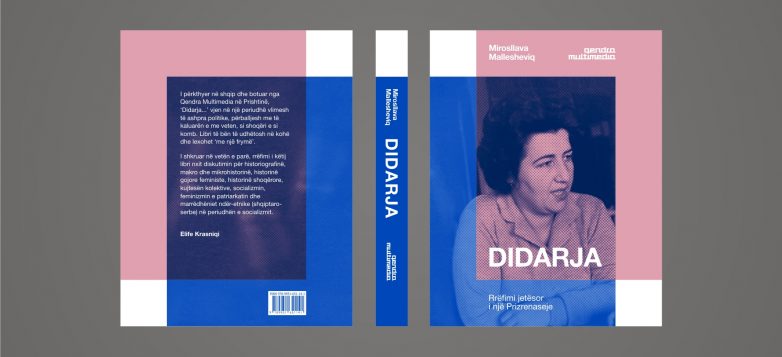

Excerpts from Miroslava Malešević, Didarja. Rrëfimi jetësor i një Prizrenaseje (Didara. The Life Story of a Woman from Prizren) [Translation by Shkëlzen Maliqi], Qendra Multimedia, Prishtinë, 2016.

www.qendra.org / [email protected]

First Published in Serbian as, Didara. Životna priča jedne Prizrenke, Etnološka biblioteka, Knjiga 14, Beograd 2004.

[…]

FEREXHJA[1]

After fifth grade, before I turned twelve, the time came for me to «mature» as a girl. According to the Islamic custom, when a girl has her first menstruation, this is the sign that she has grown up and cannot go out in public without the ferexhe [from now on veil]. At the same time, for me it meant the end of school. I experienced this as something that was understood, because it never crossed my mind that life could be different, because something different simply did not exist. Nor did dad insist, it was wartime. However, after the end of fifth grade, I said farewell to further education without any regrets. Now, my mother had made a veil for me and everything was ready to announce the new status I wanted: the community with the other covered girls, weddings, parties, and the preparation of the dowry for the wedding. I strongly desired to become a grown up girl and that the others looked at me that way. In Prizren the custom was that this change from child to girl was made official through a ritual. When the moment came, my mother folded some clothes and the veil in a bag and explained what I needed to do and where I should go. The ceremony consisted of a last walk through the city, to visit alone all the places where I had been as a child, in order to bid farewell to those streets and places. It was one of my last appearances before the world with my face uncovered, because I would never return unveiled to those places, as I did when I was a child. So, the walk was a farewell to my childhood. This whole story now seems very sad and upsetting, but then, I remember very well, I did not mourn because my childhood was officially over. Rather, I was happy for having grown up. After that stroll, as foreseen by the “protocol,” I went to my maternal aunt as a guest. There, they were waiting for me, everything had been arranged in advance, it was part of the ritual. My aunt had two older daughters, already prepared for marriage, and I was their guest for a few days: they entertained me, they introduced me to their friends, which meant that they accepted me into their circle, that I should feel equal to them, that I had become an adult girl. After a few days passed, and during this time I did not dare leave my aunt’s house, again, according to customs, my aunt gave me gifts that she had prepared for me and put the veil on me. I returned home in my new role. From that moment on, as a woman, I would never appear in public with an unveiled face.

All veils were sewn in the same way and in the same color, black, but distinguished by the quality of the material that is worn by young girls, which is different from that of married women and those older. New brides, for example, wore a silk veil. All veils had two parts: the skirt part was long, as to cover the lower body, which was then tied with an elastic band at the waist; and the upper part was closed completely, you wore it head first, and it had long sleeves. Veils were sewn very large, so underneath you could even wear a coat. Over the face there was a transparent fabric, peqja.

In the streets one walked completely covered, but when we went somewhere as guests, in confined spaces and among women, the veil was removed. Should you go in for short visits, only the part that covered the head was removed. In our homes we did not keep the veil, because women were not covered before relatives. For this reason, in every home there were signs that announced known visitors: for example, if there were two knocks on the door, we knew that our maternal or paternal uncle was coming, and we opened the gate freely. If that were not the sign, we would ask, “Who is it?” Let’s say, for the mailman we extended only our hand, we did not show our face.

Granted, seen just from the outside, especially the part that covered the head, the veil might leave non-informed viewers with the impression that all women are wearing the same uniform without an identity. Wealth, luxury, imagination, taste, all this surfaced when women removed the veil. And to all these things we devoted great attention. My mother bought me the best clothes, I always sewed something, for every occasion I had a new dress. At the same time, I was also provided with qeiz[2], the dowry for my wedding: towels, sheets, tablecloths, lace, everything that I would need for my future family. This was the most important thing to prepare before marriage. On the occasion of the wedding, it was customary to expose to the public all the qeiz. All parts of the dowry were exposed all day, anyone who wished could see them, just as in an exhibition, therefore the girls, and especially their mothers, tried to have the dowry as representative as possible. Girls copied embroidery from each other, some jealously hid innovative things to impress everybody at the right moment, etc.

The rreth[3] in which I lived in the early years of my adolescence was very limited, but another simply did not exist, so my world at that time did not seem so small. I spent my free time mostly with friends and making handicrafts. During visits, it was especially important to learn how to dress and get all dolled up with friends. We embroidered a lot, it was lovely to prepare many things for the wedding, we never knew when our true nafaka[4] would come, one cannot marry unprepared, so I and the other girls were helped in the preparation of the dowry by our mothers, grandmothers and aunts. At that time, I started to learn how to cook well from my mother, but I did not like it that much, and in this regard, I never managed to come near my mother’s artistry.

The largest celebrations were weddings, especially kanagjeqet[5], maiden nights, in which a wide circle of girls gathered. In the Kanagjegji, organized before the wedding ritual, the entire body of the future bride was waxed and painted with henna [kana/këna] (from which the name kënagjeq – the night of këna – comes). After the ritual, the bride appeared before the guests, who were served tea and cakes. She changed clothes several times during the evening, showed the most beautiful dresses, then she wore the wedding dress and her behavior exhibited all the proper manners of a future bride. Thus, those who were next in line to marry were taught certain rules. But these were events where also the other girls showed-off their beautiful looks. In these gatherings, older women watch carefully how the girls are dressed, what jewelry they wear, how beautiful they are, how elegant, what manners they have. This was virtually the selection of future brides: if you drew the attention of the sister, the paternal aunt, the maternal aunt, the wife of the maternal uncle, etc., of some man looking for a bride, you had a better chance of getting married.

That was my whole world, no other outlet, no travel, books, male friendship, nothing. The whole period of the war for me passed with this kind of adolescence, in the close circle of my peers.

[…]

A DRAMATIC TURN

They had convinced my father, these Party people, that the time of a general emancipation was coming, and it has remained unclear whether this was the reason why that old desire that I went to school returned, or he feared the new government and decided from conformism to keep pace with the times. But in my life there was an unimaginable turn. In 1947, the Party directive had come to convince the most influential people in the city of the necessity for veiled women to remove the veil. By their example, then their families’ example, these influential people should show the path to be followed in the new society. My father had been at the first meeting of this kind and decided immediately: his daughter would remove her veil. Granted, I was not asked at all.

He consulted with Enver[6], who immediately agreed and he began to “re-educate” me. I experienced my father’s decision as a terrible punishment. When he announced to me that he had given his word to the local Party Committee, I was shocked, amazed, without the power to object, to ask anything. I cried all night. I could not imagine a more terrible situation than the one to which my dad had pushed me. I was seventeen years old, I wanted to marry, not be different from my peers. I saw before me the unlucky Sadijë, the late daughter of my paternal aunt, and I feared that I would find her destiny too. She at least had chosen her own way; I had been taken to that road without my will. I felt miserable and powerless; my father’s decision to lift the veil condemned me to walk the streets naked, as if to force me to prostitute myself. I thought I could not survive this disgrace.

And then a new shock came. That year in Prizren, perhaps a decision linked to the campaign on the veil, they organized teachers training for Albanians. The course, which lasted three months, had to increase the number of Albanian cadres working in primary schools, because a campaign to teach literacy to the population had begun. My father decided that I had to attend the teachers training. Everything was against my will and came so quickly. Nobody asked my mother or me anything, but she thought, reasonably: “If you stay home, I don’t know whether you can marry. If you have your salary, perhaps you will find it easier in any case,” she said. And indeed, that course soon showed that it was my only chance not so much to marry, but for my life to take such direction. I went, also because I had no choice.

In the class there were forty boys and only three girls. I went to classes always wearing a dress with long sleeves, and up to my neck, though it was summer and from shame I did not dare look or greet people on the street; they did not greet me either. When I was on the street, they said all kinds of things, the women came to see me, they said to each other, “Come to see the daughter of Gani Tada, she walks without the veil!” The earth opened under my feet from shame! That first day of school, Enver had brought home two other girls from the class to get to know each other and go to school together, because I did not dare walk “naked” alone to school. Near the school there was a boarding school where all trainees coming from other countries of the Region were staying. They went to three courses, a low, middle, and high level. With me, in the low level, there was only one other girl.

[…]

A NEW TURN: MEETING WITH TODOR GJORGJEVIC

In our house there was also a hostel, and there were always many guests. I no longer helped in the reception; I had my work and my salary. There were mainly some Party workers. I almost never saw them, but I noticed one of them, however, because he came quite often. He was this Toša Gjorgjević, the secretary of the Party Committee in Dragash. He often went to meetings in Pristina. Prizren was a bus journey from there. When returning from Pristina, he came around to sleep the night in Prizren. Often we met at the house, but did not communicate. I thought he was handsome, I had noticed this, and found that he also looked at me me and liked me, but I didn’t think more than that. We belonged to different worlds, I would not dare do anything more than those little exchanges of looks from the corner of the eyes. To my luck, he dared. One day he stopped me in the city; he introduced himself and expressed the desire to walk me home. I accepted. I walked in broad daylight in the center of town with a boy who was not Albanian and I was fully aware of the risks, but I liked to be with him. I considered that a teacher could afford to walk with a guy, at least as a companion, and that others would understand it this way. But these walks of ours, after the first one, intensified, because he stood casually, whenever I finished teaching, and always walked me to the house, before the eyes of everyone. Only that the way home became more and more indirect, because it was important to us that we spent more time walking together. This was the only way to be together longer and not look suspicious. I enjoyed his company, I waited for him to appear, but I did not have the courage to admit that I was in love. In fact, I did not know that I was in love, because a relationship with a man of another religion or nationality seemed completely unfeasible, as well as prohibited, so I dared not even dream of such a thing. I enjoyed just that what I had, social conversations and walking together for kilometers. One day he ran into me again “casually” in the city center and without missing a beat he told me that he liked me very much, that he came so often to Prizren for me, in short, he told me that he loved me. I was confused, I was amazed, I was scared – all at once – I did not know what to say. He said that he was determined to try all or nothing. He told me all about himself, what he worked on, what he had, all the details, and finally he told me that he wanted me as a wife, he wanted to marry me, and asked me to think about the proposal. Communist from head to toe, Toša was not impressed at all by our different national origins. He lived in harmony with his beliefs and sincerely believed that the prejudices of this kind were gone forever in the new times. So, he was not interested in what my parents would say. And I did not know what to say about this. Refuse? I did not know how to do this, since I liked him more and more. Tell my dad? He would kill me or he would die of shame! My decision was influenced by another boy. At the same time there was also an Albanian from Prizren who hung out outside the school, waiting for me, he said that he liked me and that he would come to my house to ask for my hand. I did not like this guy at all. I did not want anything to do with him. My refusal was especially reinforced by his aggressiveness, he wanted to touch me, he tried to embrace me, perhaps thinking that the free girls of today must not be asked to allow these intimacies. Unlike this guy, Toša was more restrained, showed great respect. I definitely and totally cleared the accounts on this guy in my head when on one occasion he told me that he would not allow his future wife to be employed. With this, he touched me in my pride. After all that had I had gone through, he wanted me to become a traditional woman under his shadow! To go back to such role was out of the question. Toša spoke differently and I trusted him. But the city of Prizren was observing all, it had registered my walks with Toša, and gossip about this had reached this boy and my mother. My mother was easily convinced that there was nothing with Toša, it was simply slander, while to this guy things seemed much clearer. Therefore he rushed, although I openly said that I did not want to marry him, to send a mediator to make a formal request to my father.

My mother told me that she and my father had decided to give their consent because they thought that the boy was fine, from a good family, that I would be well off, and so on. I cry, and kindly ask to persuade my father to change his mind, I tell her that I do not like that guy, I do not want to get married, but all this makes no impression. My mother does not understand. But even if she understood – she does not dare express it. She simply says, “Do you think that I loved your dad when I married him? And, behold, we are living in a good marriage for nearly thirty years.” I went almost crazy. I did not want a “good” marriage by contract like hers, I dreamed of romantic love.

My parents had a week, as was the custom, to give their definitive answer. This meant that in one week, when dad gave the answer to the mediator, I would become the property of that boy, he would dispose of my life, he would decide for me as his property. Should I go back fifty years? At that time I was taken with the idea that I was a pioneer of emancipatory change among the women of Prizren, and now I could not let them marry me against my will. I waited for Toša at the place where we had decided to meet and told him what was being prepared as my fate. We had just started to date, respectively, I had just begun to think about his offer of marriage, I was forced to take a final decision and I put this condition to Toša, “My answer is yes, but it’s valid until Monday. If you wish to marry me, you should do something urgently. If my father gives his word to the other boy, then we cannot do anything. Never again will you see me. “I shouted, “Help! Save me! “Even he was surprised, but had firmly decided that we could not waste me. It was absolutely clear that we could not wait for the word of my engagement. We knew, so now it made no sense for him to come to my father to ask for my hand, he would not get the consent. In Prizren, there were no mixed marriages by rule, and not between two different nationalities, so this would be the first reason why my father would not consent. Even if he were Albanian, the top political position Toša covered without a satisfactory “pedigree” would not “fill the eye” of my father. Then, I had been formally asked in marriage by a “good case” (“and ours, and from a good family”) and that to my parents still looked better than an offer from a “nobody” from Dragash. Therefore Toša and I agreed that we had no choice but to escape before the fatal day. And I had made up my mind, the decision was taken. I trusted him; I knew he would not disappoint me.

ELOPING

Toša organized my “grabitjen[7].” He had first informed the [Communist Party] Secretary of the District that I was voluntarily joining him and had asked him to inform my father that I had left and where we lived. The District secretary, Maksut Skenderi, was a good friend of Toša. On Saturday night, two days before the deadline that my parents had given to consent to the engagement with the other boy, as directed by Toša, I had come to meet with Maksut, who had assumed the role of “link.” I had told my mother that I was going to school for a meeting. To not create suspicion, I took nothing. I calculated that the whole drama would end after a few days; Dad would be angry a little, but after that, I was his pet, he would forgive me. I hoped that he would be visiting soon and would agree. No deeper thought. To be honest, had I not been just nineteen years old and with a rope around my neck, I don’t believe that I could have made such a radical decision.

With Maksut I went to the exit of the city, where a driver and Toša waited in a truck. He had gotten the truck from the director of the transport company on the grounds that he had to take soldiers, border guards, from Dragash to Prizren. He could not find any other transport at the time, it was Saturday evening. And Toša had barely provided transportation for himself from Dragash, because the route-lines were irregular. However, I came to the designated place for the meeting and saw that the driver of the truck was a neighbor of ours. I did not want in any way to sit beside him in the cabin, he would recognize me. And Toša and I sat on the back of the truck under the oilcloth cover, but Maksut sat in the front, in the cabin, with the driver.

In Dragash, after several hours of tension, the locals welcomed us with celebration and shots, all had been notified, the Secretary of the Committee celebrated the marriage. Only when I got off the truck, the driver understood whom he had brought and for what reason. He thought that he had taken some important political personality with a secret task. How could he have otherwise known the identity of the person under the tarp, who travelled in a special truck to Dragash at night, accompanied by the Secretary of the Committee? “What have you done, Didara?” He was frankly shocked when he recognized me.

In the meantime the messenger sent by Maksut gave my family the news that I had left. This man told us later that he had barely gathered strength to get into the house and look at my father in the eyes, it felt as though he had committed some sin. There, he, along with my mom and my dad, had experienced a terrible drama. My mother had lost consciousness; my father was left speechless from the shock. During the evening the news spread across the city, relatives had begun to come to check whether the news was true, people had gathered in the house of my parents as if to give condolences. The pet daughter of Gani Tada has gone, and with a Serb! She has violated his word! My father could not forgive me this shame. That night he announced that I was dead in his house and forbade everybody to ever mention my name. For my family that evening I had ceased to exist.

[…]

ON THE NATION, LANGUAGE AND IDENTITY

I did not give up my national affiliation because of a mixed marriage, but with time I was strongly determined to become Yugoslav. I experienced myself as a Yugo-Albanian. Just so, the one and the other as an equal mixture. Of course, it was life with Toša that mostly contributed to this equal mixture, especially when the children were born. If you did not live in a mixed marriage, probably you could be called “Albanian among Yugoslavs.” So, with him and the children I felt equal in every aspect as an Albanian, and a Yugoslav as well. My children, for example, learned Serbian (at that time it was called Serbo-Croatian), at home we spoke Serbian, and this did not jeopardize me in anyway. With Toša from the beginning we spoke only Serbian, and later also with his family, because they did not know Albanian. In his family they communicated also in Vlach. I had heard for the first time this language, unknown to me, from his mother. Until then I did not even know it existed. Toša, however, did not know Vlach, I suppose because he lived in the company of Serbian children and spent very little time at home. Goran[8] learned many songs in that language as a small child from Dada [grandmother],, as I had taught him some Albanian songs, but he spoke none of these languages. He learned Turkish well enough as a child living in Prizren, while Suzana[9] learned Turkish properly during her studies, but I did not ask her to do that. My parents in Prizren even less. All spoke three languages fluently and never asked any question about it, automatically we switched to Serbian when we came to visit because of the children and Toša. For me it was important to constantly practice Serbo-Croatian, mostly because of education, in order to learn the literary language. The calculation was that I could not forget Albanian, let them learn at least good Serbian.

We both felt that the education of our children should be in Serbo-Croatian, due to greater opportunities in their future life. Perhaps I made a mistake in not teaching them the Albanian language, at least by not speaking to them in that tongue. Many friends have made remarks about it, probably rightly, but I simply did not do it. There are many reasons for this. Perhaps the most important is that I grew up between two different languages, Albanian and Turkish, which in my parents’ house had a completely equal status, so I also thought in both languages since my youth. I have not built, like most other people, a sense of connection to only one language. Bilingualism has been the first feature of my personal identity since the beginning, and I also easily accepted the third language, Serbian, since childhood, which it is not common for most people. For this reason I did not insist on the use of the Albanian language in communicating with my children, believing that they would be taught, growing up, all three languages. My children have passive knowledge of the Albanian language, but never spoke it. And if they knew a little from childhood, later the failed to revive the practice. The essence was that they were not forced [emphasis of the writer] to learn. They associated equally with all children, but had no reason to bother to learn another language, for all Albanian children (also Turks and Roma), especially in cities, knew Serbian. Despite language equality under the Constitution, the Serbian language was dominant in the Region while they were growing up. Documents, signs, traffic signs, all were truly bilingual, but in everyday communication it was considered normal for Serbs and Albanians to communicate among themselves in Serbian, namely for Serbs it was not necessary to speak Albanian. Most understood it, but didn’t use it. My husband also knew Albanian, but didn’t speak it, although he allegedly knew a “katundar[10]” version of Albanian, a non-literary Albanian, which he had learned as a child. For example, until the mid-sixties (before discharging Ranković[11], even after that) Albanian children (with Turks and other nationalities) were required to learn Serbo-Croatian, while the Serbian and Montenegrin children did not learn Albanian. Then the directive came that the Albanian language be introduced in Serbian classes, which was received with great displeasure. Parents protested in meetings with education authorities and then they made the compromise solution that Serbian and Albanian become optional subjects. I remember that at that time my Goran was in high school and once I asked him how did his learning Albanian go, did he need any help, the intention was that at least he would learn a little bit, but he told me that from the beginning no one in the class had been interested in listening to the Albanian teacher, so he did not teach during these classes. At first he had tried to speak louder than the noise of the students, but he had given up, so that the student of the Serbian classes used the period of Albanian instructions to prepare for the following hours, while the teacher during that time only read newspapers. Probably the same thing happened with Serbian as an optional subject in Albanian classes.

This would later lead to big problems. By the late sixties, the situation changed fundamentally. Firstly, Kosovo won wide political autonomy (especially since the amendment to the 1974 Constitution). The state began to invest huge funds in the economic development of the [Autonomous Kosovo] Province, as well as education, culture etc. The University of Pristina was established and the number of Albanians who earned a law degree and taught in their mother tongue increased. Boarding schools opened, which was of particular importance for the education of girls from villages. In previous times boys were allowed to go to the city for schooling, with girls it happened very rarely. And now many girls had the opportunity to run away from home to study, because they found accommodation in student dormitories. This was important not only because of the increasing number of girls with university diploma, but also to alleviate another problem that for years had stoked tensions in Kosovo relations. This is the “problem” of the high birth rate of Albanians, which in different circumstances was presented as a serious social and political problem and negatively affected interethnic relations. The fact that now these girls were studying had consequently extended their reproductive period, they started it later, after they turned twenty-four or twenty-five years, and not as fifteen or sixteen years old, as was the norm in villages. In addition, girls with a university degree intended to work and this circumstance also reduced the possibility that they gave birth to more children. So one of the most effective ways to reduce the [Albanian] birth rate was free boarding for girl students who came from villages.

With time, the number of jobs and the number of Albanians in leadership positions increased. To meet the national proportional representation quota in employment, Albanians had now priority in employment. For the first time, knowledge of the two languages appeared as a requirement to compete for jobs, and in the majority of cases, Serbs and Montenegrins could not fulfill this requirement, and this increased their unhappiness. Albanians very quickly became dominant in Kosovo’s political life. The Albanian language very quickly became the dominant language in public communication, and the growth of Albanian nationalism was apparent. Suddenly Albanians refused to speak Serbian (for example at service windows in offices, public meetings and the like), for which Serbs and Montenegrins began to feel vulnerable. Naturally, these processes did not occur just because of nationalist reasons. Let me give one example of how this took place in everyday practice: one day I went to my brother’s ambulatory to treat a tooth. I had not booked the appointment, calculating that he would take me in, as I was his sister-in-law. However, somewhere around ten people were waiting outside his door, and he apologized that he could not accept me, but asked his colleague, because nobody was waiting in front of his door. I asked, “Are you better as a dentist, or your colleague works more leisurely than you and you have more patients?” Ymer laughed. The reason is, he said, that his colleague did not know Albanian and the patients are mostly Albanians. Most of them are from villages, they do not know Serbian well. Well, this dentist did not relate to most patients, and people want to talk with their doctor, to explain what trouble they have, create mutual trust. So the most important thing, mutual trust, was missing, and this is due to ignorance of the language. People went to the doctor they could trust. There were also some who refused to address the Serbian doctor simply as form of protest, because they could do so. The result was, as in the case of Ymer, that the dentists who spoke two languages were overburdened with work because patients of all “colors” and affiliations went to them, while the others waited for any patient at all. This was the trend during the seventies. Many Serbs could not accept the change of status, or the loss of early privileges when it was implied that in groups one should speak only Serbian. This situation, which one party regarded as normal until the sixties, the other party obviously did not see as something normal. Most Albanians experienced the lack of will to respect their first neighbors by knowing their language, even symbolically, as a demonstration of Serbian superiority and rule, and this was now back as a boomerang in the form of Albanian nationalism. For example, an associate of Toša, and a good friend of ours, once openly told me that he is happy that he has Toša as a director, “because he would not bear that his boss was an Albanian.” “Oh well, you know what nationality I am, how can you tell me such thing?” I told him. “No, Didara, it is not the same, because you are something else,” he replied. I really was something else, but not in the sense that our friend thought. I was “something else” for both sides. However, I must admit that I did not think enough about these sensitive issues at that time. Obviously, I didn’t suffer enough. I passed from one language to another without difficulty, as it was needed, without being offended that most did not do so. I did not give importance to mockery when I made some mistake in Serbian. I considered these mockeries lack of personal culture and was not touched by them, just as I was not touched when some Albanian mocked me because I had “alienated” my children.

Regarding my children, I thought that it would be enough to learn that what [emphasis of the writer] a man says is more important than the language he speaks. This has been my personal goal and is common to my family. And it has also become the main feature of my life and my children. My Suzana now lives in Paris and of course is mostly French speaking. For a long time Goran lived between Belgrade and New York, therefore he mostly speaks English. However, both feel that Serbian is their mother tongue, although they are not native speakers. When some American friends asked whether Serbian is his mother tongue, Goran replied: “Unfortunately, I don’t speak either my mother’s or my father’s native language, but I can speak the mother tongue of my daughter” – an excellent answer, because Maša, his wife, is Serbian. I personally do not feel offended because Serbian was the only language in which I communicated with my children and never felt threatened because they did not know Albanian. It was important to understand each other, no matter which language we use. Frankly, today I feel bad because I lost the chance for my kids and myself to learn a world language, but not because I have not taught them their mother tongue. My family in the meantime got bigger, international, new members have come who do not speak the languages of this region and communicating with them is somewhat difficult, since the rule, “speak Serbian to understand the whole world” does not apply to them, although somehow we manage to understand each other. When you have goodwill, you find a way to understand. You must hear that Esperanto when the whole family gathers here. With Suzana’s husband, Stephen, who is French of Jewish descent, the family communicates mostly in English. With Noam, our little grandson, we speak French. Both speak a little Serbian, so it is necessary to agree on the basics, although someone must always come to help us with translation, so that Toša and I don’t feel left out. Sometimes, Suzana and Goran like to talk to me in Turkish, it is an opportunity to refresh their knowledge of Turkish, and when all this is mixed, all languages and translations, it is as if we were in an international meeting, and not at a family lunch. I simply relish this diversity of languages.

[1] Ferexhja/Ferexhe – a veil concealing the whole face except the eyes, worn by Muslim women in public.

[2] Clothes and embroideries that fill up the bride’s trousseau.

[3] Rreth (circle) is the social circle, it includes not only the family but also the people with whom an individual is in contact. The opinion of the rreth is crucial in defining one’s reputation.

[4] Nafaka – Luck or fate. In this context, it is the future husband and the term has a wishful tone, implying that one should be so lucky to meet her husband and must be prepared for her fate.

[5] Plural of Kanagjegj, Henna Night, a bridal shower, the ceremony held one day before the wedding that generally takes place in the home of the bride and among women.

[6] Didara’s older brother, a partisan who served five years in the gulag of Goli Otok after the war.

[7] Grabitje – forcible seizure, plunder. In this context the term refers to the kidnapping of the bride, as it was and sometime is still customary in some traditional societies.

[8] Didara’s oldest son.

[9] Didara’s daughter.

[10] Villager/Redneck.

[11] Aleksandar Ranković (1909-1983) was a Serb partisan hero who became Yugoslavia’s Minister of the Interior and head of the Military Intelligence after the war. He was a hardliner who established a regime of terror in Kosovo, which he considered a security threat to Yugoslavia, from 1945 until 1966, when he was ousted from the Communist Party and exiled to his private estate in Dubrovnik until his death in 1983.