated in 1961, while Josip Broz Tito was the leader of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia. The monument has three sky-high pillars, which join together at the peak, each pillar symbolising a member of the brotherhood of Yugoslavia within Kosovo – Albanians, Serbs, and Montenegrins.

[10] The Constitution of Kaçanik 1990, was written to give Albanians freedom, fairness and wellbeing within Yugoslavia and stipulated that the people were the ones who select their wellbeing and futures. The head of the meeting on 7 September 1990 was Iljaz Ramajli.

[11] Alb. UÇK – Ushtria Çlirimtare e Kosoves, Kosovo Liberation Army.

[12] By 1991, after Slobodan Milošević’s legislation making Serbian the official language of Kosovo and the removal of all Albanians from public service, Albanians were excluded from schools as well. The reaction of Albanians was to create a parallel system of education hosted mostly by private homes.

[13] Serb. UDB, Uprava državne bezbednosti, State Security Administration.

[14] Ramush Haradinaj (1968), leader of the KLA from the region of Dukagjin, founder of the political party AAK (Aleanca për Ardhmërinë e Kosovës) and was elected twice as Prime Minister. In 2005 he was indicted at the ICTY for war crimes and crimes against humanity and acquitted of all charges. He was retried and again acquitted in 2010.

[15] Albin Kurti (1975) leading activist and former leader of Vetëvendosje!, is Member of the Assembly of Kosovo. In 1997, he was the leader of the student protests against school segregation and the closing of the Albanian language schools.

[16] Bac, literally uncle, is an endearing and respectful Albanian term for an older person.