Solitary confinement is a specific type of punishment. Confinement causes great trauma. Confinement causes great memory loss. A person could forget things which are unimaginable in a normal life. […] There were times, at specific periods there were no reading materials, no newspapers, no magazines, no books, nothing. Sometimes they would leave books. But mainly not, mainly not. And it was confinement within yourself. Then you would have to, I witnessed people in prison making a lot of noises because of solitary confinement, people trying to run away. It became very normal to me, I couldn’t imagine being in a place where I was not alone. I got used to solitary confinement and that seemed normal to me. An abnormal state in my psyche became normal.

I would think to myself, how will I be around others? Will I be able to adapt to having people around? 13 months. It was very difficult, the days wouldn’t pass by, they were very long. I was able to know where I was only based on the conversations they had with me or channeled towards me and I would realize then where I was. I had a lot to say, I still have a lot left to say (smiles).

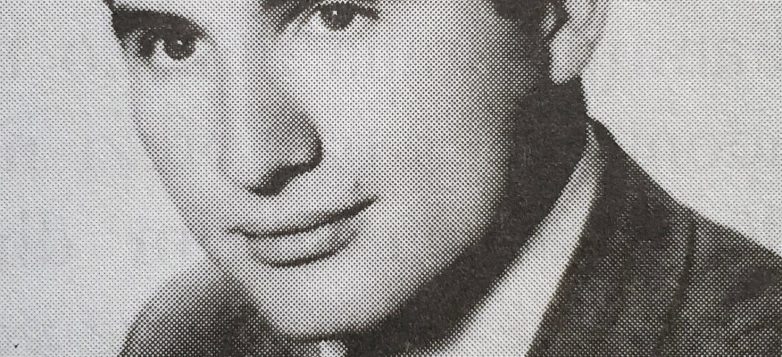

Meriman Braha was born in 1946 in Prizren. He graduated from the High Pedagogical School in 1972 in Pristina. He began working as a teacher in Kamenica and later on in Gjilan from 1970. He was politically imprisoned in 1983 and was sentenced to seven years. In 1990, he founded the League of Albanian Educators of Kosovo, who worked towards an independent education system. Whereas, after the end of the war in Kosovo in 1999, Mr. Braha worked in the Department of Non-Resident Affairs within the Ministry of Culture and later as deputy director of the Museum of Kosovo. He retired in 2011. Today, he lives with his family in Pristina.