My family was deported in animal trucks to Albania, and they didn’t know what fate awaited them. They thought they were going to be killed and end up in a mass grave. My mom is a doctor, a medical doctor, and she said, ‘I just took my diploma, our IDs, your birth certificate, and some clothes for you.’ But she hid the diploma, the IDs, and some photos because she had seen films about Auschwitz, the Second World War, and the war in Bosnia. She said, ‘I knew they might try to say we don’t exist, that we have no identity. So I had to prove we existed.’ She took the risk of carrying the documents, even though people were burning IDs and papers near the Albanian border.

In Spring 2025, Anna Di Lellio taught Oral History at the Rochester Institute of Technology-Kosovo. The students enrolled in this class quickly discovered the opportunities that oral history provides. They learned how life narratives can illustrate the ways in which individual stories and broader historical events intersect and how the cultural identity that is present in those stories builds a community narrative. The interviews these young researchers collected make the recent history of Kosovo come alive through the multiple voices of war and its aftermath: the fighters, the commanders, the children of war, the civilian victims and leaders, the fixers, the internationals, and the humanitarians.

Elion Kollçaku

Aiman K. Zureikat

Military contractorI spent four years of my life in Kosovo, I travelled all over Kosovo, off-roaded all over Kosovo. I used to know Kosovo like the back of my hand, okay? It’s a beautiful country. I went all over, and the nice thing about it was that I felt more at ease and at home in Kosovo than I did in the other former Yugoslav countries because Kosovo Albanians had a lot of the same culture that I grew up with, yeah? […] [What happened in the war] was really sad because here’s the problem: in Kosovo, you had Christians and Muslims, okay? So, it wasn’t about religion, it was about ethnic cleansing.

Avni Mustafa

One morning, all of a sudden, you see four or five Albanians in our yard…they were friends with my father too, but the friendship disappeared, man, because they were in our yard with knives and things like that, trying to look for their things… I’m not saying that things didn’t disappear during the war, but…even though my father and my mom were saying, ‘We didn’t take anything from you guys, please, we’re friends’… what they saw was a trunk with these clothes from a wedding and …they saw that these clothes did not belong to them but to my mom, and I remember the moment when they were taking all the things outside, they were putting them on the ground, they didn’t care, and they left it like that…I will never, ever forget the scene that I saw after they left. I saw my mom sitting there, you know, making sure that everything was settled again, you know, as it was before, it was a nightmare.

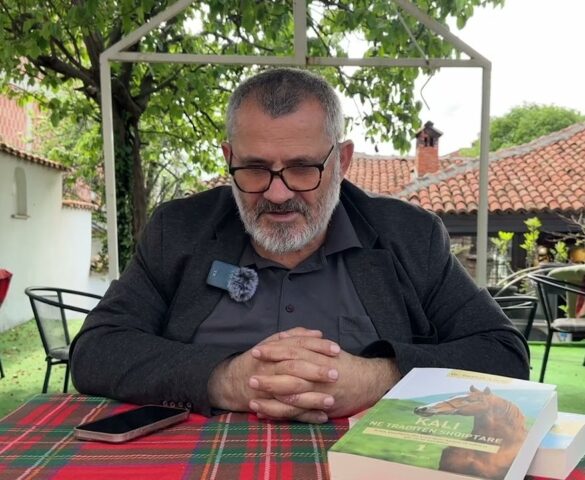

Nexhat Çoçaj

AnthropologistAt that time, the information office was in the premises of the mosque in Kruma, within the headquarters of the KLA. All those individuals who had either experienced rape by Serbian soldiers and police, or those family members who wanted to reunite with their families, came and presented themselves there, and we, as members of the KLA, helped the population to reunite. One case of particular interest in this regard was when Sadije Morina from Raushiq of Peja, whose child had died, didn’t want to leave it, even dead, to the police. On the other hand, she didn’t want her own family to find out that the child had died, and she kept the dead child for 24 hours, before reaching Durrës, giving him the bottle, and the bottle froze in his mouth, because when a person dies, they stiffen, and the bottle froze…When she crossed the border, the bottle, with the milk inside, was in the closed mouth of the dead child, and another woman approached [Sadije] at Qafa e Prushit, where the Albanian military forces, who were helping those crossing through the mountains, were located, and she said, “Is it possible for you to give me that milk so I can give it to my baby?” She replied, “No, it’s not possible because my child has died and I cannot take out the bottle.” I wrote the novella The Milk of Death based on this interviewed.

Agron Limani

Electrical engineerI thought that the civilian population should withdraw from the village, more precisely, I thought that the young people, who could be the target of Serbian forces, should be the first to leave. ..I went to the population in the valley where about 700 people were gathered…I appealed for young people to come with me, leave; some of those who were present but unfortunately are no longer among the living, said, ‘But we are civilians, unarmed, we are with women, with children, with pregnant women, with young brides, with babies, why would we be a target of Serbian forces, when we do not pose any risk to anyone?’ I answered, ‘Because you need to understand the fact that Serbs have traditionally attacked the civilian population, Serbs have traditionally attacked unarmed and defenseless people, so I think it is better if we leave.’ …After a couple of weeks, we heard the first news …through a small transistor radio… that over 100 Albanians had been killed in Krusha e Vogël.