Part One

Anita Susuri: What kind of memories do you have from childhood?

Memedali Gradina: First, I’ll introduce myself, I am Memedali Gradina, resident of Janjevo. I have lived in Janjevo since I was little, since I was six years old, until 11 years old. Then, I went to France with my family. I came back to Kosovo in ‘68, so in Janjevo. Janjevo, as I said, used to be Little Paris, that’s what we used to call it. Janjevo was known for its sausage.

They would come from different places of Kosovo and outside of Kosovo just for that sausage. That’s how Janjevo was known, from that sausage that was made here, Croats made it, of course. Back then, Janjevo had 7,500 citizens, in total, 7,500 citizens in total, Albanians, Croats, Roma, Bosnians, Turks.

There were no Serbs in Janjevo, there aren’t any even to this day. Janjevo, as I remember it, as I said, Little Paris, I remember when I went out as a seven-year-old child, in the center of Janjevo, Croats would buy groceries and I would carry their shopping bags, that’s how I would earn money for a day. So, that’s how powerful Janjevo was back then, those years, so from ‘75 or something like that, Janjevo…

Anita Susuri: Do you remember the city?

Memedali Gradina: This city hasn’t changed at all, it just got ruined, it got ruined… You might have walked around Janjevo, you’ve seen how many houses are demolished, because Croats left. Not after the war, they left before the war. Well, then war made it even worse, but before war, there were eight or nine cafés in Janjevo.

I remember when I used to go out to earn money, I would go into cafés, during the summer, there were no free places to sit. There were no free chairs. But a little… then it started to get blocked, I don’t even want to mention his name, because he left a scar in our hearts. When he [Šešelj] came to Janjevo, then the Croats started leaving, and since then Janjevo started to fade out.

Anita Susuri: Šešelj, right?

Memedali Gradina: Yes, Šešelj, then Janjevo started to fade out.

Anita Susuri: Let’s go back to when you were little, what did your family do? What did your father do?

Memedali Gradina: My father worked for the Croats, there were no state jobs, actually, there was a time when there used to be a factory, Metalac Factory, but to work there you had to know someone. Just like today, nothing has changed. So back then my father used to work for the Croats, with those machines that they used to produce kids’ toys and plastic mostly.

My mother worked in a butcher shop, she would make the sausages of Janjevo that I mentioned. That’s how they used to support us, because we were two brothers and three sisters. Back then we were little, but we were seven family members, my grandparents and uncles, we all lived in the same house. The house is down there. So, 27 people lived in two rooms. But slowly the time came… My father went to France by himself first.

We started school here. I went to school, so did my sister, the others were too young. But life was much better than now. Whatever we earned, what we ate was more delicious than now. For example, because now people don’t really have the willpower to live anymore. Back then, as children, eleven, twelve years old, kids, ten years old, we didn’t care about anything except having a little money and going to school and learning. Now if you ask youngsters, they don’t have the willpower to live or work. Back then, one person would work, 25 people would be able to eat from that salary. While now, even if 25 people work, not even ten people can eat from that.

Anita Susuri: You mentioned that your father worked in a workshop for Croats?

Memedali Gradina: Yes, in a workshop.

Anita Susuri: Can you tell us, for example, what were those workshops like? Which Croat homes had those workshops? Who worked there? Did they work by themselves, or did they get workers?

Memedali Gradina: A minority of Croats did not have machines to produce, but the majority had them. Most of the houses had them, and, of course, they had employees from Roma houses, people who worked for them. And there were three or four houses, people who worked at Metalac. But the majority of Roma people worked for them.

Look, we benefited a lot from our relationship with Croats, because we… Even today, there are two families here, I don’t know how many Roma houses work for them. I myself worked for them, but I left the job. However, before, before the majority of Croat houses had machines, they had workshops, but workshops were in their houses, at home. For example, part of the house was a workshop, and there they slept and lived. Like that, they managed to give a salary to the worker, they also worked and produced.

Then at one point, at one point, when my father started to build this house, then he was loaned a lot of money from his boss, the owner, how to put it, he took a loan to start building this house where we are at the moment. Then we had to start working for him, the children, the mother, all of us. Then he brought, now in this room where we are at the moment, it became a workshop.

We had two machines here, small ones with which we worked. However, the elderly worked with machines, the younger ones put pieces of them together. We made these hair accessories, those, I don’t know the names, you are young, I don’t think you have seen them, they were like eights, they had a stick with which you locked your hair behind.

We made those, we made those dolls for kids, toys, clackers, stuff like that… Stuff like that. We would split the workload, then we put those together, clackers. Here at our house, we have put them together, we made them. We put them together here and sent them in boxes to that owner there, that’s how we earned a bit and paid off the loan. Of course, my father had to go into debt to start building the house.

Anita Susuri: How old were you back then?

Memedali Gradina: What?

Anita Susuri: How old were you when you worked there?

Memedali Gradina: I was seven years old. I was seven years old, but however, my [paternal] uncles are really close, how do I say, they help each other… and back then, however, we were together, we lived in the same house. That house is down there, now no one is there. So they helped, my uncles, my cousins, we worked a little, we were like ten workers who worked and earned money. We earned enough money.

Anita Susuri: Did you work only with plastic, or with metal also?

Memedali Gradina: We also worked with metal, we used to make hair accessories, then we would turn them into an eight. We worked with metal also, but mostly with plastic. Mostly with plastic.

Anita Susuri: You said that your mother worked in a butcher shop…

Memedali Gradina: Yes, butcher shop.

Anita Susuri: You told us that Janjevo was known for its meat, sausage. Do you remember those butcher shops? Where were those? Who were the owners?

Memedali Gradina: Croats, the one who owned that shop was also Croatian. He also sold the meat and sausages that he would roast in the center, he had a barbecue grill and all of that. His workshop was down there. I know because I used to go there when I got hungry, to tell you the truth, I would go where my mother worked. I used to look at her while she would dry the sausages, before they even dry, she would say… she would give me some to eat.

Of course, back then there was more poverty, but it was sweet poverty, while now it’s a pretty boring poverty. Here in Janjevo, at this moment, I’ll get back to it. To this day, let’s leave… At this moment, there are like three or four Roma families that have a good life.

Now look, good life, what does a good life mean? A good life, for me, my wife works, I don’t work, but she does alhamdulillah [praise be to God]! There are people who don’t even have this much. My mother gets 90 euros from her retirement, she has that, my wife is a teacher, she is a teacher here in Janjevo, alhamdulillah [praise be to God], it’s good.

Anita Susuri: What was it like for the Roma community back then, when you were a kid, what was life like then?

Memedali Gradina: Look, Janjevo back then, as I mentioned, I have to mention again, was Little Paris. No one cared what or how you are. To this day, we live here as brothers, no matter if they’re Roma, Turks, or Albanians. To this day we are… I remember as a kid we didn’t care what was happening outside of Janjevo.

We lived in Janjevo, “Brotherhood and Unity,” that’s the saying. And when someone would build something, so to say, if they built a bathroom, we would all go and help. While now, if you buy something, no one helps you carry the bag without pay.

Anita Susuri: You… I wanted to ask you about the Roma community, you told me… back then, even the owners talked in Roma language with their employees, so Croats also spoke Roma. Is this true? Do you remember?

Memedali Gradina: Look, the Croats who have houses in Roma neighborhoods spoke the language better than we did. And the owners, of course, learned the language, but the Croats aren’t the only ones who speak the Roma language. If you go out in the center right now, there are a lot of Albanians who speak the Roma language. That’s why I said, before and after war, we’re still with the “Brotherhood and Unity” idea. We didn’t have any problems here, not even during the war, we didn’t have any problems.

Anita Susuri: What about the city, do you remember the cafés there, Bash Çarshia, and another one next to Bash Çarshia?

Memedali Gradina: Yes.

Anita Susuri: Do you remember? Was it there even then?

Memedali Gradina: Yes, Bash Çarshia is quiet… I remember when I would come on holiday, that when Bash Çarshia was opened, it was where the bakery is now. I don’t know if you were at the center? Where the bakery is now, that’s where the café was, so when I was little, seven or eight years, there used to be a Croat who made coffee there. Then there was another café a little further… You don’t know how many cafés Janjevo used to have. Many cafés, for the young people, too.

Anita Susuri: Do you remember in which year Bash Çarshia opened?

Memedali Gradina: Bash Çarshia, I think in the beginning of ‘80, around that year.

Anita Susuri: Was the owner Croatian or Albanian?

Memedali Gradina: No, the owner was Croatian. He also had a butcher shop, he had the butcher shop and that café. He would make Janjevo sausages. He opened that café. Then after the war, it was bought by some Turks. And near that, where the mosque is, in case you have seen the yard of the mosque, there used to be a café there too, but then the mosque bought that land.

Anita Susuri: What about a café near there, an old one, 1928, do you remember that? They say that it used to be a café then a shop…

Memedali Gradina: In front of Bash Çarshia?

Anita Susuri: Yes.

Memedali Gradina: In front of Bash Çarshia, there used to be a state-run café, a state-run café. They used to have singers and stuff, I remember that surely, I remember because 55 years ago…

Anita Susuri: Were you ever there? What was the atmosphere like?

Memedali Gradina: The atmosphere was, how do I put it? That will never return. That atmosphere will not return here. That café was always full. There was music, they had singers. The young and old went there, even the middle-aged. Whoever could get in, whoever had money, of course. You cannot enter a café without money to pay for drinks. There were no divisions, no one cared if you were Croat, Roma or an Albanian. No, no, no. Regardless, we ate and drank there together. All together. We had no issues among one another. But I don’t think that time will come back. Life was really tasty, life was sweet.

Anita Susuri: You went to the Vladimir Nazor School, right?

Memedali Gradina: Yes, it was called Vladimir Nazor back then.

Anita Susuri: Do you have any memories from that time?

Memedali Gradina: I used to go to school there. The teachers were mostly Serbians. Of course, the majority were Serbian, because there were also Croatians. It used to be a Croatian-Serbian school, Albanians went there also, but we were separated. The school… back then, actually it’s a shame if I complained, because to this day, I don’t have any problems with the school, when we used to go out during the breaks, we would all hang out together. For example, what we would get… back then we didn’t have enough money to buy snacks in the market like now. But we would take, for example, we would take sandwiches or something from home. Some would forget to take them, or they didn’t have enough, we would share. It wasn’t possible for some to eat and some not to eat. Like now, they go buy snacks for themselves, and they don’t even say, “Take some,” to those who can’t afford it. No, back then we all ate together.

Anita Susuri: Do you remember any more details about Janjevo before going to France?

Memedali Gradina: Well look, there are a lot of details. Back then, Janjevo people had three-four cars, to begin, for example, I was eight years old when I cut this finger, at the time, there were three or four cars in Janjevo, or not. People had a lot of wealth, but there were no cars. Janjevo was always a calm place, Janjevo never had problems.

Janjevo as Janjevo, if the Janjevo Croats stayed and did not leave, at the time, we called Janjevo a Little Paris, today, we would call it Big Paris. But Lipjan was always poor, it is like that to this day. Even during Serbian time, and even now it is like that.

Anita Susuri: Do you remember when the municipality building existed? The municipality building of Janjevo?

Memedali Gradina: Look, at that time, I had already moved to France. When they started, I had already moved to France. Then I wasn’t here at all for about four-five years because they wanted me to go into military service. I, to be honest, that’s why I fled. I didn’t come because of my military service. I noticed Janjevo had changed a lot after seven years or something when I came for holidays. Because Roma, the minorities would work, but they didn’t work in the market, selling things. But after they went, Romas started trading.

Anita Susuri: So at that time, before you went to France here… the library was near the Roma neighborhood, do you remember?

Memedali Gradina: Yes, yes. There used to be a cinema where the post office is now. Maybe you saw where the post office is? That area in front of the post office… now there’s nothing there, the library used to be there. There used to be a library there, I used to go to the library and get books to read. There used to be a library, those Roma you saw living there, they’re living there because of the time… the library was upstairs, they used to live downstairs, so they’re left there.

Anita Susuri: How did they live there? Did someone give them permission to do that?

Memedali Gradina: I think the state let them live there.

Anita Susuri: It’s a huge space there I think…

Memedali Gradina: That’s where the cinema used to be.

Anita Susuri: Did you ever go to that cinema?

Memedali Gradina: Yes, of course. We didn’t have TVs back then. I remember, now going back, my grandfather had bought an Ambassador Television in ‘72. That’s when we built this house. We used to put the TV on the window, we would sit in the yard and watch movies with people from the neighborhood. When I was very little, before we bought the TV, there were two or three TVs in our community. We had two or three TVs.

We used to go and watch movies, once a week they would bring them from Lipjan. They would have movies, of course, we had to pay to watch them. The cinema was like the ones in Pristina. In Pristina there still might be cinemas to this day, but they’re not as popular as back then (coughs), because now there are different programs on TV.

Anita Susuri: Do you remember what kind of movies you would watch? Do you have any memories? Did you go there with your friends?

Memedali Gradina: Yes, with my friends, with my friends, for example, I had the money to pay for three cinema tickets, whoever did not have, someone had half of the money, but not the rest. We gathered it between ourselves, we were ten or twelve friends, we gathered the money. Regardless if I had more or less money, we bought the tickets and got in. We watched a movie with cowboys or Indians, that’s what was available back then. And some movies from India, that’s what was in the repertoire back then. Then after a long time, sometime in ‘75, ‘76, around that time Turkish movies began, we called them Kara Murat and stuff, I remember that. We watched Turkish movies, karate, those from China and stuff like that.

Anita Susuri: That part where the cinema used to be, were there any celebrations held there, like weddings?

Memedali Gradina: Yes, yes, yes. When they stopped showing movies there, that hall was left empty. No chairs or anything. And then they, mostly Roma, would have weddings there because…

Anita Susuri: It was spacious.

Memedali Gradina: It was spacious and free. You could put chairs and tables there. I remember, it was very good at that time, they would have weddings there, and it was more beautiful than now, when they have them in restaurants. Because look, when my son got married ten years ago, but it wasn’t their fate to live together, we had the wedding in a restaurant. Believe me, it wasn’t as beautiful…

Anita Susuri: What were the weddings like?

Memedali Gradina: The wedding food was prepared at home. They didn’t order food in the restaurants. Two or three women would make food at home.

Anita Susuri: For example, when you were celebrating, did Croatian and Albanians come?

Memedali Gradina: Always. There were no weddings without Croatians, Albanians or Turks, no.

Anita Susuri: Was the Roma neighborhood always here? Or is there any other neighborhood in Janjevo where Roma families live?

Memedali Gradina: In Janjevo, there’s only one Roma family in the center. They bought that house after the war from a Croat, also there’s an Ashkali, well, he’s Roma too. The Ashkali is in the road uphill, he is there, but we were here in this part that you can see, we were always here.

Anita Susuri: Were the neighborhoods divided?

Memedali Gradina: Look, some were next to each other, so they were called the Roma neighborhood, the Turkish neighborhood on the other side…

Anita Susuri: On the other side of the river?

Memedali Gradina: Yes, on the other side of the river, the Turkish neighborhood was on the other side of the river. Then, most of the Croatians were in the center, the Albanians were uphill, like this, Albanians were also down there. There were always the Roma neighborhood, Turkish neighborhood, Latin neighborhood, Croatian neighborhood, next to each other.

Anita Susuri: What about you, did you have the same culture, for example, did Croatian or Turkish culture affect you, how did you get those traditions?

Memedali Gradina: Look, we got our traditions more from Croatians, because we worked more with them, and we were friendlier with them, that’s why. But what can we do, that’s how it used to be back then, even now, for example, most of them can’t speak Albanian.

Anita Susuri: Croatians?

Memedali Gradina: No, no, Roma. Most of the Roma community can’t speak Albanian. Why? Because they didn’t have as much contact with them [Albanians] as they did with Croatians. They would work for Croatians, they would befriend them, they would work and be their friends. For example, Croatians had two or three kids, they would be friends. As they would say, the money attracts (laughs). That’s… but we still lived together no matter what.

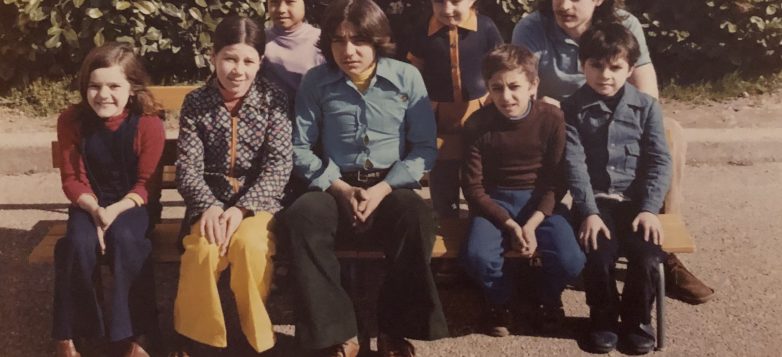

Croatians were more wealthy and stuff, but we lived together regardless. For example, when there were different celebrations, it’s impossible to not invite Albanians, Turks and Croatians, impossible. For example, there’s a video I can show you when I came back from France because my brother was getting married…

[The story continues in part two]