Live, work and be fair and honest, honesty wins over everything. Earn the money with your sweat, not with lies. If someone hires you, go, take your pay, but do your work fairly, so they can come another time and hire you again. I have the case of a former secretary at the Utility Company, now she lives in Niš. Every year she would call me to go and mow her lawn in Prilužje. Aren’t there others that can do it? Yes. But she saw an honest person in me and she would only hire me. Price was never an issue. When she would ask me, ‘How much?’ I would tell her, ‘As much as you want to give me.’

Sinan Ramić

Agim Paçarizi

Political activistThere was a group of students from Podujeva who, it was said, had disarmed a police patrol. They were brought to [the prison in] Lipjan… One day, we saw that those students were also being brought out to walk. There was Jetish Rekaliu, who had been a teacher to some of the students who were now walking through the yard. We, from behind the prison bars and windows, started calling out to them by name, giving them moral support. Some of the students smiled back, some might’ve said something, I couldn’t hear it. Then one of the guards, an Albanian, lined [the other guards] up and said, ‘I’m going to give each of you a stick.’ He handed them each a baton. The teachers’ reaction, especially Jetish [Rekaliu]’s, was furious. He grabbed the prison bars and shouted at the guard: ‘You idiot! You lowlife! How dare you beat children in front of us?’

Lirije Osmani

LawyerIn the seventh grade, after the expulsion of Albanians to Turkey began…I had a deskmate, Nazmije, I don’t remember her last name. When the letter came that she absolutely had to go to Turkey, it was an extremely heavy event which left such an impression that I will never forget it. Every time I remember it, somehow I get very emotional. All the people of Mitrovica would go out to the train station. It was the Belgrade–Skopje train. Because there had also been an agreement with Skopje, that they should go to Skopje where they were given some kind of papers, permits called vesika. Then Turkey accepted them and… that atmosphere was so heavy, that all the people cried. Those who were leaving cried, their relatives cried, the people cried. No one knew what kind of fate was awaiting them…That experience with that classmate was very hard… We went to the train to see them off, the crying and screaming went on. It was very sad. I don’t have any nostalgia for Turkey because our people suffered. They never opened schools, they didn’t let them speak the language…

Mamudija Mustafa

All of us, Roma, Serbs and Albanians, are doing better now. One had hate for the other before the war, and also right after the war, but now it’s better. I do go out and spend time with people and I keep looking and I see people do better, Roma, Serbs and Albanians, we all are doing better…Because I think that no one wants another war, to go through that fear and destruction again. No one wants their child to have to go through what they had to go through the war.

Mehdi Skenderi

Roma music was everything! I always loved music. When I got married in 1995, during the peak of inflation, I had a huge wedding. I even wanted a helicopter, but couldn’t get it!… Yes, it was [one of the biggest weddings in the Pristina region]. I prepared two oxen and five sheep. We had everything: fish, barbecue, drinks. I even brought a brass band from Vranjska Banja in Serbia, 10 musicians! I paid them 100 German Marks upfront with help from my cousin Jashar, may he rest in peace. I loved music. I worked, saved, and did it properly… Definitely my wedding [is the most unforgettable memory].

Ridvan Gashi

Journalist“Before the war, there were good living conditions for the Roma in that mahalla, all the Roma were integrated. When I say they were integrated, I mean everyone was working, everyone had their own craft where they worked, there was some kind of order so to speak, where everyone knew what they were doing and where. They were not dependent on social aid, as it is now, they were organized politically, they were employed, and we had activism, political activism as well, Roma had their voice heard, in Kosovo Polje. Many Roma in Kosovo Polje worked for known companies such as the power plant company, the water company, the flower company — a company where before the war, from ‘90 till ‘99, over 500 families worked, now there is no one working there, because the modernization happened and everything went private.”

Ramadan Avdi

BlacksmithThere were a lot of those holidays, how to say, we used to celebrate Erdelezi and that for many days, we would go to each other’s house. It was not just to go to eat and drink, but the thing is that we stick with each other… We used to celebrate Vasi, and that as well was celebrated for 2-3 days… My late father would sing the bread, and then we would gather all together, the whole family would, and we had a lot of expenses… My father would sing the bread, and he would sing to everyone that would come, for every male, or kid, from every family, all… And all, because then people used to feel the impact of the singing… And then, let’s say, there were weddings, and then there were diverse festivities.

Aiman K. Zureikat

Military contractorI spent four years of my life in Kosovo, I travelled all over Kosovo, off-roaded all over Kosovo. I used to know Kosovo like the back of my hand, okay? It’s a beautiful country. I went all over, and the nice thing about it was that I felt more at ease and at home in Kosovo than I did in the other former Yugoslav countries because Kosovo Albanians had a lot of the same culture that I grew up with, yeah? […] [What happened in the war] was really sad because here’s the problem: in Kosovo, you had Christians and Muslims, okay? So, it wasn’t about religion, it was about ethnic cleansing.

Avni Mustafa

One morning, all of a sudden, you see four or five Albanians in our yard…they were friends with my father too, but the friendship disappeared, man, because they were in our yard with knives and things like that, trying to look for their things… I’m not saying that things didn’t disappear during the war, but…even though my father and my mom were saying, ‘We didn’t take anything from you guys, please, we’re friends’… what they saw was a trunk with these clothes from a wedding and …they saw that these clothes did not belong to them but to my mom, and I remember the moment when they were taking all the things outside, they were putting them on the ground, they didn’t care, and they left it like that…I will never, ever forget the scene that I saw after they left. I saw my mom sitting there, you know, making sure that everything was settled again, you know, as it was before, it was a nightmare.

Halim Hyseni

Education ExpertWe were in Podujeva. The schools were closed. […] Bajram and I went to visit them. The atmosphere was extremely heavy, the anxiety very great. I told them, the secondary schools were in question, I said, ‘Don’t worry, classes will continue in Albanian.’ That’s where the idea was born. Because at that time, I worked in the office of the Pedagogical Institute, where the Veterans’ Association is now, that’s where we had our offices. I worked until midnight, thinking what to do, how to do it. […] I knew there were around 10,000 police officers in Kosovo. I also knew that we had about 12,000 classes. There was no way to stop education when people wanted to be educated. Under those conditions, in the meadow, in the meadow; in the field, in the field; in the house, in the house.

Remzije Limani Januzi

Political activistThe demands were mainly political. ‘Self-determination!’ ‘Free the political prisoners, Adem Demaçi, Rexhep Mala!’ We called all the political prisoners by name, ‘Trepça works, Belgrade prospers!’ ‘Kosovo Republic!’… ‘Constitution, either through peace or war! […] Hydajet spoke, he spoke as a worker, with his hat on, he was wearing simple clothes, he was a worker and we didn’t know him at all. And that day, Teuta… that situation didn’t let you be passive. And I said, ‘Teuta, you climb up, climb up as a woman. Why should only men climb up? Let the women climb up too.’ ‘No, you climb up Remzije.’ I don’t know how it happened. ‘You climb up, you climb up!’ Before I did, my brother wrote those demands, what to say… on someone’s back, I think it was Teuta’s brother. And he gave me those notes and I was wearing a skirt, it wasn’t exactly easy for me, and then Hydajet Hyseni asked me, ‘Do you recognize me?’ […] And I called the slogans and the crowd was even louder because it’s a little different when a woman speaks. I came down and continued rallying until the evening, it was dark, very dark, it was late. They dispersed us with tear gas, we scattered and didn’t see each other anymore. I lost my shoes and I saw a guy running down the street, I don’t remember what street that was. And he gave me one of his shoes… I kept it until recently. I don’t know whether someone threw it out recently, because I wanted to keep it as a memory, a memory to keep in a museum — that shoe, to tell about where it happened, what they did, what we did at that time.

Xhafer Ismaili

Retired teacherSerbian students fought with Albanian students in Runik…They sent Vahide Hoxha, Fadil Hoxha’s wife, to take care of the incident…That woman was a lady, an incomparable woman. A woman like [Madeleine] Albright… There were communists there who, when something like that happened, liked to act holier than the Pope, acting like they cared so much about Serbs…We were stuck there for almost half the night. Then I spoke. I said, ‘What happened here often happens even among Albanians; they fight. It didn’t happen with any kind of agenda. It didn’t happen because they were Serbs and we were Albanians… We can try to give it whatever meaning we want, but it has no political color, no ethnic hatred, nothing.’ The meeting ended…There was still a café open, we went in for coffee and talked with Vahide. Vahide said, ‘You got us out of a crisis. Morning would’ve caught us there if you hadn’t spoken’… Avdyl Miftari, the history teacher, said, ‘Comrade Vahide, Xhafer wants to stay here all night because he has nowhere else to go, no apartment, no nothing.’ She looked at me and said, ‘You don’t have an apartment?’ I said, ‘No, I don’t.’ She said, ‘You’ll have one.’

Linda Gusia

SociologistWe used to throw little gatherings in the middle of the day, for example. At 12:00 we would draw the curtains shut and then… afterwards we went home to have lunch with our parents. That was the reality. We always had the feeling that we needed to live some kind of normal life, to create a sense of normality, and in that normality, a form of resistance. At the same time, our reality was extremely degrading and oppressive in every aspect of our lives. It’s very interesting how people adapt to inequalities of that scale. For example, everything was segregated. You had to be very careful about where you went to shop, which store you entered, what you did… everything had to be calculated. For someone who was 14 or 15 years old, everything was calculated, and the decisions you made were very important for your own well-being.

Sami Rama

School principal[The Trepça technical school] started the school year ‘94–‘95 in a private house in the Bajr neighborhood, and that’s when the police intervened…It was the 15th of December. It was a cold day, a day with thick fog, very thick fog. While coming to school, the students noticed the police circling around. That house had a yard surrounded by a wall, we came out and closed the gate… But they climbed the wall, entered the yard, and went straight into the classrooms… I remember that they mistreated me in front of the students…Whatever they found on the desks, they threw into the stove, those were iron stoves, and they burned it. They made the students write their symbols on the board. And then, at some point, they let them go. I was savagely mistreated in the hallway… They destroyed the classrooms, they even knocked over the stoves, stoves that were still lit. Before they let me go, they made me grab the lit stoves, I am telling the truth, until my hands were burned.

Bajram Shatri

Education expertThe first-grade class was sitting on the floor, learning the alphabet, writing their first letters on the floor. In Fushë Kosovë, for example, the situation was catastrophic. Those rooms would heat up quickly and get cold quickly. Then it would happen that to get to the classroom, one had to pass through the kitchen or hallway. The idea for home-schools was given by Halim Hyseni. I remember a journalist once told him, ‘What are you going to do there? They cook beans in that room,’ I’m simplifying here, ‘The meal is cooked there, students study there?’ Halim replied, ‘Then you tell me, where else should the students go to learn? Show me a place where food isn’t cooked and we’ll send them there.’

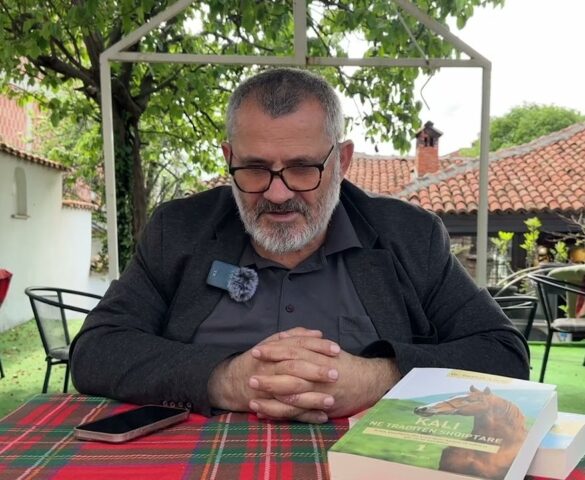

Nexhat Çoçaj

AnthropologistAt that time, the information office was in the premises of the mosque in Kruma, within the headquarters of the KLA. All those individuals who had either experienced rape by Serbian soldiers and police, or those family members who wanted to reunite with their families, came and presented themselves there, and we, as members of the KLA, helped the population to reunite. One case of particular interest in this regard was when Sadije Morina from Raushiq of Peja, whose child had died, didn’t want to leave it, even dead, to the police. On the other hand, she didn’t want her own family to find out that the child had died, and she kept the dead child for 24 hours, before reaching Durrës, giving him the bottle, and the bottle froze in his mouth, because when a person dies, they stiffen, and the bottle froze…When she crossed the border, the bottle, with the milk inside, was in the closed mouth of the dead child, and another woman approached [Sadije] at Qafa e Prushit, where the Albanian military forces, who were helping those crossing through the mountains, were located, and she said, “Is it possible for you to give me that milk so I can give it to my baby?” She replied, “No, it’s not possible because my child has died and I cannot take out the bottle.” I wrote the novella The Milk of Death based on this interviewed.