They were stranded, you know, they were under the siege of Serbian forces and could not secure food or basic medicine, for which they were in dire need, because they were surrounded by police forces. The protest was organized on March 16, 1998. We planned to start the march in Dragodan, at the America Embassy [Office]. There were a great number of women and girls, who, each of them held in their hands a loaf of bread and medicine, hoping to get to the families stranded in Prekaz. So, at the very beginning of the gathering there were various provocations by different people. But we did not stop the march. […] Near the Agricultural High School, throughout that part of the march we had people following us with cars that had Serbian plates. They provoked us, shouted at us, they tried to scare us or… but we did not stop, we continued marching, we did not shout back at them because we knew very well why we were going there. In one moment, I don’t remember it myself very well, it was a matter of seconds, and one of them drove the car into the crowd of women protesters. From that point on I don’t know what happened, I lost consciousness, I was one of the women who were hit by the car and I don’t know. I don’t remember what happened afterwards.

March of 1998 was a month of many protests. The women’s informal network organized eight out of eighteen peaceful protests held in that month. The protests were in response to the violence exercised in Drenica, Kosovo by Milosević regime. Through protests, women activists called out to international community to intervene and put an end to violence. This series of interviews map out the history of women’s activism in the public sphere, shed light on women’s political positioning, and forms of resistance in 1998.

The interviews were produced in partnership with ForumZFD, University Program for Gender Studies and Research and Oral History Initiative.

Lindita Cena

LawyerFlorina Duli

Executive Director of IKSThe first protest was with white sheets of paper, the second with bread for mothers and children of Drenica. The bread protest was organized at a time when Drenica was entirely isolated from the rest of Kosovo. […] The goal of the walk was not simply to send bread there, so it was more about the effect it had on the international media, so we stopped and turned there. […] I personally bought the bread and I think each… there was enough bread and bakeries gave away bread, but there were also people who bought it when they left the house, since we knew we would… You cannot imagine the level of solidarity at that time, it’s indescribable. Back then we didn’t think about the material side of our political engagement at any moment, there was always a way. […] There were also many protests which were simply symbolic, so they were an expression of the revolt that people needed to express, it was necessary for people to find an outlet for all that revolt that was built in them over the years.

Gjylshen Doko Berisha

Director of the Gjilan MuseumMrs. Lemane was my mother’s first cousin, the daughter of her maternal uncle. She completed the High Pedagogical School in Tirana and I think I inherited from her the desire to study Albanian Language and Literature. The way she taught us from fifth to the eighth grade was very unique. She would take the record player and play us poetry from well-known [national] poets, such as Naim [Frashëri], Andon Zako Çajupi, and others. So, we listened to recitals and music. She was like that, very good-hearted but also very harsh and that intimidated us. She was my aunt. When she came by our house to pay us a visit, I would hide in the other room. My mother would take me out by force. I would say to her, ‘No, because she… she’s my teacher, I can’t show my face.’ So when my mother took me by force in the room, she would praise me in front of her. But what happened recently, quite recently, because she passed away four-five years ago, I went to her and asked her, ‘Aunt Leman, I always liked them, where did you get the poetry recordings?’ Today, no teacher would take the effort to do that. She said, ‘I recorded them myself. It was my voice.’ She had a very ringing voice, very melodic, but as a child I never thought it was hers, I thought it was just a recording.

Ajnishahe Azemi

Professor of Philosophy and SociologyWhile talking to my students, together we saw it fit and we decided to open our school [Xhevdet Doda], but it was characteristic how we would open the school on both sides, on both wings {shows with her fingers} of the school there were two tanks. While discussing it we were deciding that if we open the school door, the main entrance, they would see us, stop us and we wouldn’t achieve anything with that, and then the violence, repression against us. And I said, ‘You know what? We are allowed to open the school elsewhere,’ because I knew it well, I worked for a long time. I said, ‘Since this is an old building and it has some window bars, but it’s possible that those bars, maybe you can do it together and we can remove those bars and get in through…’ it was the window in the basement, of the bathrooms {describes with her hand} of the basement. And we went there with those 17 students and we decided to open it. […] They did not stop us, nor did others come to stop us from opening it. And we stayed in that school. Of course, they came to school later asking, ‘How did you open it?’ and so on, but not to get us out of there. Maybe it was, how do I say it, a political maneuver so they could say in front of the world, ‘We are letting them, but they don’t want to. There’s this school that works in their school premisses, because we are letting them, we’re not stopping them.’

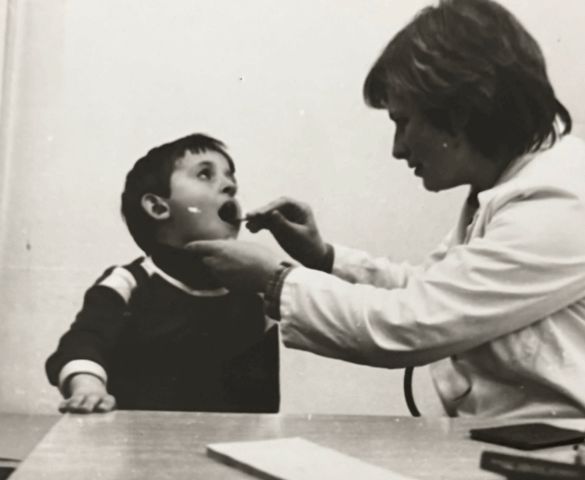

Flora Brovina

Poet/DoctorMy little sister was small when we visited our father in Peja. In Peja’s prison, which was filled with Albanian prisoners. Why do I know this? As a child, well I was quite little myself, I wasn’t going to school yet. I know because in front of the prison all the families that came to visit the prisoners gathered and had a bag in their hand {makes a move to describe the bag}.

[…] But these miseries that childhood carries will follow us throughout life because childhood [experiences] leave a trace. Luckily it did not fill me with hatred and I like that oblivion did not take over. I remember them because I never took them as personal, but I believe I share them with all the people who waited to visit theirs in prison. I share them with all the people who have been excommunicated, politically persecuted families, excommunicated by the society, a time when your neighbors did not pay you a visit because they were afraid.

Albertina Ajeti-Binaku

Architect…we had no tendency to give it a political connotation. It was more about giving it a humanitarian connotation, because families for days, with weeks have been under the siege. There was no free movement, you know to be able to go out and get supply, food and other things. And this was it. You know, we as mothers, as women who sympathize with mothers at that time in Drenica, who had no food for their children. […] And I remember that we were like, you know we were in a row and on the side we had police forces. Until we reached that point, then we were not allowed to go further. [Women] They wanted to negotiate, but they were not ready. So with an authoritative statement they ordered us, ‘You have to go back, otherwise we cannot risk, because then anything can happen to you and we cannot protect you…’