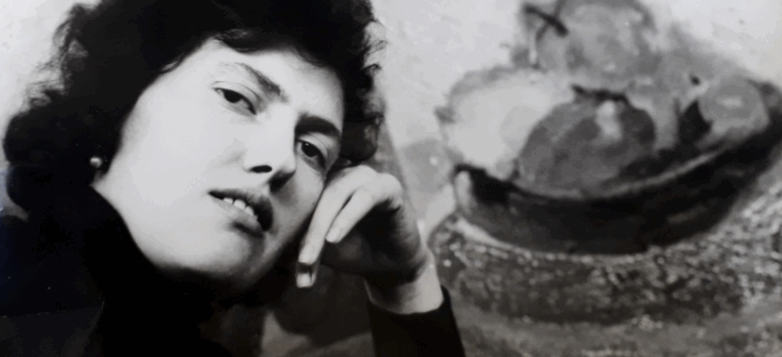

Jeta Rexha: Ms. Alije, can you tell us something about your early childhood, where you finished elementary school, what are your most beautiful memories?

Alije Vokshi: Yes, I finished elementary school in Ferizaj since my father had to move with work to Prizren, Gjilan… because he worked in the court. And I went to the elementary school there until the third grade, then we moved here, to Pristina, and here I continued at the Emin Duraku elementary school. Then at the Elena Gjika elementary school.

Jeta Rexha: How did the desire, how did the desire for painting come about?

Alije Vokshi: It started at the elementary school here in Emin Duraku, that is when, from elementary school, and it continued.

Jeta Rexha: Then you continued in high school, where?

Alije Vokshi: I finished middle school in gymnasium.

Jeta Rexha: In Sami Frashëri?

Alije Vokshi: In…

Donjeta Berisha: Back then it was called Ivo Lola.

Alije Vokshi: It was Ivo Lola.

Jeta Rexha: And after middle school you continued with your studies, right?

Alije Vokshi: Yes. No, first I went to the Shkolla e Lartë Pedagogjike for two years. Then my professor saw that I was working so well, he was from Montenegro, he told me, “You should definitely go to Belgrade to continue your studies because you are working so well, your portraits…” and I went to Belgrade. When I went to Belgrade for the exam… we worked for one week with colors, drawing, with… and in the end, I passed the exam, it was a big joy for me. All the professors came to me and asked, “But your paintings…” One of them was a painting professor there, she asked me, “You have something very special, keep it, you are working very well.” Another professor from Belgrade, Zoran Petrović, complimented my portraits, so they really motivated me and I was very happy when I passed the exam, it was a big joy for me.

Donjeta Berisha: Was it difficult to enroll?

Alije Vokshi: Now, I don’t want to say that it was, but I know that when I saw myself there, my name… auu {onomatopoeic} … such joy.

Donjeta Berisha: Did you have problems going to study abroad, considering that girls at that time weren’t that free to study?

Alije Vokshi: I wasn’t even thinking about going to Belgrade, but my professor, he was the reason why I went.

Donjeta Berisha: How did your family react to it?

Alije Vokshi: No, my family, my mother said, “There is no way you are going there, you have to stay here and get married, look around all your friends are married already,” but my father allowed me, he said, “You have to go and that’s it!” And so, I did five years there. Two years here, three there, five in total.

Jeta Rexha: How do you remember your student life there?

Alije Vokshi: In the beginning, I had no credits nor scholarship… it was a little difficult. My father always worked, we were four children. He didn’t know what to do with the money, educate us or… the salaries, income back then were very low. I had difficulties in the beginning, but then after taking the scholarship and credits, then I had a really good time. I would buy canvas and colors, I would buy cloth, I would buy everything. That helped me a lot, my professor was, the other professor when I was in the third grade, in the third year in the class of professor Milo Milunović, he was from Montenegro and he studied with [Augusto] Giacometti, he only wanted us to paint landscapes, and I didn’t know that nobody dared to interfere in his subject… I didn’t know.

And we would take the bus to go to the city center from the city of students, and in the center of Belgrade there was Hotel Moscow, and there I saw a Roma, a Roma, you know a magjupe, how to say, dressed in their… I liked them a lot because they looked very special and I asked, “Would you like to come?” We had to go by bus Topčider, to change buses from one to another; I took her, she accepted. And I sent her there, my friend said, “What have you done” she said, “Don’t you know that the professor doesn’t want anyone to interfere in his work, in his syllabus, he only wants us to do still life.”

Ku-ku, but in the end when everybody finished their portraits, he was really pleased. And so, he gave me an excellent grade; there were people coming from Tuzla there, from Tuzla in Bosnia, there was Nezir Čorbić, and the professor loved him. My roommates were there and when they heard that I got an excellent grade they were like, Imagine, Alije Vokshi has received an excellent grade and Nezir has not,” and it became a big deal. Anyway, the other professor in the other class, I continued there after my professor died. And he looked at my works at the end of the year, and just put his arms like this {explains with hands}, because we had 50 something works, I put them there in order, “Ah,” he shouted when he saw my works. And he gave me a ten, while he gave six to the girl coming from Belgrade, her name was Mirjana Šimunović and these things. Even though I was an Albanian from Kosovo, he gave me a ten. This was fantastic, I had a really good time with the professors in Belgrade, really good.

Then I came to Pristina. I finished my studies there in ‘68 and here a professor from the Shkolla Normale, Engjëll Berisha said, “The call is open, we need a painter.” I applied and got accepted, I worked in the Normale in ‘69, I worked with students. My students were really good, even nowadays when they see me they are all like, “Professor, professor,” they are fantastic, they are really good. I worked there, then I started at the Academy of Arts here in the faculty, I continued working. During one year, ‘69- ‘70 working in the Shkolla Normale, I worked and opened an exhibition at the hall of the Theatre. Hazir Miftari was the director back then, he is deceased now, he died recently, and he accepted my works to open an exhibition there.

And I was really happy that not only once, but several other times he allowed me to open exhibitions at the hall of the Theatre and this was to me… many, many, many good things happened to me in the Normale as well as when I came to the faculty with my students. My students also helped me a lot with conversations in… and now all of my students are professors at the Academy of Arts. And we got along really well, and so I started painting in the atelier, I would paint… I would take them to the atelier again, I saw a villager… he was with a horse car, and I saw him on the street, actually my mother’s house is next to the atelier and I was at hers. And I saw that he was very good to be painted and I said, “Can you come to my atelier, I want to paint you?” “Yes,” he came, and then such a, such a…

And it was very interesting at the exhibition that I opened, a guy came and asked me, he said, “This is very interesting, I can see that he is a worker by his big hands, a worker that…” And I painted his plis with a darker color, not pure white, because it wasn’t white due to the work he had done, and most of the people liked it, very interesting…

Then in ‘77 the call was opened to go to specialize, because back then we would go to specialize. I applied and got accepted to go to Paris, I left my children… I left my deceased husband, doctor Vehbi Shehu, he was a pediatrician, and two of my daughters, Arta was six years old, I left her at the time when she had just started school and the other girl, Visare, was four years old. I think that no Albanian woman did this, it was not in our tradition to go and leave your children and husband, but I went. And I went there, my brother sent me there because he had studied Film Editing in Paris and knew these things. And we went to the professor who accepted the students for specialization, and there were other students from other republics as well, but she gave me the most expensive atelier, the most expensive Academy.

Donjeta Berisha: Were there others from Kosovo?

Alije Vokshi: No, there weren’t, I was the only one. I was the only one. And this is it. I say that it was the most expensive atelier because the most famous painters… Pablo Picasso, George Braque and Montmartre had established a group and my professor, the famous professor, was part of it as well.

Jeta Rexha: And how was your student life there?

Alije Vokshi: …and this group was called Le Bateau-Lavoir. I had a good time there, I had some difficulties because Paris, you know, but I had a good time. And I pleasantly remember these things, they are fantastic. I go to my daughters in London twice every year, and there is a big center with libraries for arts, film and music. I go there and look at the books. Two or three years ago I saw a book in which there was the name of my professor, and the name of a very important professor. When I came here, I wrote the title of the book down and asked my daughter to buy it and mail it to me. When I received that book, I walked around Pristina, “Oh, Alije, such happiness!” I don’t know, a happiness, I cannot describe it, I was really happy.

And these things are what keep me going now and they motivate me to work even more. This is it. In the Academy, I get along very well with the students, they love me very much, very much. They have good conversational habits and are polite. The projects they are doing, and I am not only talking about painters but in general about our youth, they are progressing, this is something incredible. Our youth is really progressing. A professor who was there, Kadrush Rama, his son in London, he is an architect or I don’t exactly know, but he has prospered a lot, he is really, really good… then the other, the son, Sislej, the son of Xhevdet Xhafa, is doing some fantastic performances, fantastic. So, Albanians are very smart and well educated… those abroad are prospering and this is something very pleasant.

In the elementary school Vuk Karadžić, a teacher taught us French, she would sometimes ask us to go to her house to send something or take some flowers. And she had a son, when I was in Paris for my specialization, a painter from Peja, Daut Berisha, a very good painter who opened an exhibition in Paris and we went there, there were some of my friends from Belgrade who had studied something there and they knew me, they were together with the son of my French teacher, and he looked at me, I looked at him too and I said, “Are you the son of the lady who taught French?” He said, “Yes,” her last name was Lukica something, he was really surprised and said, “What a place, Paris!” I had met him during my elementary school and now in ‘77, and this is how it was.

My brother drove me to Paris, we went nearby. Emile Zola was a really good friend of Cezanne, they got along very well and Emile Zola loved Paul Cezanne very much. I am telling this because when Emile Zola wrote the book In the Paradise of Women, in that book he says, “A woman with two children, with a brother and a sister went to Paris from the village after the death of their father, and they went to their paternal uncle’s and when they entered Paris, when they entered Paris, those centers, they were surprised…” And all those things, those streets, when I read that book, it felt like it was talking about me, because the same thing happened to me, my brother sent me there, and I looked… wow… that novel was really interesting, because the same thing happened to me, just like in Zola’s book In the Paradise of Women.

Jeta Rexha: Do you remember your first painting, where the idea for it came from?

Alije Vokshi: Yes, the first painting that I did was a gypsy who I took from the street to draw her portrait. And that painting was bought by, when they saw it in the exhibition. The director of Rilindja bought it. And that painting was taken by someone… that was a really good panting because when people would come to the Academy of Sciences from the Theater of Albania, when writers and everyone would come they would take my painting, the old lady, and put it on the stage, that was like, like… it was liked by everyone.

Jeta Rexha: Maybe a painting or something else where you had a more professional inspiration, maybe?

Alije Vokshi: Portraits were for me, portraits.

Jeta Rexha: So, that was something more special for you?

Alije Vokshi: Yes, portraits and only portraits. Then the professors instructed me, those from the Shkolla e Lartë Pedagogjike, “Work portraits because you do them very well.”

[The speaker stands up in front of her paintings and explains them to those who are present.]

These are two figures, the last portraits that I worked on. Before them the people took their own positions, but these are different, I mean they aren’t the same. While these two others are with light colors, after we declared the independence everything seemed white to me, white, white. Here’s the dancing, there is a woman dancing, these are lighter colors as can be seen. And these are two portraits, the most recent ones.

This is the portrait of my daughter Visare, Visare Selimaj; when she was at the Meto Bajraktari school, I did her portrait. And let me show you the old man. This is the master who was driving his horse car and when I saw him, I stopped him and said, “Can you come to my studio so I can make a portrait of you?” “Yes,” he said. And I worked, and these hands, I mean he is tired, and his plis, the color of his plis is not pure white, but I did it like this because he had worked and he is tired, and the color is like that because of the dust. And when Jusuf Kelmendi saw this in my exhibition, he said, “You can see it in this painting, these hands, tired… a really, really good portrait.” He liked it.

We remained here during the war, my deceased husband and I. Our daughter went to Macedonia together with everyone. And my brother’s house was just next to mine, and his wife came and said, I had my curtains open, she said, “Look, they came!” And I was in the room there, I went to the room where Bylbyl was lying, and I asked him to take a pill because he had heart issues and I said, “Take a pill first,” “Why,” he said, “What happened?” I said, “Take a pill first.” He took the pill and they came, the police and everyone, so we took the chairs and some bread as well as some blankets and went to the roof and waited for them to come. But they had gone straight and now they had returned, we were staying there. A neighbor of ours came to look for Bylbyl, because he had invited us for lunch, he came, “Where is Bylbyl?” He thought that he was dead because he wasn’t answering. At some point, we went out and told him, “It happened like this, like this.”

Jeta Rexha: What are your plans for the future?

Alije Vokshi: To open an exhibition.

Jeta Rexha: Here in Kosovo?

Alije Vokshi: Yes, here in Kosovo.