Part One

Anita Susuri: Mr. Dilaver, if you could introduce yourself, tell us anything about your family, your origins…

Dilaver Pepa: I am Dilaver Pepa, born in 1955 in Peja. I come from a middle [class] family, from the city, that works with crafts their entire life, as photographers. Otherwise, my father worked as a trader too when he was young, he went through all of Yugoslavia, former Yugoslavia, at the time… they visited many places with carpets, with… And my [paternal] uncle was a photographer… the first photographer, Riza Pepa, but sadly in 20… 20… in ‘43, ‘42, I don’t know exactly, he was killed. Now, we don’t know who killed him, whether he was killed by the partisans or the ballist, it’s still an enigma [mystery] that they couldn’t solve.

So, my childhood, like all people my age at the time, was school and games. We had our store, ever since ‘55 actually, when I was born and even earlier. I already started going to the store as a five-six year old, not to work, because I was small, but to send water, to help them with something, went to buy this, went to buy that. So, I started the craft a bit later on, I worked a lot when I was 15-16 years old. I mean, I was skilled enough that I was able to work. I finished elementary school in Peja, Miladin Popović [school]. The Gymnasium which was called 11 Maji back then, now it’s Bedri Pejani, in Peja. I started my studies in ‘74 at the Faculty of Law. I dropped out during the third year. The reasons were various.

Anita Susuri: I wanted to ask you about your father’s store. Where was it located and how do you remember it as a child… what did the store look like? What did it have inside? What kind of people visited it?

Dilaver Pepa: Yes. Our store was actually… I mentioned earlier around ‘50, ‘55, but I don’t remember that because I was born in ‘55. But we had our store… what I remember and if [you know] Peja… I don’t know how much you know it… now there is the goods house. That’s where our store was until ‘73. It was a store which connected to the long bazaar actually, in one line. The store was quite, I mean, for the time, well-equipped. It had reflectors, not flash reflectors like they have now, but light reflectors. There was a large camera, where people had their photo taken, for documents or for fun. Back then it was quite interesting to go and have pictures taken. People would prepare a week ahead, “We will go and take a set of pictures.” So, the store was simple… I mean, you know, not like many studios are today, but it was functional.

Back then there were few photographers. In Peja, for example, there were only two-three photographers. Foto Pepa, Foto Nazmia, and so on. So, all the time, after school, while I was in elementary school, I went straight to the store. My youth [childhood] was spent more in the store than in the streets, in the neighborhood where we played. So, this is some kind of…

Anita Susuri: You mentioned that your profession was handed down to you by your uncle, that he was the first to work…

Dilaver Pepa: Yes.

Anita Susuri: …with photography. Do you know anything more from… how he worked with photography? How did it come about that he started this profession?

Dilaver Pepa: {Shrugs} As much as they explained to me, I don’t know my uncle… we only know him through pictures. He was young, 17-18 years old… I don’t know if he was in Zagreb or where… they traveled back then, with trading and stuff, and he started the craft from… I don’t know now, you know, I am not sure who got him into photography. When he came to Peja, from there… at that time there were no photographers at all in Peja. Maybe there were but… we don’t know about it. So, he did photography. Back then he didn’t have a studio, but he worked at home. Back then the conditions were exceptionally hard. He had to photograph at home, to… to prepare a dark room. Back then he used the bathroom and covered it… and he had to work there and develop the films, develop the pictures, dry them and so on.

And after my uncle… he actually disappeared in ‘42-’43, then my father continued it. Since he was left with some cameras, some equipment, there were no photographers in Peja, and so he continued it. So, he started working [with photography] a lot, he left trading because he had a trading store, before learning the craft of photography. And he started with the craft of photography… slowly, slowly, my sisters began… I had three sisters. One of them… the older one didn’t work. Lirije Pepa did work, the second one along with Mersije Pepa. They are the ones who actually worked with photography their entire lives. My older brother, Skender, he also studied… they all studied but all of them… something happened and their studies were interrupted. After Skenda [Skender], me and another one of my brothers… we all worked with photography, actually, the entire family, aside from my mother and my older sister (laughs).

Anita Susuri: You also mentioned the trading store you had… I am interested to know with which places the trades happened, was it with Istanbul, or Europe, with Yugoslavia and these places… Croatia, Slovenia?

Dilaver Pepa: Back then… according to what they say, what my mother says and stuff… It was done with Istanbul, with Greece. Now former Macedonia, Skopje, back then it was in the Kosovo vilayet… in these areas. In Albania, in Shkodër, since Shkodër was closer to us as a city… they went there often. They traded with people from all around. When he opened the store, back then it was like a mini-market today, you know, it had everything. But I don’t remember that, only from what they tell me… I remember when we were photographers, when our house was near the goods house. We worked there… It was there until ‘74. In ‘74 we moved to… after the Municipality undertook the responsibility to build the Good House, they gave us a store in front of it and so we continued.

Anita Susuri: I am interested to know what it was like back then… I mean, when you were a child, how do you remember… the classes of people or what kind of… how to put it, people… you were like… maybe traders had a better economic standing. What kind of city was Peja? What kind of people did it have?

Dilaver Pepa: Peja’s like Peja, a really beautiful city (laughs). As far as living back then… I lived in a neighborhood near Kapeshnica where actually all of us were… there was balance. We, as a family of traders, lived well, you know, we didn’t have any kind of financial problem. The conditions back then were, [I mean] education, you know, I am talking about former Yugoslavia, they were, as we know, school was free, healthcare was free. Life in general was good, you know, I can’t say we suffered some kind of consequence. Despite that, in the villages where they had, you know, the persecution of… allegedly the collecting of weapons, the surplus, and they struggled a lot, but as a child I don’t remember anything like that. We were an average family, you know, we weren’t very rich but also not… an average family in Peja. Actually, the entire neighborhood was like that, you know… plus the craftspeople lived a little better because they had income every day, you know, they didn’t wait to receive a wage at the end of the month.

And as far as I remember in Peja, back then there were plenty of factories, there were about ten factories. It was developed in general, you know… compared to the other cities of Kosovo, it was one of the most developed cities. And this is pertaining…

Anita Susuri: Maybe you were very young at the time, but do you remember the time of Ranković, I mean the ‘60s, ‘65, when people were fleeing. Do you have, how to put it, any kind of memory related to that…

Dilaver Pepa: I have memories from what they talked about, for example, because I was young at the time, it was ‘55, the ‘60s when a lot of people fled to Turkey. From my older sister’s discussions… actually my father always kept some letters and he put them in a… we had a metal box at home, he kept a journal there. After my father’s death, in ‘70 when he died, and then my sister went through the pages and showed us the letters… actually we had all the documents to go to Turkey, in ‘55, the year I was born. But my sister insisted, she opposed going there. She was a little older, 12 years older than me actually, she was about 15-16 years old, she was in gymnasium and she really opposed it. So, we didn’t go to Turkey. And as far as the time of Ranković, only from discussions, it’s not like I remember something like…

Anita Susuri: Yes, you were very young. I wanted to ask you a bit more about the store, you told me that when you started, you were about 15, but I believe even younger, I think you went to villages and photographed with your sister…

Dilaver Pepa: Yes, yes, yes. I started going to the store when I was five-six years old, I went there to clean and to… to help them with something, as children like to get mixed up everywhere. And my sister worked at the time, Lirije… She was one of the, I mean, my father, my father already started slowly leaving it to my sisters to lead the studio, so my two sisters, Lirije and Mersije. And I was, actually… back then it was called shegërt, to clean the studio in the morning… the condition of the wastewater system back then wasn’t good, the water… to get water… because the water for pictures has to be clean… replaceable. So, I spent my whole life, I mentioned earlier a bit, more in the studio than in the neighborhood playing with friends. When I became 14-15 years old, I already started to learn.

To go back to the question you asked me about the village… I was nine or ten, I don’t know, around that age… And they made some changes to the ID cards. In the villages in Dukagjin, it was kind of problematic for the women to come and have their pictures taken… you know, the situation was like that… more or less. And there came a… the head villager of Prilep as far as I remember, he was called Dulje, that’s what they called him. And while talking to my father… this was in ‘69, ‘68… I don’t know exactly now… “Can we come and have our picture taken?” He was aware that my sister was working and we agreed, with my father, with my sister… and my sister and I went there. I was a child, I would hold the backdrop, and help her with stuff.

And we started with the Prilep village, so, all the villages of Dukagjin, Prilep and on the way to Deçan and… Strellc and that way… the other area towards Pristina, Zahaq and these [villages], we photographed there. It was quite the job back then, you know, all the villages of Dukagjin, for documents, for ID cards. Quite the job and… and it was interesting financially because there was decent income. I remember like it was today, a TV… back then the TVs became a thing here. My sister, through that income, said, “Okay brother,” she said, “here is a gift, buy a TV.” Because there weren’t [many] TVs at the time, [it was] very rare. And this…

Anita Susuri: Did anything happen to you, for example… interesting or…

Dilaver Pepa: It was interesting, we saw all kinds of stuff back then, the villages weren’t developed like they are today. When we entered, what they call maxhe now where they prepared food, where… That was very interesting, you know… don’t let me get into details.

Anita Susuri: Were the differences noticeable, for example, the city from the village? Was it a big difference?

Dilaver Pepa: Oh, to… yes, there was a big difference because there was a… the villages were really neglected back then, I mean, the places where they lived. They focused more on agriculture, farming, so they didn’t place more importance on living [conditions]. They were, I don’t remember either now, the towers or the houses where they lived separately, some for women, some for men, where they ate, where they drank, where they prepared [food] together… like that. It was very interesting to me. In the cities it was different, you know, the conditions were a bit better, more… A person gets used to it, they adapt, you know, seeing it, it started to feel like a routine, it seemed the same.

Anita Susuri: What materials did you use at the time to develop the pictures? How did that process go? Where were those materials found?

Dilaver Pepa: Back then, at the time, I mean, there wasn’t anyone who worked with chemicals in Kosovo, with these… we usually got our supplies from Zagreb. Back then there was an enterprise which we called Foto teknika… Fotokemika, where they produced… the chemicals. It was the developer, the fixer, actually they call it the brightener now… different papers, the films, photochemistry. So, we would go there to get supplies. From sometime around the ‘70s, they opened a store in Skopje too, Zagreb’s Fotokemika. So, me and my sister Lirije often went to Skopje, to get supplies. There was the developer, the brightener, the paper, the films.

Back then the films were different, they weren’t like… you are young, I don’t know if you remember, film rolls, but they were made of glass, sets. So, it was difficult to find them but… when you continue the work you love, you find a way. The work with photography… at the studio it was quite difficult. There was the photography, after photography you had to take it, and develop that film. The film would develop and there was, as we say it, it was stressful… maybe they closed their eyes [in the photograph]. Because back then you didn’t see it as you do now… with digital [cameras], phones, “Ready… oh, the eyes.” Remove it, stop it, erase it. So, that was kind of stressful too.

When it came out well, then you had to dry the film. It would dry well and we would put it back in the camera. Then in the camera we had to, you know… to explain it, it’s quite the procedure. The paper goes underneath, the camera lets light rays through that film and the photography incorporates it. You take the photograph from there and you put it in the developer. Everything we are talking about is done in the dark room. There is a dim light, red, enough to see a bit. The photograph is developed there. You see that you got the results you want there and you put it in the brightener to stop the developing process because if you leave it for longer, it becomes darker, it’s destroyed. You put it in the brightener. You leave it there for some time, one, two, three hours, it depends, and then it’s flushed well. After flushing it, you take the photograph.

There’s an interesting thing people don’t know. We dried the pictures back then on glass. A piece of glass, for example, was one meter to half a meter and we cleaned that glass really well, we… actually with the powder used for babies, we put it there in order for the glass to shine. And we put the wet pictures on the glass. With newspapers, we had some rollers, they would call them like that, the newspapers were there to absorb the water. When we took out the water, we could see it and we would leave the glass close to each other, or somewhere warm or… in the summer we would leave them outside at home. From the warmth, the sun… and they would dry up, they would dry up, they would dry up and the photograph would show. So, it was a procedure that… then later on there were electrical machines. It was… they were… they had their plates, they would dry up, we would take them out.

Anita Susuri: Up to what year did you do that procedure?

Dilaver Pepa: I did this procedure until… now, I stopped in ‘74. Actually until ‘74, no… ‘78-’79… in ‘80 I already started color [speaks in English] photography. I mean, here because they started being done earlier. It lasted long to be honest, you know, I don’t remember exactly the year when, but… I remember in ‘85-’86 I purchased the first machines actually. They were for color photography. They called it dried photography at the time because they came out ready, from the system… from start to finish, they printed out the dried photograph. My brother, Skender, had contacted… some machines in Germany. The machines arrived. So, it started… the color time period.

Anita Susuri: How long did it take for the photo to come out? Until it was… when the final product came out…

Dilaver Pepa: I will go back in time a bit. How I first started… to learn the craft. It was a Sunday and on Sundays we usually would go out to clean the studio. Back then, we had wooden floors, we would coat them with different oils, you know, for cleansing. In the meantime, a client came, we wouldn’t work on Sundays, to have their photo taken. Now I… I don’t remember if I was ten or 12 years old. He said, “I want to have my picture taken.” I would think of how to photograph him and he needed the photos quickly. And I took the courage and said I’ll try, if anything comes up I would either call my sister or my father and tell them. I took it, we had some light [speaks in English] cameras. At the time they were cameras the size of the palm of your hand. We would put the film… the film… there were already film rolls. We would put the film… I photographed him. And then I told him, “Come back after an hour, after an hour and we’ll see.” He left, [after] I photographed him. I quickly cut the film. A small piece of the film and I developed it. And it was great, it came out well. So, since then I started the craft of photography. And then they started to assign me stuff that I could work on which was a little more simple.

Anita Susuri: For example, how long did it take…

Dilaver Pepa: It took… for a photograph to develop. For example, washing the film lasted five-six minutes. Then there was the process of drying, until it dried, that took a long time if you didn’t have… back then we didn’t have hair dryers to dry them, for example. But we had to leave them somewhere warm, near the stove or something when it was winter. When it was summer, we exposed them to the sun a bit. While the process of photography… working on that lasted for about half an hour too… development, washing, drying. So, about an hour, I mean, taking a simple photograph, about an hour, two hours, that’s how long it took…

We usually took pictures during the day. In the evening we would take them home and at home… I explained that procedure with the glass earlier… and… in the evening we would put them there to dry. When we woke up in the morning, we would take the pictures that had fallen from the glass, we would collect them and go to the studio. This was the procedure. I actually worked in the studio until ‘81. That’s what it was like… because in ‘74 when my sister came to Pristina, they called her at the Faculty of Medicine to work as a photographer. It was me, my sister and my brother. It was my second sister, Mersije, my brother and me at the studio. In ‘78 I went to military service, in ‘79 I finished it, in ‘80 [I worked] at the studio, in ‘81 I came to Pristina for work.

Anita Susuri: Before going there, I have one more question about the studio in Peja. At the time, were there many demands for photography and… you mentioned ID cards and…

Dilaver Pepa: Yes…

Anita Susuri: …documentation, but also… what else did people have their pictures taken for?

Dilaver Pepa: Besides documentation photos, they came for… to take engagement pictures, even marriage ones because back then people didn’t go to weddings to take photos, but after they got married they came [to the studio], usually it was the whole family. I don’t know, I mentioned earlier, it was quite the ceremony to have photos taken. They prepared one week ahead, they bought new clothes… because they didn’t wear just about anything for photos. So, it was a procedure that… the studio was… it had its own workshop. So, men, women, children, and whole families came to take photos. It was a good job, you know, it wasn’t too much effort, but it was a good living.

And then we had… the military… Back then there were the barracks. And they would usually go out on Saturdays, Sundays, the soldiers. And I would have to go [to the studio] because they came to take photos… they had a memory from the military. Back then we made photos… there was a template… it was in Serbian, for example, what do I know, “Memory from the People’s Army of Yugoslavia” at the time. And there was enough work on Saturdays and Sundays, you know, with the soldiers. And then my father would go out… in Peja there is a big park, a beautiful park, they call it Karagaç, it was a very beautiful park. On Sundays families would call him to photograph them in the park… so, that was the job. When it comes to amateur photography, as we call it, for example, people who took photos themselves, that started later on… there were no conditions to own a camera at the time. But, after some time there were cameras, films, work with different amateurs started and that’s it.

Anita Susuri: In high school, what school did you attend?

Dilaver Pepa: Gymnasium Sami Fr… 11 Maji, now Bedri Pejani. That was a school… I remember a case when some Peja natives came from Albania, people who had run away and they managed to come back here. Back then Albania was… I remember it a bit from memories, from discussions… Peja’s gymnasium at the time was like finishing a university, you know, it was a good school when it came to education, the professors, and even the students. They were a little better than now, I am talking about the present situation. I am a bit critical, you know… so many schools have opened, but the quality isn’t… and from the gymnasium in ‘73-’74 I enrolled in the Faculty of Law…

Anita Susuri: In Pristina?

Dilaver Pepa: Here in Pristina. Actually, I have been in Pristina since ‘74, there were some interruptions. I mentioned that I went to military service in ‘78, in former Yugoslavia, I finished it in ‘79. I left university a bit behind, I had to go back to the studio again and help out, work… until ‘81. In ‘81 I came to Pristina. I…

Anita Susuri: So you ultimately settled in Pristina in ‘81…

Dilaver Pepa: In ‘81…

Anita Susuri: The studio…

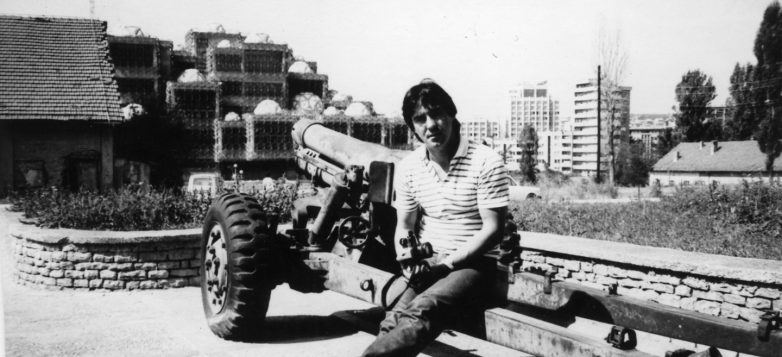

Dilaver Pepa: Yes with… no, I was working in ‘81. It actually connects to the demonstrations. On April 1, in ‘81 we started work when they called us. That day there was a massive demonstration in Pristina. I came in ‘81 and was actually here close to Dardania [neighborhood]… the studio I have now, I saw the row of buses, they were in a line. And I thought to myself, “It’s the first [of the month], they Ramiz Sadiku [enterprise] workers are probably receiving their wages.” When I took a few steps further, I saw the crowd of demonstrators, at that point… it’s known that ‘81 was… the massive demonstrations in Pristina, on April 1, April 2… we started work that day, they called me at the Museum of Revolution.

Anita Susuri: What else did you see… was there a lot of police presence, violence… What was there?

Dilaver Pepa: There was everything. There were many policemen… the crowd was so large that… not even the policemen were noticed because of the large crowd. But when they started throwing teargas, and even [shooting] real bullets, that’s when people started panicking. People started running away, to… I came here, I had to find my sister’s apartment, because Lirije had already settled here in Pristina in ‘74. I knew it, I was there several times, but one gets confused in that kind of chaos. But I found the apartment, and I went there. And then I couldn’t go out anymore. Anyway, my curiosity prompted me to go out and see what was happening, you know, but they didn’t let me go out that night, because it lasted until late at night, the demonstration.

The next day we had to be present, on April 2, we had to go to work. Actually there was a meeting, the director, the former director, Muhamed Shukriu had invited us. But the situation was… until I managed to leave the apartment, back then… we lived near the roundabout, and our meeting was near the Stadium of Pristina. That’s where the Community of Culture was, they invited us for a meeting there. On the way, [there was] broken glass, vehicles… broken cars, the police had shot everywhere. Yes, {shrugs} it was chaos, a great chaos, so, we slowly started working.