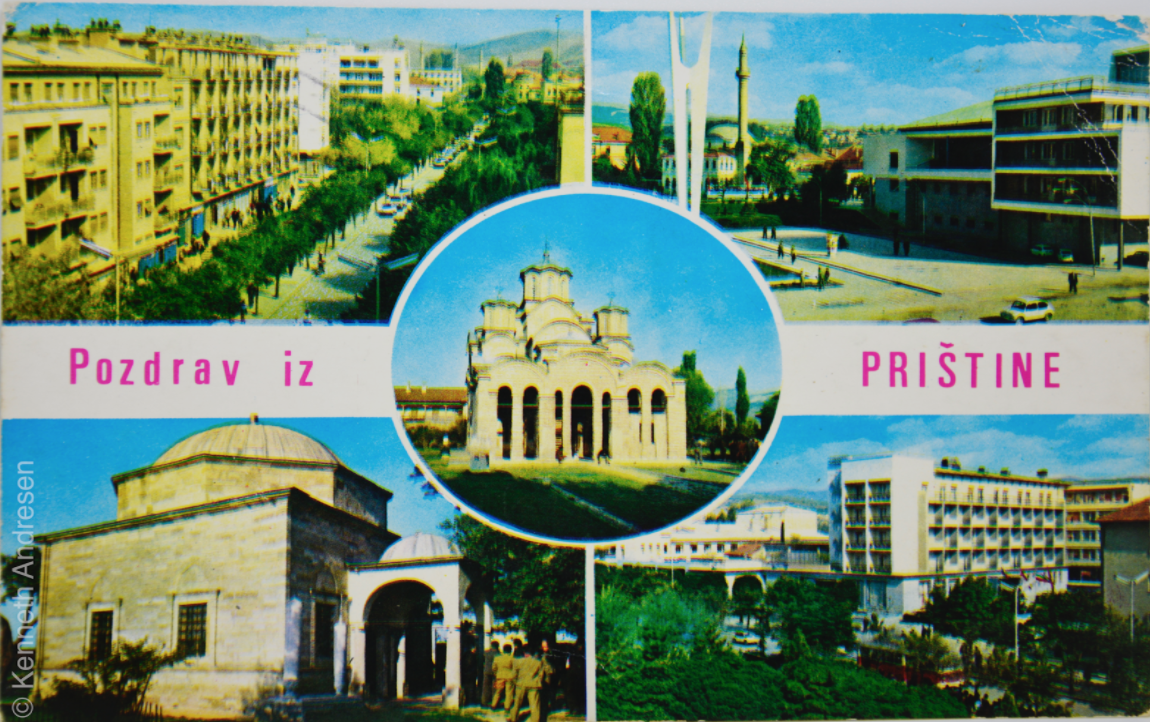

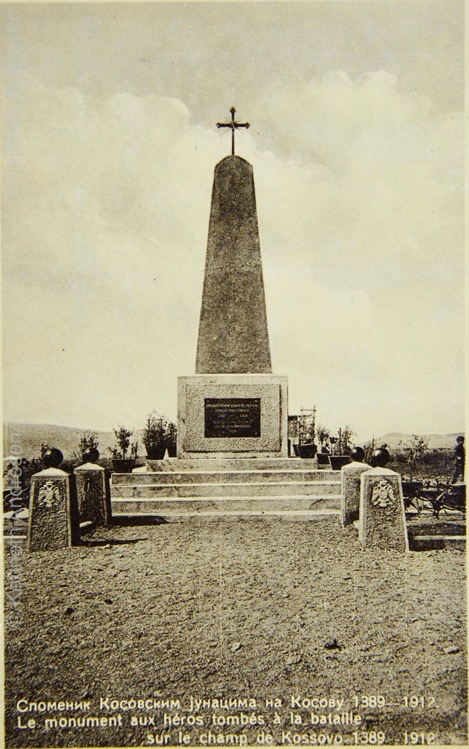

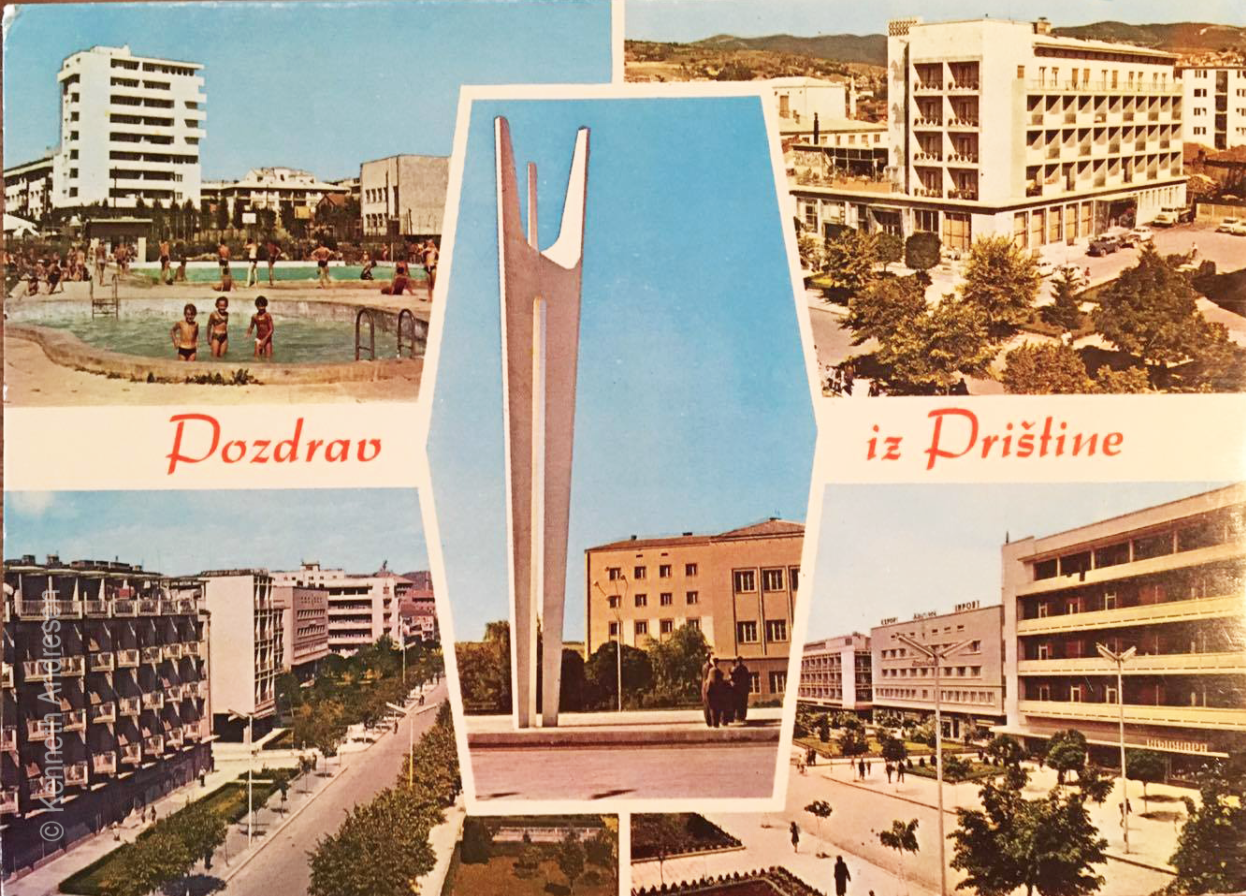

Return to Sender: One Hundred Years of Postcards from Kosovo

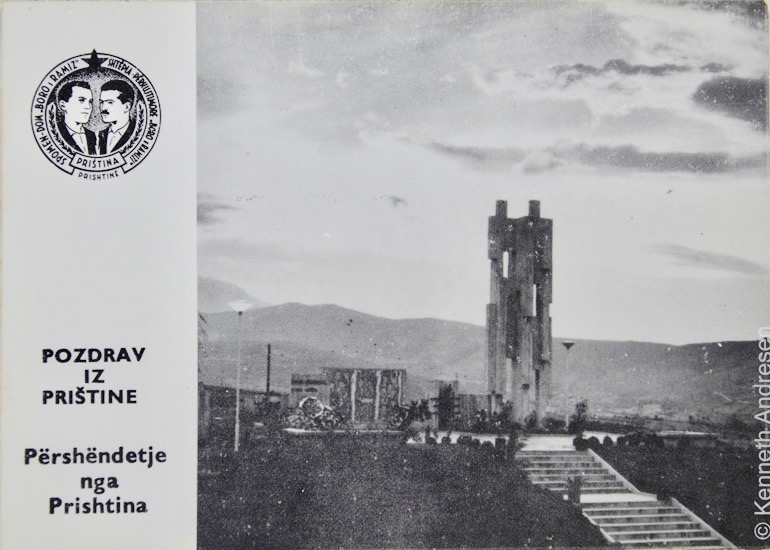

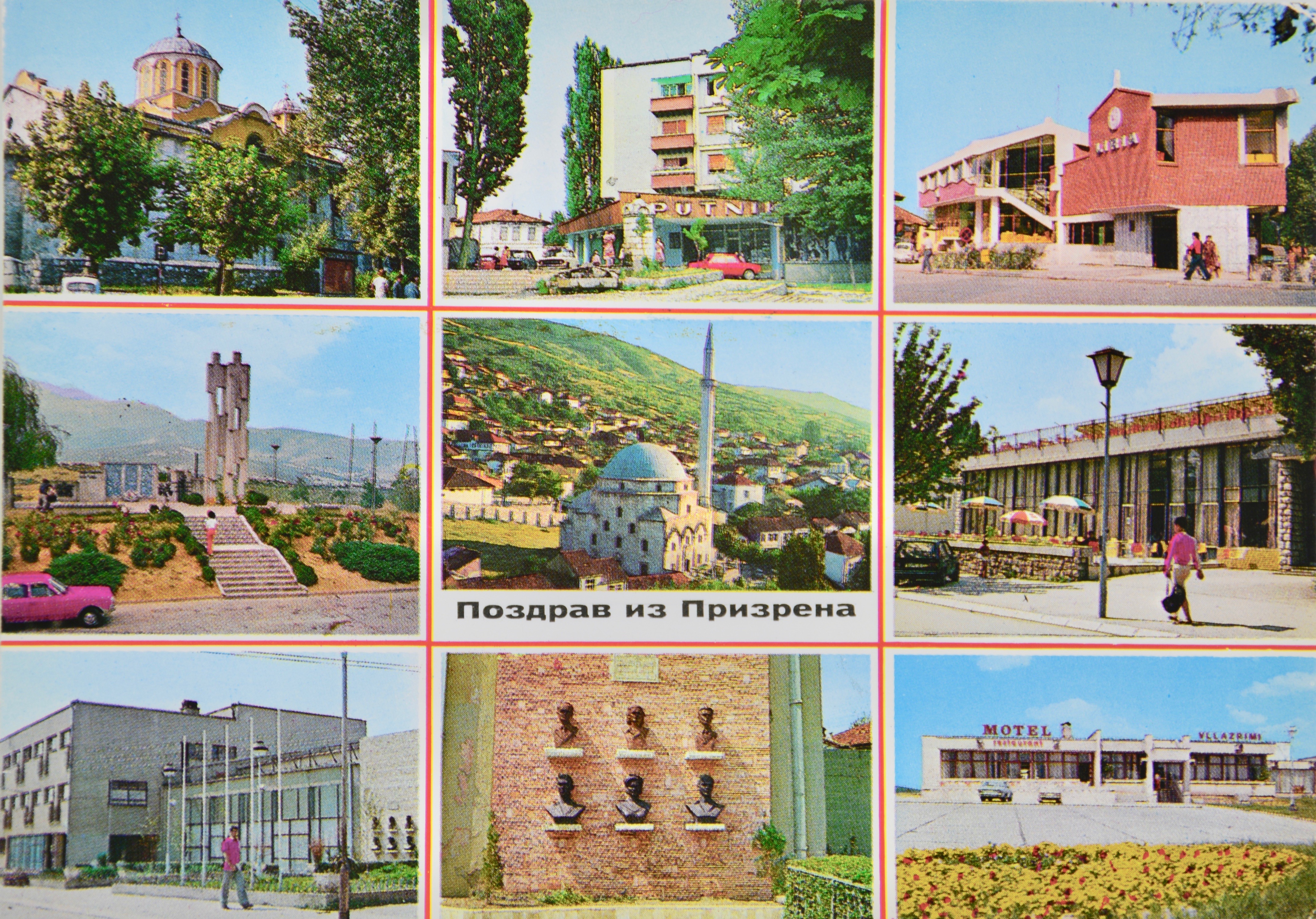

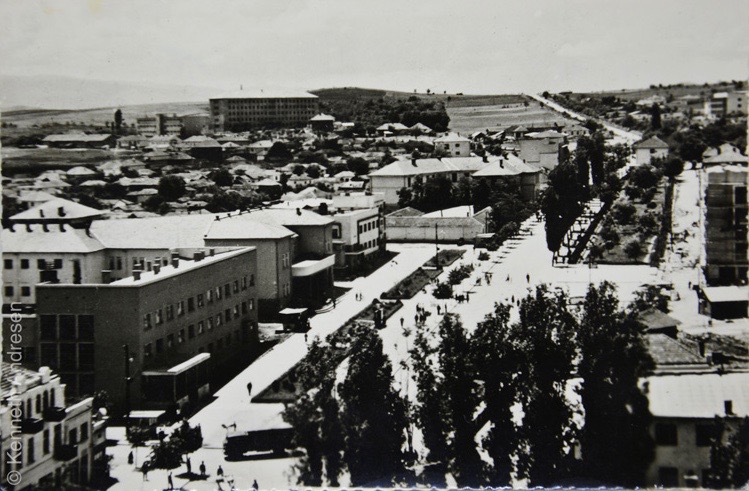

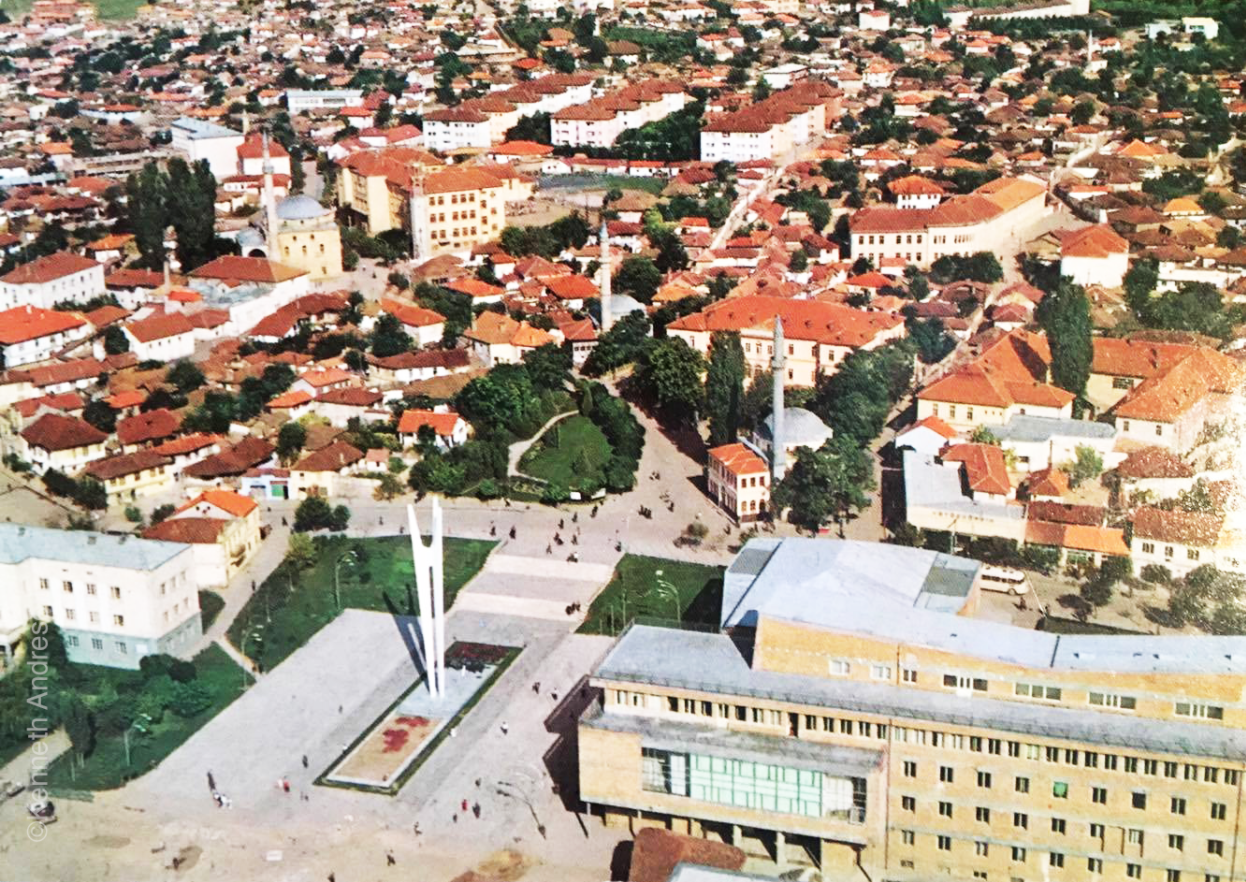

What do we remember of the victory against Nazi-Fascism in Europe, seventy-five years ago? Images of monuments to the Second World War provide us with traces of memory: of Yugoslavia’s promise of brotherhood and unity among different nations, of Kosovo’s dream to become modern and prosperous, and of rising artists’ promotion of a modernist aesthetic.

Built in the 1960s, those monuments were since destroyed or rendered invisible by neglect. Thanks to the collectors who preserved and exchanged them, postcards restitute them to public view after a half century. As we look at the monuments, we cannot avoid thinking of their absence, which is not absence of memory as much as the counter-memory of contestation and alienation.