Asphalt for Progress

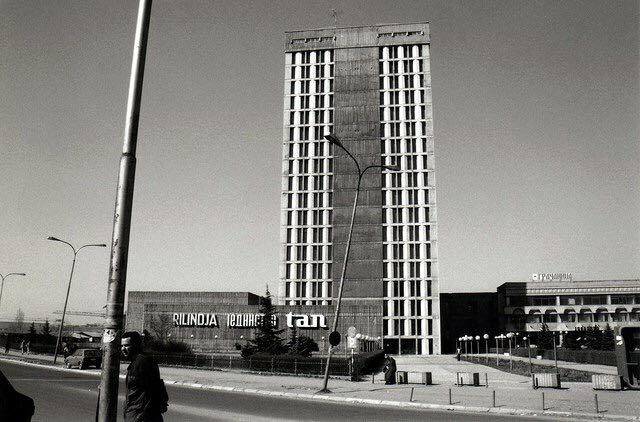

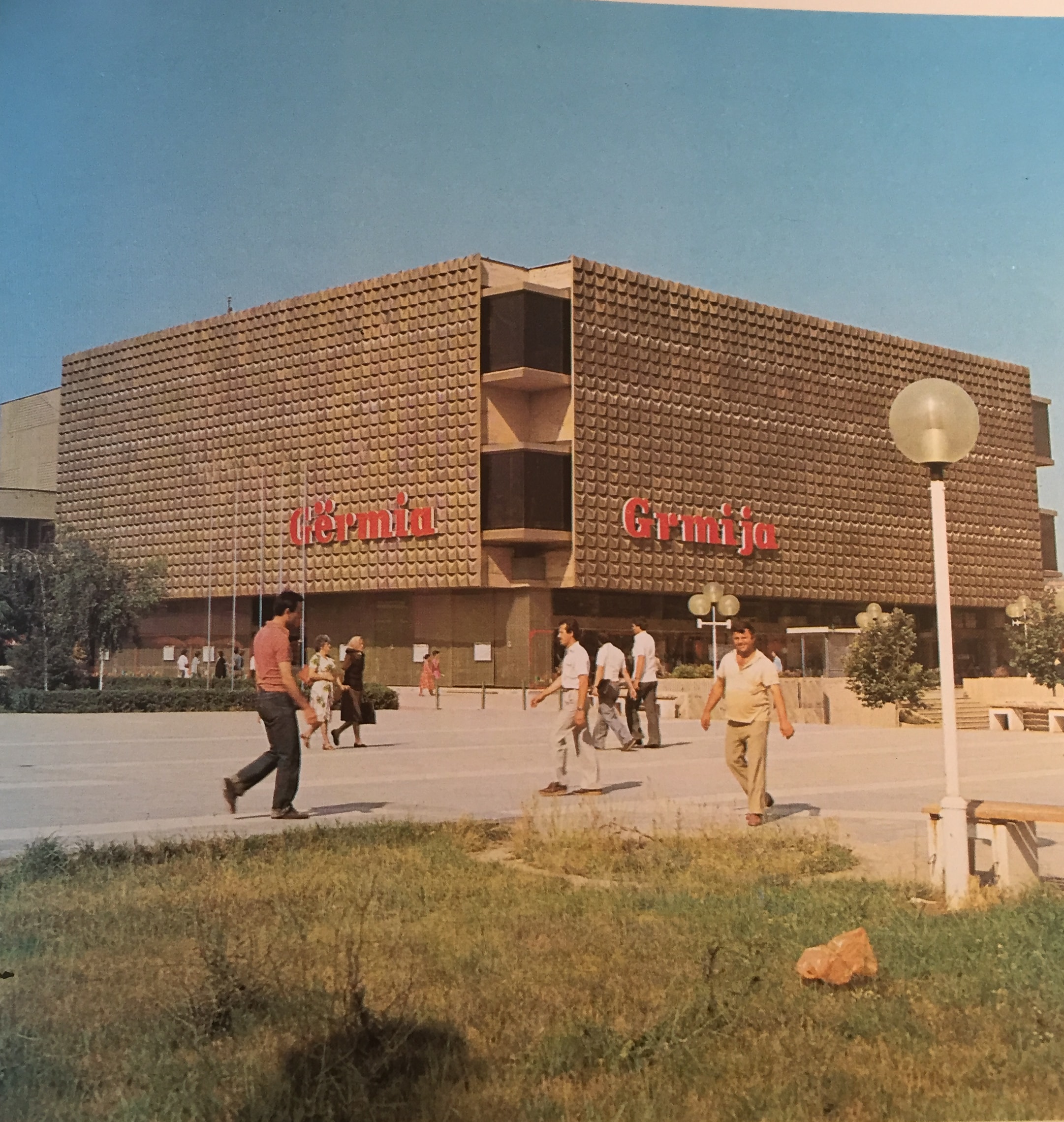

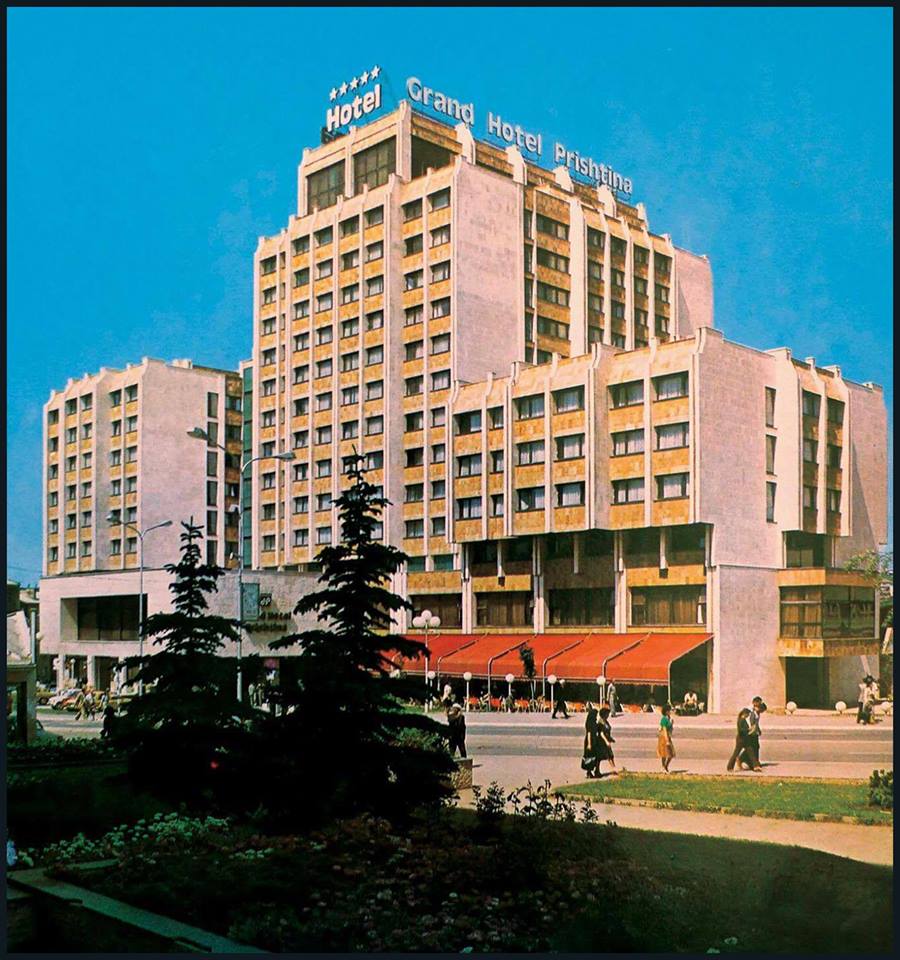

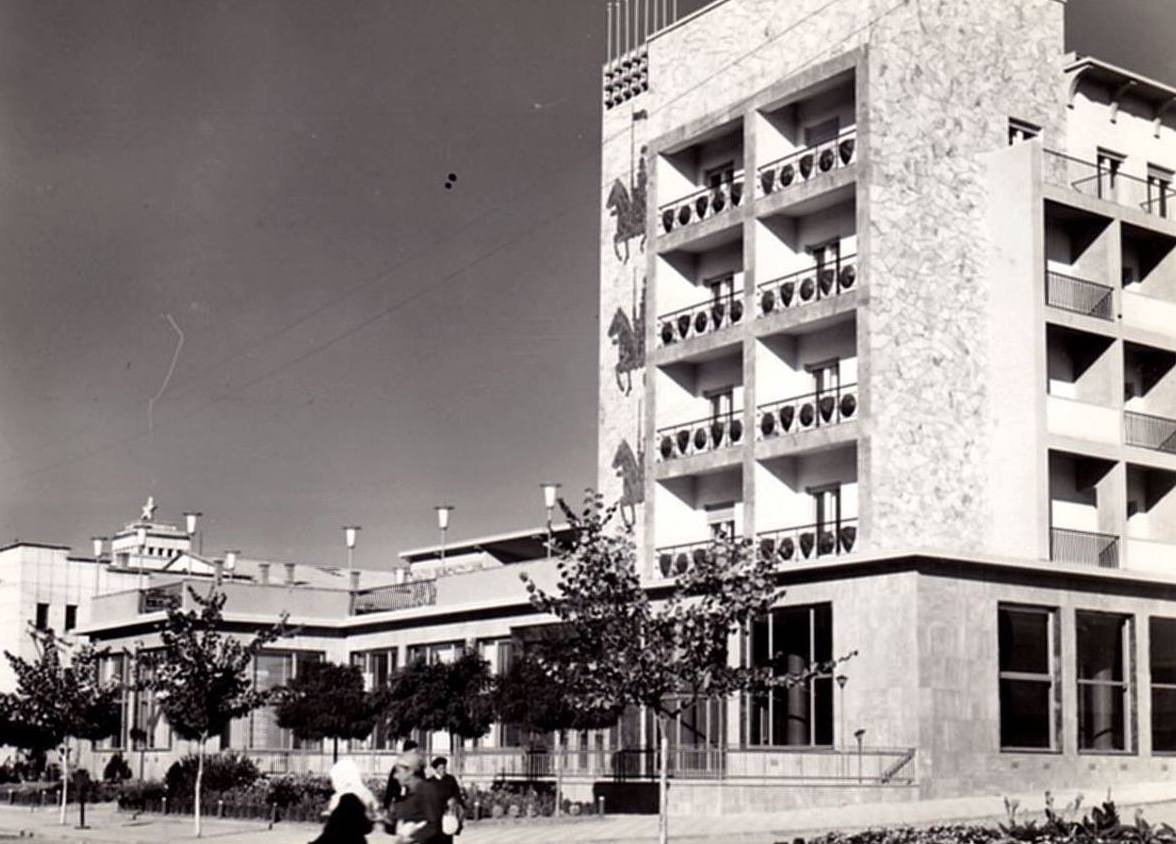

In the 1970s, asphalt was the epitome of progress. Pristina finally paved its much-despised mud roads. Tall buildings arrogantly replaced most of the old Ottoman dwellings and did away with that life for good. The 1974 Yugoslav Constitution made Kosovo an autonomous province, which called for large-scale development accompanied by new aesthetics of socialist modernism. Most institutions found homes in new buildings, all of which captured the latest architectural styles; concrete dominated the exteriors and expressed the ambitions of the working class, while marble furnished the interiors of the political cast. This visual compendium explores architectural vocabularies and traces the beginning of Pristina’s expansion after the Second World War.