Part One

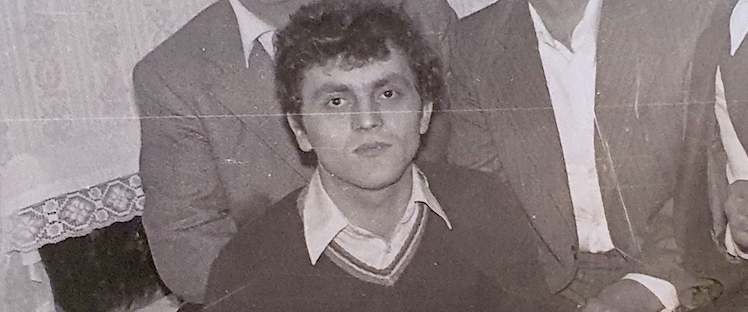

Anita Susuri: Mr. Sherafedin, if you could tell us your name, last name, date and place of birth, anything about your family.

Sherafedin Berisha: My name is Sherafedin Berisha, I was born on November 9, 1954, in Pristina, into a poor working-class family. My father worked at the city flower shop and provided for five members of our family with his income…

Anita Susuri: Where was it, the flower shop, where was it in Pristina?

Sherafedin Berisha: The flower shop was on the street that takes you, on the way to Isa Mustafa’s roundabout, as they call it, there, before arriving at the gas station, across from it. At the Croatian Embassy, near the Croatian Embassy, there was the city’s flower shop. They planted seedlings too and they maintained the whole city. The trees which were planted at the Economics School were planted by that generation and almost all the city trees, they removed a large number of them, that generation planted them after the war. Sometime around the ‘50s.

Anita Susuri: You told me about a family history about how they came to Pristina.

Sherafedin Berisha: Yes, the first from my family who came here was Hajrullah Fetah Berisha. He came here between 1820-1825, I don’t know exactly, he came with only his mother. I don’t know the reason why it was only him and his mother because I didn’t manage to find out. He came to the city, he lived here. He got married when he grew up, Hajrullah got married to a girl from the city, she was from the Toperlaku family. Actually, during the time, after my grandfather grew up, they called him Fejzë Toperlaku because he was raised by his [maternal] uncles. He came here at four years old, the first one, Hajrullah, but my grandfather Fejzullah also lost his father at the age of six. So, he was raised by his uncles.

Hajrullah had four children, yes, he had Fetah, Fehmi, Fejzullah, and Fetije. The youngest one was a girl. He, one of them, Fetah, was a soldier in the Turkish [Ottoman] army back when this area was under the Turkish [Ottoman] Empire. He died but we don’t know where, my grandfather didn’t know when his brother died either. His other brother died in Pristina of an illness. Right when the time to get married had come, he got engaged and everything, [that’s when] he died. My grandfather lived… my father’s [paternal] aunt too, my grandfather’s sister, she lived until ‘72, she died in 1972. While my grandfather died in 1977.

My grandfather also had five children, three sons and two daughters. They were Nazmi, Ismajl, Fetah, Xhevrije and Fahrije. Out of all of them, only Xhevrije is now alive at the age of 86, all the others have died. My father then got married and he also had five children. I am the oldest, and then there’s my brother Xheladin, Fehmi, Sheriban and Nerxhivan, and Bastri. The last one, Bastri, is the youngest. We are all alive…

Anita Susuri: You told me another story which sounded interesting, how to put it, your older [paternal] uncle, who was in the army there and he ran away from the army…

Sherafedin Berisha: It was my grandfather.

Anita Susuri: It was your grandfather?

Sherafedin Berisha: He was a soldier eight times, they mobilized him eight times. Because he was a parentless child, an orphan, and they put the army clothes on him, let’s send someone who has no one to care about them. The big shots of the city registered him instead of sending their sons, without his knowledge. He was in many Arabian cities, he even learned Arabic really well and he also knew Turkish. He would tell me that, one time, he tried to run away from the Turkish army and he walked around, he wandered around, and he didn’t know where to go.

He told me one time, he said, “I was tired,” he said, “I went inside a home, one stable, and I saw a cow manger and I slept there. But,” he said, “I had a dream that my sister brought me food, I was hungry, and I got up and left crying. On my way, I saw an Arabian woman and she asked me, ‘Why are you crying?’ I told her and said, ‘I am crying because this happened and I had a dream where my sister brought me food,’ she brought out,” he said, “two pitas,” because back then they held those pitas on top of their heads, “and she gave me two pitas.”

“I ate them,” he said, “I sated my hunger a little. On my way,” he said, “I saw some women who had taken their small child in front of the door and they said, ‘Will you sing something to this child because he won’t stay put, he’s got the evil eye on him,’” those superstitions. He said, “I said some dua,” he said, “that I knew. They gave me,” he said, “some money and with that money,” he said, “I survived two days. I had enough to eat. I wandered around, I wandered, and I went back to the barracks where I was a soldier again because I didn’t know where to go.”

Anita Susuri: He didn’t know where to go.

Sherafedin Berisha: And he told me, “We got a disease too,” I think it was typhus, he said, “there were doctors who came from England and cured us.” It’s interesting, he sang a song of the War of Çanakkale, it’s in Turkey. But he sang it in two versions, Albanian and Serbian, I mean Turkish, excuse me. I would ask him, “Why?” He would say, “I learned it as a soldier there, I learned it in Turkish but then I also heard it in Albanian and I sang it in Albanian.”

Anita Susuri: Did he translate it or did it already exist [in Albanian]?

Sherafedin Berisha: I don’t know, I don’t know. It exists because people sing about the War of Çanakkale. And I was here in the gymnasium, a gymnasium student, it’s on the main street and then there is an alley to go to my house. I would hear him singing it from the end of the street. It’s interesting because he died in his own room, he never ate his bread without toasting it. I would hear him chewing when I was in the yard, the [crusty] bread would go krrup, krrup {onomatopoeia}. He was very strong until the last year of his life.

Anita Susuri: How long did he live?

Sherafedin Berisha: According to the records, 105 years. But according to some historical events that he would talk about, we would calculate around 115. Now I don’t know which one… but even 105… I was small and I would tell him because I’d call him old man, I would say, “You live for as long as you want, I will live two years longer than you” (laughs). And I joke around now too, I say that I made a contract with my grandfather [to live for] 117 years but it’s not sealed, it’s only between me and my grandfather (laughs). Now, I don’t know.

Anita Susuri: I am interested to know, how did he come back?

Sherafedin Berisha: He came back because those Arab contingents went back. When he came back, he went… and he married a little late. He had a friend and he was my grandmother’s brother. She was much younger. Actually, I would often joke around because I called her old mother, I would ask her, “How do you know grandfather?” She would say, “Always like this, with a beard.” Because he was a little older when they got married, and they had many children, the ones who lived, because three of them died. One of them was a little challenged, he didn’t know what fear or hurt were. My grandmother would tell me, she said, “He would come,” she said, “the dogs had bitten him but he wouldn’t even wash it off.” But then she raised the children, my father, my two uncles, and her two daughters.

Anita Susuri: What did he do after…

Sherafedin Berisha: He was a shepherd because he was raised poor, he was raised without a father, he looked after the sheep of a man here in Pristina.

Anita Susuri: Do you remember any stories about what Pristina was like back then? The rreth? Kosovo in general? I mean, based on his stories.

Sherafedin Berisha: Yes, he would tell me about some places that were in the field, for example, the part going towards Podujeva, Kodra e Trimave [neighborhood] as they call it, that was all fields. And then, the road that takes you… and to, yes, there was a store there at Kodra e Trimave, I don’t remember, there was a cemetery. They removed everything and they sold land, they built houses there later. The part of the road to Kolovica, about 300-400 meters beyond the Technical School, it was a hill, it was all a graveyard. The city cemetery. And then, there was, in Pristina there were a lot of çeshme,which were built with soil pipes, they were supplied with water.

There was a çeshme which they called Çeshmja e Hynilerëve. There was the old folks home, there is still an old house built with adobe. Actually when I told a worker at the Kosovo Archives, I said, “Look at the House of Hyniler,” he said, “What do you mean [the house] of Hyniler?” I said, “They called them Hyniler,” the old-time residents. And there was a çeshme until recently. And then, where my house is, it’s Haxi Zeka street, and then Enver Berisha street which takes you to the new Medrese, and we called that area Kajnak. There was a çeshme there, the water was sparkly. But when the river Pishtevka was covered, that çeshme stopped working.

Anita Susuri: The water was sparkly?

Sherafedin Berisha: Yes, yes. But not as much as, for example, bottled sparkly water, but it was naturally sparkly. And then there was the mill, at Llapi street. Oftentimes, when it rained a lot, the water came down from the villages of Gollak there, there were cases, the haystacks were brought down by the flood as they were placed because of the heavy rain. And there was a bridge near the mosque, it would often flood and the water would go above its normal levels. What else can I say? But, I don’t know if I told you, I think here, behind the theater, Vellusha was covered, the river. Because it was covered [there at first], and then it was covered up to Taukbahçe [neighborhood] there. As a child I would go under it, behind the theater I would go to the river and I would go where the Shota Assembly offices are, at the Pristina Stadium, that’s where we went. But there wasn’t much…

Anita Susuri: Did you swim, or?

Sherafedin Berisha: No, there wasn’t a lot of water. It was below the knee, there wasn’t much water. But it became less and less every day. It’s interesting, maybe I’m jumping from topic to topic, the Prishtevka river used to flow from the village of Gollak. My [maternal] uncles live in a village nearby, Makoc. When I went to visit them I had to walk on the bridge, it only fit one person, there was a plank because I couldn’t walk in the river because the level of water was above the knee. Now there isn’t even one drop of water, the water disappeared. These are some of the things which I remember in a kind of telegraphic way, how to put it.

Anita Susuri: You said that your father worked in a…

Sherafedin Berisha: Flower shop.

Anita Susuri: What about your mother? Was she a homemaker?

Sherafedin Berisha: A homemaker, a homemaker. My father finished school where the gymnasium is, back then it was an elementary school. He was the best student in class, it wasn’t just something that he said, but there was a Bankosdirector who said so, and there was Izjadin Osmani, a children’s doctor, they were classmates. And that bank director told me, “We were nothing compared to your father.” But they were wealthy families, they went on and studied in medrese in Skopje. One of them continued… because there were two medrese in Skopje. One of them was called Kral Aleksandër, the other one Isa Beg.

Anita Susuri: Maybe one of them was for muslims, one for…

Sherafedin Berisha: It was mixed, but one of them was public, Kral Aleksandër, and Isa Beg I am sure was owned by some man who funded it. And he couldn’t go there anymore because he had to pay.

Anita Susuri: And he finished the gymnasium…

Sherafedin Berisha: He finished it here, he was the best student, with the best grades.

Anita Susuri: Sami Frashëri.

Sherafedin Berisha: Sami Frashëri, but back then it was like an elementary school, it lasted four years or what was it. And it’s interesting because my father told me when he defended his graduation thesis, he said, “The people of the commission told me, ‘If you agree to marry a Serbian girl, we will educate you.’” My father said, “No.” He grabbed the hoe and worked the garden. We also had a garden and we sold products in the market.

Anita Susuri: You didn’t tell me about what kind of family your mother came from?

Sherafedin Berisha: My mother’s family was based in Makoc village, their last name is Krasniqi. Her father, my grandfather was named Martir, he later went on to become an imam. She had four other sisters and two brothers. My mother was a calm person, very kind-hearted. My father was a little strict because he was fair, he never accepted injustice and spoke his mind no matter who it was to. He didn’t allow, for example, to be misused although that flower shop was state-owned, he never even had one flower seed in his pocket. He was very just.

Actually sometimes I would tell him, “Too much. You did too much!” In one case, the organization offered him some land where the Pejton neighborhood is. Without charge, plus they would give him credit to build a house. And he didn’t take it. I asked, “Why didn’t you accept it?” He said, “I didn’t accept it because we would be indebted to the people who the state confiscated it from.” “But you didn’t confiscate it, you weren’t the cause of the confiscation.” “No,” he said, “I didn’t want to.” He didn’t accept it.

Anita Susuri: I wanted to ask you about the customs, for example, in your house, or your mother, what kind of rules did you have at home? How were you organized as a family?

Sherafedin Berisha: My mother was the oldest bride because our family lived in a collective. I was the oldest child among my uncles’ [children] and so on. I helped my mother a lot because I had to, with everything, to prepare the food, to send it to the workers in the field and in the garden. And I helped her, I baked the bread, I cleaned the yard. I always helped my mother, now I help my wife too. I have the right to, I’m saying, because I helped my mother too (laughs). My mother was a villager but after some time she adapted to the customs of the city. The only thing is that she never learned to speak Turkish. My grandmother knew it, and my mother didn’t. She never learned Serbian nor Turkish.

I had Serbian neighbors, but I didn’t learn Serbian. In the fifth grade of elementary school, because we had, I had six [school] subjects in Serbo-Croatian language. There were no Albanian teachers, there was that subject Basics of Technical Education, the professor was about to fail me because he was Serbian. But with the whole class insisting, he gave me a two and I passed. During the summer, out of spite, I took a, there was a sports newspaper called Tempo, that’s what it was called. At first I didn’t understand, I only understood shoot, goal, out, nothing else. I understood those terms because I watched football. I read and I read, I read the whole summer. When I started the next school year, everyone was surprised. The professor would say, “You knew it, you didn’t want to speak it but you knew the Serbian language.” And then I spoke it fluently. I learned it from the newspaper.

Anita Susuri: Do you remember how your house looked at the time you were a child, your neighborhood?

Sherafedin Berisha: The houses were, most of them with wattle and daub, the ones with mud. Our house was, we had a, it was a bit more sophisticated, I mean, there was also a basement because the yard was kind of steep and the main street was kinda higher. There, on the first floor there were four rooms, we had some kind of hayat, as they call it, now it’s a terrace, and below we had a place where we kept our animals. The other area of the yard we had the sheepfold because we had sheep too.

And then, when the change happened here in the city, Nazmi Mustafa was the mayor, he did it, he contributed the most in developing the infrastructure of Pristina. The Agim Ramadani Street and the UÇK Street were built by him. The Pirshtevka and Vellusha rivers were covered by him. He was a hard worker. The only mayor who has always had a municipality deficit, never a surplus, because he has completely spent the funds. He worked a lot for Pristina. Of course, it was the system of that time, but he cared about this place. That’s how I see it now. Anyway, I jumped to another topic.

Anita Susuri: [We were talking about] Pristina, when you were a child.

Sherafedin Berisha: Yes.

Anita Susuri: Your neighborhood, for example.

Sherafedin Berisha: It was a street cobbled in stone, not in cubes, but stone. Actually, my father would tell me during the time of former Yugoslavia, “We each had,” he said, “the obligation to go out in front of the house and clean the street because they punished you if we didn’t.” The neighbors, most of them were Albanian, there were two or three Serbian families.

Anita Susuri: Were there neighborly friendships, for example, visiting each other…

Sherafedin Berisha: We all knew each other because there were very few newcomers, but we knew everyone, we had comings and goings. In fact, I don’t know, there’s an interesting fact because that street, Haxhi Zeka, they refer to it as “near Mursel Shumari’s house,” but before it was called Gjymrykhane. Gjymrykhane…

Anita Susuri: Some kind of han?

Sherafedin Berisha: Excuse me?

Anita Susuri: Some kind of han?

Sherafedin Berisha: No, it was some kind of customs point. When the people came from the village, they had to pay a fee to the customs for the products they brought to sell at the market. There was one customs point there, one was where the cathedral is now. On both sides of the city, they couldn’t come into the city and sell products [without paying that fee]. That’s what it was like at the market until recently, I don’t know if they pay anything now, you had to pay for using the market to sell your products. And back then, in order to get into the city there were those two points where people were checked.

Anita Susuri: So, that means the location where the cathedral is was the entry point to the city?

Sherafedin Berisha: Yes, before that school which was there was built, Xhevdet Doda. First there was the police station there, then later on the gymnasium was built.

Anita Susuri: How do you remember the infrastructural development of Pristina? So, you were grown when that began.

Sherafedin Berisha: Yes, Lakrishte [neighborhood] for example, that land was a garden where different citizens planted stuff, there were no buildings. Those buildings began being built in the ‘70s maybe. But they were built following a plan, not like today where you can give a cup of coffee to your neighbor from your balcony. Construction was regulated. For example, the soliter buildings are the last buildings where Pristina extended to as a city before arriving at the hospital, there were no other buildings in that area. And then later on the dormitories were built and the more aggressive, so to say, development began. They overlooked some stuff back then too.

Anita Susuri: How did you personally experience that change in the city? From a town, how to put it, it turned into a big city.

Sherafedin Berisha: I was surprised by some stuff. Actually, when the retail store was opened, the new one, it seemed very interesting to me that it had an escalator, there were different kinds of products there separated by floor, there was furniture, clothes, and food items. The food items were in the basement, it was something new. Maybe… because later on the TVs arrived too, in black and white back then.

When we saw some other countries it seemed interesting to us. Even when I went abroad in the ‘90s, some things seemed interesting to us because we didn’t have them. Every vehicle, these [popular] brands, they were only commercial vehicles here, there were no other ones here back then. Here,there was only Ramiz Sadiku and Eurgens which maintained buildings and there was nothing else here. And after there were some construction companies like the one from Peja and some others, when they built the south area of the city.

Anita Susuri: What elementary school did you attend?

Sherafedin Berisha: The school, back then, now it’s Pjetër Bogdani, back then it was Miladin Popović, the school’s name. It’s the road when you pass beyond the Technical School a bit, you turn to the left. That’s where I finished elementary school, and then I enrolled in gymnasium.

Anita Susuri: Were there Albanians too?

Sherafedin Berisha: There were both Serbs and Albanians.

Anita Susuri: Parallel…

Sherafedin Berisha: Yes, and then there were Roma people too. There were two Roma girls and a boy in my class.

Anita Susuri: They learned Albanian?

Sherafedin Berisha: Yes, they learned Albanian. And sometimes we would argue with the Serbs, and they would mix with us. There was one girl, her name was Xhevrije, if I’m not mistaken, she was physically big, she would fight them (laughs). I was the smallest in class physically. But then I quickly grew bigger during gymnasium.

Anita Susuri: I am interested to know if back then there were trips or visits which were organized by the school?

Sherafedin Berisha: Yes, we went on trips, for example, to Taukbahçe, and then we went to the theater. Here, the street across from the gymnasium, do you know where the Ethnographic Museum is? There was a zoo near the museum there, there were animals…

Anita Susuri: The House of Emincik?

Sherafedin Berisha: Yes, the House of Emincik.

Anita Susuri: Do you have an idea what it was like there? Did you go?

Sherafedin Berisha: You mean the museum or the zoo?

Anita Susuri: Yes, the zoo?

Sherafedin Berisha: The zoo, there were several animals, not a lot though. I think there were lions, wolves, foxes… and I don’t know if there were any pets there. See, I don’t remember because I’ve started to forget because it was a long time ago, around ‘65 I think, I don’t know what year to say.

Anita Susuri: I think I also heard a story that a wolf escaped from there and attacked someone?

Sherafedin Berisha: I don’t remember, no, I don’t know about that.

Anita Susuri: I think I heard about it.

Sherafedin Berisha: It’s possible, it’s possible. Because it wasn’t that secure there although there were bars but everything is possible. My father really wanted me to enroll in medical school. I would say, “No, because I couldn’t cut a person to perform surgery.” “Well, alright,” he said, “go become a dentist.” “No, I don’t think I want to be a dentist.” And I sent my documents to apply for the gymnasium.

Anita Susuri: At Ivo Lola Ribar.

Sherafedin Berisha: Ivo Lola Ribar, that’s what it was back then. And I took the entry exam, I passed it and then my father came from work and asked, “So,” he said, “what did you do? Were you accepted?” I said, “No, I failed just by a bit.” He asked, “Why are you lying?” He said, “You were second in the list” (laughs). He was a big fan. Every time I told him [to buy me books], he went out to different publishing [houses], novels and stuff, at that time books would come in from Albania, he never told me no. He gave me the last of his money so I could buy books.

Actually there was a Xha Limani [Alb.: Uncle Limani] near the theater, where they sold books. He would wave at me, “Come because there are new books” (laughs). Now his niece or daughter has one here, Xha Limani, there is a bookstore here. And it became… there were occasions when my father gave me money to buy shoes, and he waved at me that there were new books, I bought books and left the shoes.

Anita Susuri: Were there other bookstores?

Sherafedin Berisha: Yes, there were, there were.

Anita Susuri: Did you drop by them?

Sherafedin Berisha: There weren’t many… it’s interesting because Xha Limani had many books, publications from Tirana that came there for the first time. There were other publications [at the other bookstores] but I am not aware that there were books available from Tirana because there was Rilindja, and I don’t know, I don’t remember. There was, where it is now, there was a bookstore Skënderbeu there and that coffee bar where Union is, there was a hotel there, a restaurant. And then there was a jewelry store, one of them sold electricity products, lamps and stuff, across from them there were those film ads near and then there were the bookstores too.

Anita Susuri: You mentioned the films and said that you visited those cinemas with the school too…

Sherafedin Berisha: The cinema, the theater, yes.

Anita Susuri: Which ones, I mean, there was Kino Rinia back then, I think?

Sherafedin Berisha: Yes, Kino Rinia. It was named in Serbian, they called it Omladina…

Anita Susuri: Also [Kino] Armata…

Sherafedin Berisha: Where Armata is now…

Anita Susuri: Yes, it’s still there.

Sherafedin Berisha: At the same place, at the same place.

Anita Susuri: At the Zahir Pajaziti [Square].

Sherafedin Berisha: And there is that… for example, where the old shopping center, behind it, behind the Zahir Pajaziti statue, that’s where the church’s well was. There was the catholic church at [Hotel] Grand. There was a mosque where the theater is…

Anita Susuri: Llokaç.

Sherafedin Berisha: The Mosque of Llokaç, yes.

Anita Susuri: I wanted to ask you, at the cinemas, what kind of movies were there?

Sherafedin Berisha: There were various movies. There were regular movies, of course, of the system back then with partisans and the ones against Germans. There were Hollywood movies too, the ones with warships, with sword fights and stuff. There was, Anijet e Gjata [Alb.: The Long Ships], in Serbian translated as Dugi Brodovi. There were various movies. Then there were also Indian movies where people went to cry because they were sad (laughs). There were also some kind of horror movies. I went once and watched a movie three times, I was scared the same three times, I jumped from my seat.

Anita Susuri: Which movie was it, do you remember?

Sherafedin Berisha: There was a mummy in Egypt. He hits the wall and it falls down and makes a big noise. I jumped from my seat three times. I went there intentionally, just to see if I could [go without being scared] because I knew that scene was going to happen. It’s interesting, I reacted instinctively.

Anita Susuri: Do you have a memory from the other cinemas and the cultural life?

Sherafedin Berisha: I don’t know what to tell you. We visited the theater often, every show. Actually my class was very active in that. Even when we went to the movies, we went organized, only our class, for example. We agreed in that way so that us, the boys, would see the girls to their homes, we always saw them home. Whoever lived in a certain area… I had four [girl] classmates who lived in that area.

One of them was my neighbor, actually that girl’s father told me, “Even if I had a hundred daughters, with this kind of student, I would send them [to school] with no fear.” We took care of them like they were family. They didn’t dare to speak to another guy although they were of age back then in gymnasium, maybe they had a crush, but without asking for our permission they didn’t dare to talk to them.

Anita Susuri: They were like your sisters.

Sherafedin Berisha: Totally.

Anita Susuri: You mentioned something else as well that I have heard about the families who lived here in Pristina, they had a tradition to go for picnics in Taukbahçe, Gërmia…

Sherafedin Berisha: They also went to Sultan Murat’s Tomb there. On 1 May at Gërmia, always. Even the buses that were there at the time didn’t dare to make you pay for a ticket, nor the taxis or someone who worked privately didn’t dare to charge for sending you to Gërmia. There was music there, there were different bands. They would grill meat, make fliaand stuff. Those were organized there at Sultan Murat’s Tomb, for Saint George’s day as well, various picnics.

Anita Susuri: Was it, for example, for Saint Geroge’s day, was there a special custom, or just a picnic?

Sherafedin Berisha: Yes, for Saint George’s day as well…

Anita Susuri: There was some kind of [ritual], bathing in flowers.

Sherafedin Berisha: Those were at home, they didn’t do them there. Before breakfast they washed them, they put flowers in that water container, they put nettle and willows. They said, “The one who is asleep in the morning, will be asleep the entire year,” that was some kind of superstition. There were these customs, but they slowly disappeared.