Part Two

Anita Susuri: You told me that you didn’t immediately finish high school but you continued, you started working in the mine although the mine was far away, so you walked for an hour and a half. And it was the ‘70s, ‘74 when Kosovo’s position improved a little.

Avdi Uka: Yes.

Anita Susuri: I mean, the Constitution…

Avdi Uka: Yes, yes of ‘74.

Anita Susuri: What was the situation like at the mine at that time?

Avdi Uka: Back then it was really good. You traveled, the bus, they launched some lines at certain places, I mean down south around Mitrovica they already had them, but not us there in Shala, they suddenly launched vit-vit-vit {onomatopoeia}. They laid asphalt in our area, from my village to there, and then after the bus [line] launched we would walk about one kilometer by foot, we would go to the shore, [walking] on asphalt, it felt like we weren’t working. The salary was really good, it was really good, life was good.

And with those amendments of the Constitution of ‘74 we had many rights, many rights. What we didn’t have, we didn’t have our own army and police separated and we didn’t have the title Republic, but with those amendments of the Constitution we were whatever we wanted. Now imagine that an Albanian should’ve been the president of Yugoslavia. And there was, and there should’ve been according to the Constitution of ‘74, and it was. Come on, come on, come on, come on, it was good.

Veli Deva, whoever heard of him, when he came to Trepça, he was a mine doctor. Imagine in the time of Veli Deva, we received our salaries with two lists, with two lists. Because he couldn’t put the salary in one list because it was too high, so he divided it in two. He would give you one portion here, one there, so you had enough money, I am talking about Veli Deva’s time, yes. Later there came Aziz [Abrashi] and Burhan [Kavaja] and these directors, it all depends, even the directors played their role.

The union would help with children’s books, they gave me a bag full of children’s books and notebooks, the union. So, the situation was improving, it was repairing and stuff. They started building buildings, Veli Deva built the buildings in Tuneli i Parë and had promised to build buildings from the mine to Shala. The Trepça workers who wanted an apartment would be given the keys {pretends he’s giving something}, the ones who didn’t want apartments would take credit, they would call it, long term, 30 years, 40 years, to give them the credit, to make it possible for miners. But that didn’t last, they smashed it, removed it, ruined it, and what happened, happened.

Anita Susuri: What type of work did you do during the time at the mine? What was your work like?

Avdi Uka: There is no work… my work was, there is no type of work in the mine that I didn’t do and I extracted ore and I excavated the ore and I fixed the railroad for the wagons to move on and I drove the locomotive to transport the ore. There is no work in the mine that I didn’t do. I worked with pipes too, with water pipes, the water supply or what do they call it because there everything is with water, the machines have the water and the air and everything. There was no work during those years that I didn’t… work there. My last position for about thirteen-fourteen years was that of a miner. The salary was good, the work was more difficult, riskier, but very well, the salary was really good. A crowd of children, ten children and my wife, twelve members of the family lived on that salary. And we had to ask for a bit of extra money.

Anita Susuri: What year was it when you went to military service, I mean you mentioned you started working, and then you went?

Avdi Uka: ‘64, I completed military service in ‘65.

Anita Susuri: Where were you for the military service?

Avdi Uka: Where was I for military service?

Anita Susuri: Yes.

Avdi Uka: I was in Paraćin first, in Paraćin. In Ćuprija, in Banja, in Kremna, I was in five, six places for a bit. They sent me to [give] commands, I don’t know what they called it. But first in Paraćin, for about six months.

Anita Susuri: What was it like back then?

Avdi Uka: Look, I said it in the beginning and I will say it again, back then there was no bigotry between nations, Albanian, or shka, or Bosniak or Turkish or what do I know, there wasn’t. Actually, actually, actually at the time when I was [working there] we had great advantages because the officers themselves told me when I went to Banja, it had seven guards, guard places {moves his hand in a circular motion}, guard places.

The officer would tell me, he would say, “When you’re under my guardianship, I,” he would say, “sleep comfortably” {rests his head on his hand}. They had full trust in us, because there was no Albanian that didn’t go there and catch the asleep, or to take their gun (laughs) or something. They had trust and we had advantages, there was no, there weren’t these grudges and bigotries between each other, at the time when I was there.

Anita Susuri: Did you have visits, did you go to visit your family? What was that like?

Avdi Uka: I was once, for a month, not an entire month, I was on a break once. My brother came to visit me once, for like a day, twice, once one of the brothers and then the other, they came to visit me, there were no obstacles. We went out and strolled around the city, they went back home, we went back there.

Anita Susuri: Was it the first time you traveled in Serbia when you went in military service, or other places of Yugoslavia? What did traveling seem like? I think [you traveled] by train?

Avdi Uka: Yes we went by train, we went by train. But very well, even before I went to military service, before going to military service, I was young, I went to Belgrade by train. I was in Zagreb too, I was also in Ljubljana, I mean before going to military service as a young man.

Anita Susuri: What was traveling by train like back then, what was the place like?

Avdi Uka: Honestly I will tell you the truth, maybe someone sees it as a big deal, to me it was some kind of joy. You were free, you went into the cabin, you got your ticket, you sat down, nobody bothered you, you arrived and went out. Whatever you went there for, I mostly went for visits, to visit some nephews and [maternal] sebep like that, I went on some military visits, I didn’t have any problems anywhere. We went, I did my business, I returned, there were absolutely no type of problems.

Anita Susuri: Back then it was normal, I mean, to visit other places…

Avdi Uka: Yes, yes, yes, wherever you wanted.

Anita Susuri: You had no problems.

Avdi Uka: No, that’s right, you had no problems back then at all. Just like sleeping in the middle of Belgrade, or in the middle of Mitrovica, it was the same.

Anita Susuri: No, I wanted to ask you about when you created your family, when you got married, how did the marriage come about? Did it happen after military service, or?

Avdi Uka: Yes, after military service, I was at work, my brother, back then we didn’t find our wives by ourselves. My brother found my [now] brother-in-law, found the bride, sent the msit, when it was my turn [to get married] among my brothers, it [the tradition of msit] was still current. A village there above ours in Bajgora, in Shala of Bajgora, my wife is from the village Bajgora. It was like that for about six or seven months, working on some stuff here and there. At that time I was working in Trepça and had my salary. I will never forget it, [it was] 800 dinars. When I went to Turkey, in Istanbul I got eight lira {touches his neck} with my salary, today a lira costs 350 euros or how much, I am not sure…

Anita Susuri: More.

Avdi Uka: Back then it was a hundrder dinars, my salary was 800 dinars with no qualification, no qualification. And I went, I went to Turkey, I bought working tools. Despite everything I never said I did anything but my brother, because back then when we received our salary, they gave it to us in an envelope, in an envelope, the ration stamps and the salary, as soon as we got home we gave them to our big brother, head of the house, he took out the ration stamps, gave them to us, and a little money, have a nice day, have a nice trip. He led with it, we weren’t concerned with that.

Anita Susuri: What about your wife’s family, were they perhaps miners too?

Avdi Uka: Her father, my wife’s father was a miner too, he was a miner too.

Anita Susuri: So, there were many families who formed relationships like that.

Avdi Uka: Yes, exactly like that. I said that Shala, Shala, Shala has 36 villages as we’re referred to as up there, so there is no person that didn’t have from one to five [family members working] in Trepça. They were all working in the mine, and they all traveled by foot. There were people from Llap, from Drenica, from everywhere. But the ones who were from around the neighborhood slept in ban haus [Ger.: residential building] they were ban haus as they called them in German.

They slept there, when there were a couple of days off, they went from home. The ones of us who were in the surrounding area traveled, all of us went back to our houses. My father-in-law worked in Trepça too, he died sometime around ‘82. He was a miner, he died, he got ill, he passed away. And my wife is from that village. I mentioned that my brother found my [now] brother-in-law and until the night they brought her here and she got out of the car, I did not see her at all. When she got out of the car, it seemed like I didn’t see the Sun anywhere else but in her (laughs). She wasn’t here because my wife is very good. (laughs) Say something because I am joking a little.

Anita Susuri: No problem. I wanted to ask you about your family while you worked, you’re saying that your father-in-law was a miner, but were your wife and children worried when you went to work, that they weren’t sure what might happen?

Avdi Uka: Honestly not only my family but every member, every family, each and every one of them were in fear until they [the miners] went back home. If something might happen to them, as I mentioned [there were] nine cases, I was in the village where exactly a person from my village lost their life in the mine there. And at 12:00 PM we were notified, they said, “An unfortunate…” in the transistors, there were no televisions back then, nor was there electricity in my village, and they said, “This person lost their life.” All felt pain, all felt sadness, all felt fear, the entire family. While we, I said we got used to it, we weren’t bothered at all, [but] the family were loaded [with stress].

Imagine there was a case, my father had his oda on the second floor {describes with hands}, there was a window with a street view where [they] would come back by and when the winters were windy, back then the winters were harsh, I wasn’t working [yet]. “Look father because the miners are coming” as he said. Because they would come back walking down that street, 15, 16, 20 workers would leave work. “Father they are walking down” “Oh thank God!” {puts his hand above his heart}. And without even having a family member [of his own] working in Trepça, but for the fellow villagers, not for family members, that’s exactly what it was like. Everyone had the fear that something might happen [to them] at work or what do I know.

Anita Susuri: Were you ever at risk? Were you at a high risk?

Avdi Uka: I was at risk a hundred times, the ore fell down in front of me, in front of me {moves his hand near his face}, tonnes [of ore] fell down. The wagon ran me over, at the grizë where the ore is unloaded, it’s unloaded and it crosses through a bridge and the wagon unloads, my foot was there, two of my toes are broken. My toes were in a cast for over a month, God protected me, and those two toes are broken to this day. They remained the same way they were put in a cast, my toes.

We had a bit of injuries, nothing big, some had big injuries, there are people who have lost their legs, there are people who lost their hands, there are people who lost their eyes. I mean everything happened there, everything happened. I had that injury back then, my brother had the same system, his hand {touches his finger}, my big brother broke his finger, the others [had] no [injuries]. We didn’t turn them into big deals at all, you know those small injuries, minor injuries, there was no risk.

Anita Susuri: You had your insurance, did they immediately send you to the hospital?

Avdi Uka: Immediately, immediately, immediately, immediately, and nobody asked for a dinar, nor [did I have to] give it to them, all the doctors looked after you, you had every single thing in the hospital. They healed you, they let you go, they gave you medical time off, to rest a bit afterwards, to heal and stuff, it was paid time off. Now they say [medical leave] is up to 20 days, 15 days, I don’t know what it’s like now. But back then if the doctor and the commission of doctors gave you two years, you had two years bolovanje [Srb.: medical leave] and it was all paid {pretends he’s writing something}. There was no problem, absolutely not, it depends what kind of illness or injury you had.

Anita Susuri: I wanted to ask you, I don’t know if you remember the first time you went to the mine, what was it like?

Avdi Uka: I will honestly tell you the truth, it seemed very interesting to me, I worked in Fafos for two years, in fertilizer production. Trepça took Fafos, took it under its management and made a request, “Can I not go to Mitrovica for the sake of not traveling,” since Trepça was closer to me and they immediately transferred me there. When I got inside on August 15 in ‘67, I would look and it seemed like I was in a different world. Those corridors made of stone, the workshops made of stones, the offices, the supervisor office all made of stone, so I would look (laughs) weird.

What they did, back then the supervisor sent you along with an older worker, they said, “Take him as a helper.” First they sent you to do some easier tasks, for a week, for a month, just as an example, that surely happened. Now with the amount of months increasing, your job position increased too and you went straight into production. They don’t immediately send you to the dangerous sites, slowly learning, while observing, observing and… but very interesting, very interesting, just like seeing a movie or like something you’ve never seen before, it was like that. You have seen a hundred movies, but you stumble upon one you have neber seen and it seems so interesting. That’s how that was, it was very interesting.

Anita Susuri: Did it ever happen to you for the lamp, that [helmet] light to stop working?

Avdi Uka: It happened, it happened for a very short time, or you had to go to the side until a friend, a coworker comes. Or you had to go up against the wall while touching it, to not go onto the railroad because if the locomotive or something came it would grind you, so [you had to walk] very slowly. It happened for very short periods of time and the thing is that in the mine it happens very rarely that you are alone. You’re always with another person, or two other people, or another person, if my [helmet] light stopped working, yours didn’t, with that lamp you got out, yes. Those things happened, they happened. But when my brother worked, they worked with a carbide [lamp] as they called it, carbide lamp, they put the carbide on, the water lit it up frzh {onomatopoeia}, that wasn’t safe/reliable at all, but they had it on, there. When I started working there was {puts a fist near his forehead} the battery ones, you hung it on your waist, the other one on your forehead {touches his forehead} and it was, it was well, yes.

Korab Krasniqi: Did you communicate there…

Avdi Uka: {Gets closer to hear better}

Korab Krasniqi: Did you communicate only with the friends you were there together with, or you could communicate with others from different sites too?

Avdi Uka: No, on that level, on that level, one level, for example I worked on the eight level, I’m taking it as an example, because I worked on many levels, one level had at least 13-14 workshops. They call it a workshop {describes with hands the room where it’s located}, you and your helper drilled [for ore] here, I drilled there by the doors, the other one drilled somewhere else. And when you received the work timetable we were 40 people sitting in one place like this on klupa [Srb.: desks]. The supervisor got up, “You will go to this workshop, you, you to that workshop.”

When some days passed, a day, two-three days, he would just say, “You [go] to your place, you [go] to your place” and everybody knew their place. If something changed or if a workshop got removed and another new one opened, they gave you the timetable together with another person or two people. Because the miners had their helper, the one who loaded the ore was someone else, many times, many times he had a helper too. So, four people came to a workshop here, my helper and I drilled here {points to the right} you and your helper there {points to the left} you took the ore and loaded it. So, we were always in contact with friends.

Korab Krasniqi: Did the condition differ from one level to another, for example?

Avdi Uka: Hm?

Korab Krasniqi: The conditions, the work conditions…

Avdi Uka: Yes.

Korab Krasniqi: Did they differ from one level to the other?

Avdi Uka: Nope.

Korab Krasniqi: Is the air, does it differ…

Avdi Uka: The air, the air differs a little, the higher levels or the south, I’ll take the south as an example where the air is heavier, the air [feels] closed [in], heavier. The north is clearer, there are levels with different air, there are levels with different [air], but they differ only a little, the air differs a little, they differ a little, they differ a little.

Korab Krasniqi: What did you fear the most when you went down there? Was it the earthquakes, or the landslides or what risk did you fear the most?

Avdi Uka: The most, the riskiest, every one of them, they are all, whatever happens there, whatever happens is a risk. But very well, we feared the most and the riskiest were landslides, because we had these workshops, there are workshops almost one hectare, do you know the size of one hectare? Very large. And you don’t know {points up with his hands} what’s happening up there, you extract ore up to four meters, five meters, and that’s left, the ceiling is left like this, all stone, what do you know, it can happen once.

In my workshop, where I worked during the first shift, the second shift, back then there was no third shift at all when I started working, only two shifts. The first and the second. Then when we went from the second shift, we would go to the first shift, when we arrived the entire ceiling fell down on the ground, the entire ceiling. Around two meters thick, we drilled that for five-six months straight, we loaded the ore, we extracted the ore from that. In case it pinned us, maybe it would take a month to get us out of there, breaking [down the rubble] and then getting us out, yes. That’s the greatest risk there, but they are all risky, they are all risky.

Now, seven meters, seven meters, seven flights of stairs, each four meters, have to be climbed to the workshop, the machine in your hand, the munition on your back, I am taking them as an example, sometimes the machine, sometimes the munition. God forbid if one of them broke, you would go down, so the risk was everywhere. But very well, as I said one gets used to it and you practice and stuff, but the greatest risk from which you couldn’t be cautious about were landslides. You’re cautious about everything, you are careful, but you can’t [be careful] against that, because you don’t know {points up} what’s there.

[The interview was interrupted here]

Anita Susuri: Mr. Avdi, Avdi, I wanted to ask you about the ‘80s, the student demonstrations began in ‘81…

Avdi Uka: I know it very well.

Anita Susuri: And the situation started becoming worse…

Avdi Uka: It got worse, yes.

Anita Susuri: What was it like there in Trepça at that time, during those years, how did you see it?

Avdi Uka: In ‘81, the demonstrations of ‘81, it began on March 11 of ‘81 in Pristina. Personally, as Avdi, I am not saying I am somebody, but as Avdi I said that if it is, it is good. Why is it good? There are rumors that they were organized by somebody else, rumors, I don’t trust them much. I had discussions with some former leaders of that time, ours [as in Albanians], “This and that, they were organized by this and that,” I said, “Sir I absolutely do not care who they were organized by, I am interested in a Kosovo Republic, who is against? I am not against that.”

Do you understand, to put it briefly, Kosovo Republic, okay, I support it. But very well, as we all know how it happened, how it was organized and stuff, they started come on, come on, come on and they brought the police special unit, they cornered Kosovo. The Mayor of the Municipality of Mitrovica and the director of Trepça: Shahin Bajgora, Shahin Bajgora [was] Mayor of the Municipality of Mitrovica, Shyqyri Kelmendi [was] director of Trepça, we were working in ‘81, vërc {onomatopoeia} this vërc {onomatopoeia} that to bring the police, for the police to watch us there.

Anita Susuri: In ‘81?

Avdi Uka: I am talking about ‘81, about ‘81.

Anita Susuri: Yes.

Avdi Uka: They said, “No,” those two. “Policemen can’t come here,” besides the small [police] station that was there, it was in Trepça, a small [police] station for Shala and for Trepça. “He saw it himself. You shouldn’t bring foreign police here, because we have our people, our workers for National Security” or what were they called, I honestly don’t know, they put two hundred of us, miners dressed in military uniforms. And we did rounds in Trepça, I mean to make sure nothing happened, [to make sure] nobody came. A rule is a rule, law is law, our leadership agreed to do it like that, we had the guns there at the enterprise. Every enterprise had its guns and every person who was part of the defense had their gun, and they put us [in uniforms].

Anita Susuri: How did they choose who will work on defense, or just like that, whoever was more trustworthy?

Avdi Uka: Absolutely, the Trepça leadership, the union, the director, the Trepça leadership should’ve been, I’m taking it as an example, 200 people, 1300 miners, 200 of them should be for defense. They appointed this person, this person, that person and it didn’t matter who, they were all the same, but very well someone was picked. And they put us [in uniforms], I myself was wearing [the uniform] there in ‘81. I would be surprised, I would wonder why they were paying us, what they were paying us, what we were doing, we didn’t do anything, but very well, you would go there.

There was the enterprise guard, even today there is a guard, they would send a guard and a soldier at the office where the offices were, they called them a porter or what [were they called], they were just a guard there, they sent a soldier too. And that’s how they doubled it, where there was one they made it two, where there were two they made it three and they made rounds, nothing at all, absolutely. Anyway it was well, Trepça at that time wasn’t affected, at the time, in ‘81, let whoever say whatever, Trepça remained, how to put it, like, like it was sleeping, I don’t know how to put it, maybe it should’ve woke up. But very well, Trepça didn’t wake up and that passed, yes.

Anita Susuri: There were those slogans “Trepça works, Belgrade builds…”

Avdi Uka: Yes, yes, yes, yes “Trepča radi, Beograd se izgradi” [Srb.: Trepça works, Belgrade builds], that’s right, that was it and it was exactly like that. Why, what was melted… the flotation [mine] was in Zveçan, it came out of Trepça and it was grinded, it went here and there, it was melted there, they made gold, whatever was gold was packaged and all went to Belgrade. At the time it all went to Belgrade. Eh, there’s rumors, there’s rumors, there are rumors that up to four thousand kilograms of gold were extracted each month.

400 always, but [there were rumors it was] up to four thousand, now it depends. And it all went to Belgrade, and all the lead and zinc, Belgrade sold all of it, wherever they wanted, however they wanted. Eh, they sold it and some of the money went for your salary, to buy some tools or something, the other they used for themselves, have a nice day. And that slogan was exactly like that, that Belgrade “Trepča radi, Beograd se izgradi” [Srb. Trepça works, Belgrade builds], that’s right.

Anita Susuri: Did that bother you, was this something that pushed you more towards expressing your dissatisfaction?

Avdi Uka: Yes it was, of course it was, since then, look from ‘81 it almost got that… {moves his hands to the left}

Anita Susuri: Direction.

Avdi Uka: The other direction, the complaints, the demands, someone more loudly, someone less loudly. And God brought it, when it came to ‘88, ‘81, in ‘88 trouble broke out, Trepça stood up, old and young, the entire Kosovo, not only Trepça, the entire Kosovo on their way to Pristina, in the Boro Ramizi hall, and at the center and the stadium and what do I know. And like that, on February 20 of ‘89 we went into strike that day for the first time, God brought it…

Anita Susuri: When you got on your way to Pristina by foot, what was that day like, how do you remember that day, how did it all go?

Avdi Uka: That day went, because these… look even those Serbian gatherings, they gathered in Kosovo.

Anita Susuri: The meetings.

Avdi Uka: They said all sorts of negative things about Albanians. Belgrade would send letters, all sorts of negative things about Albanians. To take away the right of language, the right of education, for the education workers to retire prematurely, prematurely {raises his index finger}. For the leadership of Kosovo to not be elected by us, but for Belgrade to elect it, whoever they wanted. That was the breaking point and we went to Pristina, we discussed, I myself spoke at the Boro Ramizi hall, bam-bum-bam-bum {onomatopoeia}, we couldn’t do anything, nobody took that into account.

Anita Susuri: I think when you got ready to go there you had a photograph of Tito, Yugoslavia’s flag…

Avdi Uka: Yes, yes, yes…

Anita Susuri: How, why like that?

Avdi Uka: I will tell you why Tito, I swear to you, I don’t want to complain either, just reality, I don’t even know why, what, who took it, you understand? But there was talk and we took it, I am saying that I agreed to take it too, I am saying it wasn’t my decision but very well, we took it. Why we took it, Tito was dead, there was nothing of him, for what, there were checkpoints, police checkpoints and you didn’t believe that you could manage to walk to Pristina, that they would allow you to go. As a justification, look we are showing Tito in the front {pretends he’s holding something with his hands}, he was dead there was nothing of him anymore (laughs).

But very well, they took it, they didn’t do anything bad (laughs), let anyone say whatever. They took it, you can take a dead person anywhere, a dead on, don’t take a live one (laughs). People lived for 50 more years, we lived in that system, honestly yes. They took it, it wasn’t a big deal, just for the sake of police checkpoints, in case they attack you, if the police attack you, to say, “Look at what they’re doing, we have Tito’s photograph and they are attacking us” to blame it on them, not just us who took it.

Korab Krasniqi: Did you believe, excuse me, did you believe in Yugoslavia back then?

Avdi Uka: Absolutely not, we didn’t believe in it.

Korab Krasniqi: What did…

Avdi Uka: Back then neither… hm?

Korab Krasniqi: What did Yugoslavia mean to you? How did you understand Yugoslavia?

Avdi Uka: We understood it, I said that since Tito’s death, since Tito’s death, Slloba [Slobodan Milošević] and Slloba made his people do every bad thing in the world to Albanians. As I said, instead of somebody else retiring early, for example miners, he made the education staff go to early retirement. To get rid of them so children don’t learn Albanian. The Albanian leadership, Kaqusha [Jashari], Azem [Vllasi], and everyone, whoever was [in the leadership] back then, I don’t know who it was, I mean to fire them and send whoever they wanted, Serbia. And then we stood up against them.

The amendments of the Constitution of ‘74, I mentioned earlier that you had everything, you didn’t have the title of republic, you didn’t have a separate army, but you had many rights with that, they revoked it. They revoked the amendments and they wanted to take us a hundred years back, backwards, take us a hundred years backwards. And we went on strike and the demands were this, this, this, nine demands. So, they were all known prior to it because we held a hundred gatherings. They came to the Committee, we spoke in front of them, we spoke in the Boro Ramizi hall, we spoke in Trepça’s hall, they absolutely didn’t care.

To look at and review the demands, this, this, that, they put them in a drawer and didn’t share them anywhere. And the people reached a boiling point and we said it first, “We don’t give Serbia one shovel of ore, we won’t anymore until our demands are met.” The United Nations to look out for Albanian people’s fate, they mention the United Nations today, God sent it, before 35 years we mentioned it and I served exactly 14 months in prison for that work, because I said it, that the United Nations [should] look out for Albanian people’s fate. And many, many others I mean.

Anita Susuri: What about that day when you got on your way [to Pristina] by foot, what was the journey like? I think the police stopped you?

Avdi Uka: At many points yes, they stopped us at many points, they asked…

Anita Susuri: What was that…

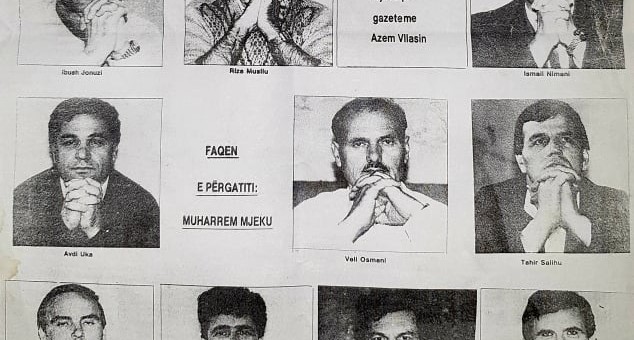

Avdi Uka: And there was nobody who could hinder the power because there were many workers, a lot, au, au {onomatopoeia} stop there, step aside, they had no way but to clear the way. And kërk {onomatopoeia} [people] came into the hall from all sides, the entire Kosovo, whoever heard about it, whoever could, whoever… the hall filled with people. When I entered there were millions of people there, standing room only. I asked for the floor and I got up and spoke. And when they judged us [in the courtroom] they put out my photograph, I am telling the truth, if I had that photograph exactly as it was, I wouldn’t have given it away even if you paid me five thousand euros.

Anita Susuri: But you didn’t find it?

Avdi Uka: Nope, UDB took that. But that photograph, that talk, in Trepça when Stipe Šuvar was there, I talked to him in Albanian, Remzi Kolgeci translated it although I could’ve said it in Serbian, I didn’t want to, on the eighth level I spoke in Albanian, just out of spite, I talked in Albanian out of spite, eh. I could’ve said everything I said in Albanian, I could’ve said it in Serbian but I didn’t want to.

Anita Susuri: What about when you entered there, how did you think about speaking among all those people? They gave you the right to speak or you asked for it yourself?

Avdi Uka: I asked to speak because in Trepça it’s bad to say I…

Anita Susuri: I am talking about when you went to the 1 Tetori hall.

Avdi Uka: Yes, yes, among the miners of Trepça I enjoyed full trust and nobody said a word when I spoke, nobody breathed and they always gave me the floor, I had privilege, always. And it’s not that I only spoke at the strike and in Pristina, I always spoke, always, always, always, always. Always, always, always, always, eh. They took me to the police station and held me there for five, six hours a hundred times, a hundred times. They called me and asked, “Look, what are you lacking? What do you want? Do you want an apartment? Do you want credit?” As I said [I was] 40 years old, “Why? What do you want?” {places his hand to his heart} “No, I don’t need an apartment, nor credit. The gathering was called, I can speak about my rights. I have the right to speak. Don’t call the gathering and I won’t speak.”

Korab Krasniqi: Do you remember what you said at the hall? Who did you talk to and what was the topic of the discussion when you went to the 1 Tetori hall here in Pristina?

Anita Susuri: What did you talk about?

Korab Krasniqi: What did you talk about, do you remember?

Avdi Uka: About all of these, about our rights, about our rights.

[The interview was interrupted here]

Avdi Uka: I said in the beginning that those, those things that Serbia did, that Serbia did, directly, anyone can say anything, they can sell spurious patriotism, we weren’t against Serbians, against Serbians, we were against the politics of Serbia, against the politics of Serbia. Three members of the Committee, 200 miners were in the hall when in ‘87, in ‘87 I asked, I said, “I entreat the Central Committee…” I was never a communist, I never joined a party. I am a miner, I am Avdi Uka, I am a retiree, but very well, I asked and said, “To take Slobodan Milošević and send him to a doctor, if he is sick to give him medical help. If he is not sick and he is doing these mistakes or these intentionally, or these, or this oppression of Albanian people, he should be hanged at the Ibri bridge.”

Three members of the Committee were sitting there, the entire Trepça leadership and there were 200 and more miners sitting there when I said that in ‘97 [‘87], ‘98 [‘88]. I mean always, we always spoke, we always spoke seeing that he was causing trouble among Albanian people, and removing our rights. And now the discussions, it depends what he said there, we answered here, with gatherings, and going to Pristina, it was all these demands, why would the Albanian education staff retire, why go to early retirement? For what? That you were lacking, and they wanted to send their own. Why should Serbia elect Kosovo’s leadership when we could elect them ourselves. We should choose ourselves, this person, this person, that person, this should be a minister, this person here, that person there.

So, they didn’t want that. They would go to Serbian gatherings, “Albanian women are whores, Albanian women give birth to ten children each,” they insulted my wife and my mother, “You made ten irredentists.” I didn’t know what an irredentist meant, I am telling the truth I didn’t know, I didn’t know what irredentist meant. I knew my people’s rights, society’s rights, to demand my rights. Never for myself personally, because I told you that if I wanted, if I wanted I would’ve gotten an apartment wherever I wanted, only if I closed my mouth {puts his hand over his mouth}. I didn’t want to get one, why, what do I need an apartment, why do I need credit?

A bite of food, I managed through my own sweat {wipes his forehead}, with my work and I want to be honorable to God first and to society. One who is a [decent] person, they know, they know that you can never be honorable. All the trouble by Serbians, they started killing the army. They killed Aziz Zhazha in the middle of Paraćin, I was in that kasarne [Srb.: barrack] before him. They killed {pretends he’s holding a gun} the soldier. What kind of person is that who kills their own soldier in uniform. They took him there to serve and they killed him at night while he was asleep, and many, many others. And it reached a breaking point and there was no way but to stand up, there was no other way. And that’s how it reached a breaking point dub dub dub dub {onomatopoeia}.