Part Two

Abdullah Zeneli: And these are the ‘60s, in fact I am talking bout ’61, ‘70s, about that time, which was the time of big events, be it of musical or cinematographic trends. I was lucky to have had the chance to see many good theater plays in the theater of Pristina. I saw the generation of great actors as a child. Katarina Josipi, for example, was amazing. I also followed Radio Pristina, there were radio dramas adapted for children, they were broadcasted every Sunday morning at 8AM. I listened to it with passion, it was wonderful. Then the happy hours with comedy, I adored them. I am a huge admirer of comedy, satire because one fulfills oneself with comedy and satire, this is how one creates optimism.

Aurela Kadriu: What kind of comedy was it at that time? In the radio…?

Abdullah Zeneli: Yes, in the radio. It was very interesting, the comedy hour was every day… There was the comedy hour every Sunday evening, Mixha Ramë [Uncle Rama], which was played by Fitim, Fitim [Fitim Domi].

Aurela Kadriu: In which years?

Abdullah Zeneli: From ’67, ’68 until the radio was closed by the violent measures. There was the happy hour, radio had other very important shows. There were poetic variations, there was the radio drama, I guess the radio drama was broadcast every Thursday or Friday. But there was also the Variacione Poetike [Poetic Variations] show, there was reading of fairy tales for children, I listened to them passionately. Safete Rogova beautifully read the fairy tales for children at 8PM for years in a row, they were actually used to put children to sleep. Just like the trend was at that time to broadcast animated movies before the news so that children would watch them and go to sleep.

Of course, the arrival of black and white TV was an extraordinary event. But besides theater and movies, I also remember when I read War and Peace during Normale, and there was a movie made based on War and Peace and there was a crowd to watch it, it was made by Russians but it was amazing. They had made a two-part movie based on the four volumes of the novel, it was something extraordinary. The writing geniality of Tolstoy was put on, how to say, on screen, to watch it. It was one of the best miracles I witnessed as a Normale student, War and Peace was that. Of course, there were also other movies, but one that has stayed in my memory is a confrontation of Napoleon, the war, the burning of Moscow, the characters, Natasa, Andrei, Pierre Bezukhov. I mean, these are great things that remain in one’s memory but also establish one’s…You see where the world is, you create a vision of confrontations, wars, victims, the burning of the whole city of Moscow.

For example, the strategy of Kutuzov, the Russian general, how he betrays a war genius like Napoleon and so on. I mean, these are small segments which gradually establish the mosaic of the formation of a personality of a person who is happy with achievements in arts as such. As I told you, there was theater, movie and literature , but literature has a central place. But also other parts, figurative arts for example, Kosovo had great painters at that time, it still does. Painting needs advancing, because painting, like music compositions, doesn’t need translation. They are very easy to make their way to the receiver, consumer, to the one who experiences and views them in different galleries. A painting needs no translation, it is what it is, you see it visually.

At that time there were great arts teachers at Shkolla Normale. There was Engjëll Berisha, Kadrush Rama, Sylejman Cara, they were painters of that time, very interesting. And these other art pieces filled the mosaic, as I told you, of aesthetic pleasure which one needs to experience, be it in their imagination, or in their reality which they have to see every day.

Aurela Kadriu: How would you describe the experience of living between two realities, the physical one and the one of books?

Abdullah Zeneli: This is the essence of discontent one faces because of somethings that happen in their lives, because in life, it doesn’t always go right. There are difficult moments, but those moments are compensated for with the other part. I mean, sometimes surreal scenes happen in our real life that one cannot even imagine. Moments of despair, difficult moments, moments of discontent take place and of course one has to be very pragmatic and satisfy one’s life. One must satisfy one’s life with friends, with those one is close too, with theater, movie, everything, free life. I surprisingly never liked vacations, I didn’t know what it meant to rest because I rest by reading, working and achieving, I mean, that is what is always on my mind and this brings me pleasure.

Now I am old, this is a very old age I must say, I am retired, I see success of my generation, of my nation. There is no longer the terrible dictatorship which was in former Yugoslavia and Albania. And of course, one should not expect from the state, there must be initiatives, people must move forward, one must have their vision and work for it. If you don’t work for your vision, you haven’t done anything, you haven’t really done anything. This is the best part of the reality and of the diversity that Balkans has, how to say, the cultures, the clash of cultures, there is always room for positive things, there is always room to respect and love each other. And I guess this is what made me love literature.

I also read Serbian literature without any complexes, I also read literatures of other surrounding nations, Geek, Turkish for example. But of course, French and English-American literatures are in the center of them all, without wanting to exclude other great literatures, so to say, Spanish with Don Kisot is irreplaceable, it was a great pleasure for me to have had the chance to read it as a student of Normale, and many other literatures. I also mentioned the Russian literature in the beginning, great literature of the 19th century with Tolstoy, Dostoevsky, Pushkin, I adore Pushkin.

Aurela Kadriu: Apparently we have something in common, I also love Pushkin very much .

Abdullah Zeneli: He was great! Eugen Onjegin was given to me as a gift in the first year of Shkolla Normale, the brilliant translation of Lasgush Poradeci, Lasargush. This is something great, this is what is fulfilling to one, one must find themselves, they must find what they are lacking and compensate that part.

Aurela Kadriu: Can you tell us about elementary school, in which year did you start? What do you remember from that time?

Abdullah Zeneli: I started in 1959. The school was very close to my house, and I started school two weeks late because there was an activity or something going on in the village and two weeks later it was something absolutely new. The new circle, students of various neighborhoods and…But I had a weird luck, I changed several teachers in the first grade and in fact, my memory of the first teacher is the one of my second grade teacher. I remember her, I had the good luck of having a great teacher, I owe a lot to Bakize Brovina. I owe her a lot, she noticed my literary affinities, my eagerness to cut the village life and turn into something else. And she noticed the details that distinguish a human, I owe her a lot, I owe a lot to Bakize Brovina, whom I consider my first teacher.

After that there were four other grades at Elena Gjika. They noticed my affinities for literature and mathematics there too. My teacher was Fahrije Shita who was terrible in the sense that she was very demanding, but I forgive her for that because she managed to make every student understand mathematics. Because if I am successful in my publishing activities today, it is all thanks to mathematics. Then there was Vedihate Mqiu, my great teacher of Albanian Language and Literature.

Aurela Kadriu: What kind of education system was it that moved you to Meto Bajraktari after four grades…

Abdullah Zeneli: Eh, there weren’t, I mean, after four years there were no more Albanian classes in Meto Bajraktari so the Albanian class had to move to Vuk Karadžić or the current Elena GJika. The Turkish class would continue in Meto Bajraktari until the fifth-sixth grade. I mean, this is how this exchange was done, and moving to the other school was something different. I have a little shortage, as I told you earlier, after finishing elementary school, most of my friends went to gymnasium and I was behind because of the problem that I had with the professional high school in Obiliq, that I betrayed my father, but he forgave me for it. And then Normale, of course, I was one of the best students at Normale.

Aurela Kadriu: Did you go to Normale right after the elementary school?

Abdullah Zeneli: After the elementary school, you go there and apply just like high school, there are admission exams. I even remember that I caught the open call in the last moment, because I had already went to the professional high school….

Aurela Kadriu: What kind of profession…

Abdullah Zeneli: It was the profession, back then there were the mines, an introduction to power plants. They needed professionals of these fields, I don’t know, to work with iron…it wasn’t a matter of mocking, but I was a book person. I was formed with theater, library and everything, so it was a tragedy for me to start working in something that didn’t bring me pleasure.

And I lied to my father, I said that I didn’t manage to pass the admission exam, I took the papers and filed them at Shkolla Normale because it was the only school where the call was still open. And when I went, I am saying this without modesty, when the topics came out, be it in Albanian Language and Literature or Mathematics, I had the answers in five minutes. And the teachers that were supervising us, thought that I was leaving the room as a sign of protest. “No, I am finished!”

So from the extreme of not passing, I went to the other extreme, I finished my Albanian Language and Literature and Mathematics tasks in five minutes. And then there was no problem for me in Normale. Those of my generation know what contribution I gave while in Shkolla Normale.

Aurela Kadriu: In which year did you go to Normale?

Abdullah Zeneli: 1967-68, the first year, that is, fifty years ago…

Aurela Kadriu: Where was the school located?

Abdullah Zeneli: The school is on the way to Gërmia, near the American University, on the other side. At some point later it turned into something else. And then for some time there was the gymnasium of…I don’t know how…

Aurela Kadriu: Of languages…

Abdullah Zeneli: Of languages [Philological Gymnasium] Eqrem Çabej. Then it moved, at the moment I don’t know what it is. I know that AUK is on that way.

Aurela Kadriu: How do you remember it?

Abdullah Zeneli: Shkolla Normale was a great temple of knowledge at that time. It had authority, it had good teachers, very good teachers. It was a kind of nest of nationalism. That is where generations of great personalities come from, they have finished Shkolla Normale at that time. And this made us responsible to be useful to the society. We had the police at school almost every day, I remember it very well. In ’68 for example, the demonstrations…

Aurela Kadriu: Can you tell us more about this part?

Abdullah Zeneli: November 27 was unbelievable, the entire staff, all the teachers, were alarmed, the electricity went off. So, we were somehow forced to come and join the crowds of protester . Our teachers contributed a lot, somehow they had a vision to make us join the ideas of the national renaissance, the patriotic ideas. Even though most of the families were somehow already formed in the spirit of the Monastery Congress.

But it is different when unity makes power, when we were…I know many occasions when they accused us,why was Tito’s photograph torn down or why was another thing was done…

Aurela Kadiru: Can you tell us about these occasions?

Abdullah Zeneli: There were many occasions. They tried to find out who and how they did it. But there was great harmony among students, it was impossible for them to find out who did that action. I mean, it was a collective guilt, nobody can punish the collective guilt, so we always made our way out without any consequence.

And students also read, that was the time when books started coming from Albania, various books, the literature was great. There was a renaissance, in fact, a national renaissance through those books. We would take them hand-to hand. I remember reading the book that was a bestseller [English] of the time, Tradhëtia [The Betrayal] of Kapllan Resuli. It was a book that everybody read. And later, it degenerated, you know how things developed, let’s not get into that chapter.

But Normalja was a great moment in our national formation. Nationalist in the positive sense of the word, not…In the sense of demanding the rights that we were lacking. I remember a great injustice that took place at Shkolla Normale at that time. We had a Serbian deputy director who was very biased. His last name was Kostanović, if I am not mistaken. Before the school day came, because the school was called Miladin Popović, and they wanted to honor, to value…To give a special mention to the student who had read most books in the library.

And he went to the librarian to officially ask for the list of the best readers. He was sure that the best reader was a Serb. He was sure about it. When he saw that I was around thirty books ahead of the potential Serbian reader, he stopped it, the prize wasn’t given. Somehow this has remained in my memory as a great injustice that was done to me. That is where I saw, instead of reflecting, even though he was a Serbian deputy director, instead of reflecting, because no matter what, a reader is a reader. A reader has no nationality, a reader has no profession.

I usually say that the president is a reader, the prime minister as well, ministers, officials, soldiers, policemen too…So, a reader has no profession and a reader has to be valued, the one who has read the books. The prize wasn’t given to me, and I always think about it, why did that great injustice happen. I mean, these are the kinds of moments that remain in your memory.

But I have overcome it, I have overcome it because one has to double it….Since someone doesn’t feel good about me reading, then I will double the number, I will double the reading. And it did me good, that injustice did me good {does the quotation marks with his fingers}, to say within the quotation marks.

Aurela Kadriu: Did this somehow motivate you to organize in the fight…

Abdullah Zeneli: Of course, since, how can I say this, I had suffered that injustice from my grandfather with all the things he went through. An interesting thing, my grandfather who was a soldier in Monastery during 1908-1912, he experienced the First Balkan War. He was held hostage because he deserted the army and he was carried to Belgrade together with the imprisoned and everybody and he stayed in Belgrade for a long time. Surprisingly, the Serbian military forces broke into Kosovo and held the rest of the population hostage. If you search about it on the internet, you search for a march in the center of Terazije in Belgrade at that time, there is a photograph that was taken by the Austrians at that time and you can see the queue of the imprisoned with the policemen on the side, taking them to prisons, and surprisingly, my grandfather saw my great-grandfather after some days, his father, whom he hadn’t seen in four years, he was also imprisoned. My grandfather was held hostage as a First Balkan War desertor, with all the terrible things he had to go through as an inmate of the Skopje Castle, sent to Niš by train as if they were animals, he said that thirty percent of those people died because they got sick on the road, contagious illness such as typhus. It was terrible. I mean, I have all these stories from my grandfather and how we felt while telling them to me. To me they seemed like just stories, but for him they were real experiences. And imagine…

Aurela Kadriu: Why was your great-grandfather there?

Abdullah Zeneli: My great-grandfather, here’s the problem…Because when the Serbian forces broke into Kosovo, they took hostage the few men that were there.

Aurela Kadriu: In 1912?

Abdullah Zeneli: In 1912, very weird. And they met by an absolute accident. My grandfather met his father who is my great-grandfather. Even his name was Zenel, that is where our last name comes from.

Aurela Kadriu: Had this happened because of the events that took place in Albania at that time or…

Abdullah Zeneli: No, no, no. The Balkan Wars, the occupation of Kosovo in 1912, of course the international factor of that time has a finger in all of this too, because you know the separation of borders, then there comes…

Aurela Kadriu: The London Conference…

Abdullah Zeneli: The London Conference and everything that followed. It is terrible, later after 1912 when the first colonists, the first Serbs come to the village, of course I don’t remember it because I was born in ‘52, but we had Serbian neighbors. It was terrible the kind of Serbs they were. Those were the Serbs that were part of the well-known massacres, the one of Prapashticë and so on…

Aurela Kadriu: You had Serbian neighbors in the village or here?

Abdullah Zeneli: Yes, in the village, in the village. I learned Serbian at a very early age. I also told you earlier, I spoke…

Aurela Kadriu: What did you experience from them?

Abdullah Zeneli: In fact, it was hard to notice their tendencies as neighbors, but they were part of the system, part of the system, part of the terror that we went through. As they say, “Long gone, long forgotten.” That is a weird period, but thanks to the international factor, it came to its end.

Aurela Kadriu: I wanted to ask you, you mentioned that you were influenced by those who had come from Gjakova when you moved to Pristina. What neighborhood did this composition exist?

Abdullah Zeneli: The neighborhood near the Meto Bajraktari elementary school, that is where I lived.

Aurela Kadriu: Did this neighborhood’s composition consist mainly of people coming from other cities?

Abdullah Zeneli: It was a totally new neighborhood, you know, near the school, in front of Qafa and the school. The well-known families from Gjakova used to live there, the Brovina, Stavileci, Rudi and other families. I was even friends [with them] at that time, I mean, I had friends from the family of Flora Brovina, I have known Flora since that time. Flutura Brovina, Flora Brovina’s sister was one of my classmates. Then there were other aristocrat families, I mean, that is what they looked like from the perspective of those of us who were coming from the village, they were part of the nomenclature or part of the development. Daughters of music composers, painters, daughters of various directors, emancipated people who were…And I had the luck to grow up in such an environment, and of course this made me take from their good virtues, but I proved myself more skilful, I moved faster, I knew how to steal, just like the bee steals the nectar. I was always ambitious.

Aurela Kadriu: When did you decide to study mathematics?

Abdullah Zeneli: ‘71-’72.

Aurela Kadriu: How did you decide to study mathematics?

Abdullah Zeneli: I knew mathematics best during Shkolla Normale. Mathematics was like…Mathematic is still my savior because at the end of the day, everything in the universe is mathematics.

Aurela Kadriu: Didn’t you experience this as a detachment from books?

Abdullah Zeneli: No, no, no. In the contrary, it helped me. These are two extremes that I brought together. I was very good in technical drawing, it is unbelievable, figurative arts, symmetry, harmony and such…These are rules that, I mean, just like there is harmony in figurative literatures, in literature, in writing and everything, same goes for sciences, there is a system, an order. One who achieves success always knows how to make themselves conscious, because they know how to create harmony. If you create the kind of harmony that the door is a door, one enters something through the door and not through the window, window is there to see the world through it, the window is to get light through it, to get air through it…I mean, you must know the importance, weigh or the dedication of every object. We are lucky, I am talking about my generation, that we have managed to somehow confront or bring together the good tradition, the great wealth of philosophy and people’s wisdom with the international literature.

I was lucky enough to bring these two together, just like I managed to love science and literature the same way and know them as well. It is interesting, there is a book that hasn’t been published yet, I have translated it years ago, Aristotle’s Rhetoric, it is a great masterpiece speaking about the stories that I have heard from my father. I mean it is in the subconsciousness of the people that at some point in our history we used to have universities, development, schools, palaces, we had a very well developed urban life.

So to say, Sibvoc, my birth village is very near the very famous antique locality of Kosovo, Vendenis. And when I went to see that, I could see for myself where the street of that two-thousand year old city was. I went there before the grain was ready to harvest, when it is still green,and on one side of the grain’s color I could see where the street was and then the stories that, “It was like this, the cats walked on the walls,” and then there is the interesting part of vegetation. Historiography speaks also about it, that there was a very big city there, at a certain time in history. And there are debates about where the center of Dardania was, whether it was Skopje or Pre-Justiniana, the locality of Upliana, or whether it was in the area that is known as the Gallap area, that is a part where if you dig, there is no way you won’t find something. It is a mystery that archaeology will discover soon.

Aurela Kadriu: Are there any signs?

Abdullah Zeneli: There are many signs, there are many signs, absolutely. There have been a lot of mines, there were….The deep [mines] are of Llap, the canyon is extraordinary. There were localities, for example the village of Pollatë, for example, it was named after the fact that there were palaces there. There was the mine of gold and silver, it is thought that there was a city so-called Kosova in the canyon that is at the mouth of river Llap. I have grown up listening to such legends, stories from my family on my father’s side, but also when we went to my paternal uncles’ for visit, in the village of Llapashticë, upper Llapashticë. The stories with katalaj that were called diva, with the giants and with all those, they seemed as just stories to us but if you analyse them, if you go into literature and mythology, they are things recognized by the science. I mean, science recognized early civilization, mythology recognizes them as well. We all grew up within that world and this create the vision, or how to say, the widening of the horizons for us to see the world differently and to develop our profession or the pleasure of reading, so to say.

Aurela Kadriu: Did you finish University…You were in Pristina, right?

Abdullah Zeneli: I had the luck of working with the book and it was difficult for me to continue studying Mathematics with correspondence and so I started studying literature. I had no problems studying literature, of course, I eventually graduated, my grade point average was a 8.5 to 9. Maybe it is a lack of modesty to say, but in literature, it was something extraordinary. When I went to exams, I didn’t consider myself a student, I considered myself in the same level with the teachers. I confronted my teachers, I disagreed with some approaches or points of view. I was very critique of socialist realism, of that biased literature, I had the good fortune of reading books in other languages as well, especially in Croatian and Serbo-Croatian, there was not a book that was translated during the time that I frequented at the fairs….Of course, later on there were the international fairs, where through French, I managed to…

Aurela Kadriu: When did you start studying Literature?

Abdullah Zeneli: Right after coming back from the military service, in 1976.

Aurela Kadriu: Where were you for the military service?

Abdullah Zeneli: In Leskovac. I was in Leskovac for fourteen months.

Aurela Kadriu: How was it?

Abdullah Zeneli: Well…like in the military service! I was lucky that I wasn’t there in ’81 because I would have returned in a coffin, just like it happened. I was a fighter of the cause, I forced them to let me watch the television in Albanian, I fought for my right, I decided not to do several military exercises but watch the Albanian shows instead. I was a fighter of the just at that time in Leskovac, I am surprised, if I was there in ‘81, my fate would be totally different.

Aurela Kadriu: You said you quit mathematics in ’73?”.

Abdullah Zeneli: Then I started working at Rilindja.

Aurela Kadriu: In what position?

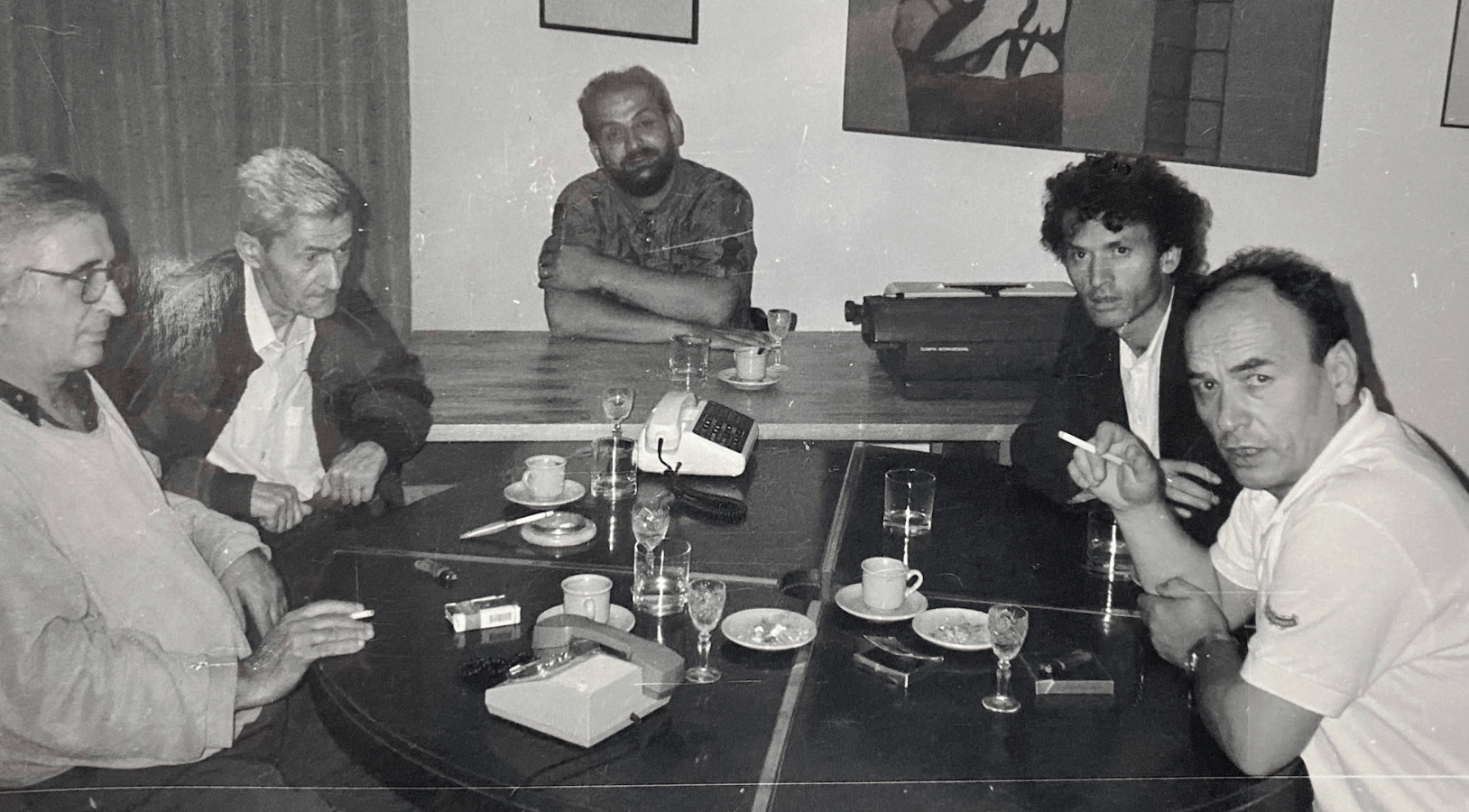

Abdullah Zeneli: I was in charge for book selling, I mean, I was engaged in book selling. And I slowly managed to get promoted in the mid ‘80s, in ’84 I was given the title of the head of book sales, I was very good at book selling, I mean, at the book distribution, always with the vision that I would also deal with the creative part of the book. I wrote, I never stopped writing. At that time, I knew the best writers because I was there with them at Rilindja, Anton Pashku, Ali Podrimja, Rifat Kukaj, Fahredin Gunga, the best writers of that time. From ’78 and on, I was a good friend with Ibrahim Rugova for example, Rexhep Qosja, with all the people of literature, and I am within that, no matter that I never stopped loving mathematics and other sciences, because they fulfill each other, they create the general harmony.

Aurela Kadriu: How was the political situation reflected in Rilindja?

Abdullah Zeneli: It was very difficult, very difficult and at the end of the day, it was that ruling power’s goal to destroy the development that had been achieved until then…Because all that happened in ’81 and after that was them stopping the development of the Albanian people in the former Yugoslavia. It was terrible. But the foundation had been established, and we are a nation that survives catastrophes, we survive tragedies.

Aurela Kadriu: Tell me more details about how you experienced that…

Abdullah Zeneli: It was very, very difficult because they took us out of the building of Rilindja. The publishing office was in the ninth floor, they took us out of the ninth floor.

Aurela Kadriu: When?

Abdullah Zeneli: ‘92, 1992. It started in ’90, it started…

Aurela Kadriu: In ‘81…

Abdullah Zeneli: In ‘81 the stopping of the relations with Albania was terrible, I mean, with Albania…

Aurela Kadriu: You were exchanging with Albania until that time?

Abdullah Zeneli: We exchanged publishings, books, we would take tons of books from Albania every year and we distributed books, especially the translated literature but also original literature, various novels, books, but the literature translations were great.

Aurela Kadriu: Why did it happen, how did that stopping of relations with Albania, reflect later…

Abdullah Zeneli: They used the events that took place as an excuse because first there were students protests against bad conditions and so on, but that was a game of the ruling power, they wanted to turn it into something different, I mean, they wanted to make it look like they were counter-revolutionary and wanted to overthrow the constitutional order, so detentions and restrictions began, I mean, that is how the collaboration with Albania was stopped and in fact it was a clear signal that the development of Albanians within Yugoslavia would be interrupted because a big explosion started. You know the Academy of Sciences, Kosovo advanced in 1974, it was almost a republic so they were bothered by the development. Kosovo was developing in the sense that factories were opened, the industry was developing. All the republics from Slovenia to Macedonia were forced to invest in Kosovo. Kosovo started taking its steps slowly, of course, very slowly compared to the trend that it was supposed to move [at] according to, but however, there was movement and they were bothered by it. That is why they took ’81 as an excuse, and big problems started, [those] two-three years were very difficult, you know, very difficult, then somehow we slowly started breathing again, and the protests started, you know in ’87, ’88, the miners’ protests or when the changes of the however little autonomy that Kosovo had, they wanted to revoke that too, of course there was a nation that could not tolerate that, and it escalated into what we witnessed.

Something terrible was foreseen for Albanians from Kosovo but the social organization and the developments of that time didn’t want the war in the beginning, and it is something good that it was moved to Bosnia and Croatia, what was thought to happen in Kosovo according to the voices of that time, because I wasn’t part of the, how to say, leadership of that time and I didn’t know, but what was thought to happen to Kosovo, was moved to Croatia and Bosnia. Then slowly, the time came for it to be achieved with guns here too.

Aurela Kadriu: Can you tell us about, when they expelled you from your job, from Rilindja, when Rilindja was closed.

Abdullah Zeneli: Rilindja, in fact the processes started in ’90, I mean and it kept becoming more difficult every year, in ’92 and ’93 they started also taking us out of the buildings or we had to pay rent or…I mean, that was terrible.

Aurela Kadriu: How did you function later, did you continue?

Abdullah Zeneli: We moved, just like schools and universities that moved to basements-schools, we started organizing outside the building of Rilindja and we survived. Of course, at that time I also used the strategy of the Buzuku publishing house which I registered right after Rilindja was closed in 1990. I didn’t register it in Pristina because they wouldn’t let me do so, I needed a building and some other very strict rules in order to register a business, you also needed to have money deposited in the bank, it wasn’t like today when you can start an enterprise without any money at all. But luckily, there were very good people, I went to Gjakova, to the Economic Court in Gjakova, I registered my business in Gjakova, and this connection with Gjakova helped me to remove the marks, I mean, so the ruling power could not stop me from working, I mean, one had to be very skilful to do that. I managed to do that, it wasn’t something very brave of me, but it was something smart, I mean the foresight to know was everything…

Aurela Kadriu: Did Rilindja continue under the same name then?

Abdullah Zeneli: Rilindja continued until after the war, I mean the name was saved, the staff was saved, everything. In ’99, after the Serbian forces left, a whole different change started.

Aurela Kadriu: Were you part of Bujku as well?

Abdullah Zeneli: Bujku was a camouflage of the daily Rilindja because Rilindja was restricted, but after the war Rilindja was published as Rilindja.

Aurela Kadriu: Were you the same people?

Abdullah Zeneli: Yes, we were the same people at the publishing department, but there was a whole different change, maybe it was a matter of people’s egos or somebody’s thirst for power, some other problems showed up. I had no time for such things because they weren’t right with me, I know what I contributed to save the literature and the good name of Rilindja, and freedom came in ’99, they continued, they didn’t want my help, fine.

Aurela Kadriu: What happened in that moment?

Abdullah Zeneli: They continued for some time, but not much time passed [before]and they closed it even though it was within the Ministry of Culture, which was established in 2002, and there were six salaries that were paid by the ministry. The ministry stopped the publishing activity, I wasn’t part of that group of six people, if I was part of that group I wouldn’t let them stop the publishing activity, I would use all the mechanisms up until the United Nations, but those who remained didn’t know how to do it, then I continued with my stuff. I have managed to create the Book Fair in ’99, I managed to help the publishers from Albania, they were nowhere, I mean we are talking about ’95, ’97, ’98. The first Fair that was organized in Tirana in ’98 is a merit of initiatives from Kosovo, there are original documents that we have signed in Frankfurt, we worked a lot around the homogenization, around creating good relations and of course, today the literature is one of the best activities. Literature has turned into an industry today and of course there is competition, I see competition as a positive thing because competition brings quality, quality brings quality, and in the end the reader benefits from all of that.

Aurela Kadriu: Where were you during the war?

Abdullah Zeneli: I was in Korça as a refugee for one hundred days.

Aurela Kadriu: In Korça?

Abdullah Zeneli: Yes, in Korça. Because we stayed in Bllacë for one week and we didn’t know anything when the order to empty the camp came, they just put us in buses and we didn’t know where we were going.

Aurela Kadriu: When did you go to Bllacë?

Abdullah Zeneli: I went to Bllacë in around March 30-31, around that time.

Aurela Kadriu: I mean, in which year?

Abdullah Zeneli: In ’99, right after [March] 24. The bombings of the evening, we stayed in Pristina for four-five days and then the police forces came and took us out and the marching from….

Aurela Kadriu: You left after the bombings?

Abdullah Zeneli: Yes, four-five days after the bombings. I would never leave had the forces not kicked us out. One week in Bllacë was terrible. In Korça I was lucky that….The literature saved me in Korça as well, I would read two hundred pages a day, it saved me from, from…Because we left everything behind, we didn’t know what could happen, we left everything we had for the sake of our own lives, they remained behind us and we didn’t know whether they would get burned or not.

Aurela Kadriu: You left the houses?

Abdullah Zeneli: Yes, yes, we were, I mean the police and military forces came to every neighborhood and…

Aurela Kadriu: Which road did the queue take?

Abdullah Zeneli: It went straight to the railway station, that is where they would gather us and the next day they put us in trains, we had no idea where we were going.

Aurela Kadriu: Through which roads did you go?

Abdullah Zeneli: We went down the street where the Serbian church is now, to the main street, to the monument, to Qafa and the straight road…

Aurela Kadriu: The monument?

Abdullah Zeneli: The monument, the triangle that is there. I saw a very weird scene there, near the bridge where the roundabout that takes you up to the New Municipality building in Dragodan is, in Arbëri as they call it now. There I saw a macabre scene that I will ever forget. A Serbian police, soldier, they had thrown the flag of the United States of America on the ground, and he was stepping right in the middle of it, he was armed to the teeth, when I saw that scene, I was optimistic because I thought they were crazy and freedom would come one day, because mocking the American flag in that way was something intolerable, I will never forget that scene. You know, the embassy, the American consulate wasn’t very far from that and looks like they had taken the flag from the consulate and it was a very big flag, the one who was armed to the teeth was stepping in the middle of it, I don’t know whether he was a soldier, a policeman or a paramilitary. We didn’t even dare to watch him because they could take you from the queue and shot you right there, it was a terrible experience.

Aurela Kadriu: Did you go through Qafa?

Abdullah Zeneli: Yes through Qafa to the railway station, that night…

Aurela Kadriu: Through the road where Xhevdet Doda Gymnasium is currently or straight?

Abdullah Zeneli: No, we went straight, I mean, there, where the railway station is also currently…

Aurela Kadriu: Did you spend the night?

Abdullah Zeneli: We spent one night, until the morning, and we couldn’t even sleep because we didn’t know what was happening. We could hear gunshots from up in Arbëria and to be honest, I also asked my wife to cover our children because I thought they were coming to shoot us, I really thought that they were going to shoot us. This was the physical conditions we were in, I was prepared that they would come to massacre us because we were in the open sky and there were gunshots coming from all sides and we were under, as they say, God’s mercy. The trains came the next morning, they put us in trains as if we were animals, I counted and there were 24 people in one wagon, and we didn’t know whether they were taking us to Serbia, to Niš, to Kraljevo. In Fushë Kosovë it took the direction to Skopje and I was optimistic, we were lucky because those who were in one train before us had gone through many tortues, we were lucky because there were no tortures in our train even though I suffered a separation of the family, half of the family remained in one wagon and the other in the other because it was impossible to find each other in that crowd of people, we took off in Hani i Elezit, I didn’t know what had happened to my family or to the other part.

Aurela Kadriu: Did you cross the border on foot?

Abdullah Zeneli: On foot and then we went to Bllacë through railway, there was a field. I mean, how to say, no man’s land, the one between two borders, and for one week I saw scenes…There were two-three hundred of people there.

Aurela Kadriu: How did you unite with your family then?

Abdullah Zeneli: We found each other when we left the train, they were in one other wagon and when they came out of the train of course we found each other. We didn’t know what was happening in that first night, one night it was raining, it was cold, it was a winter, a terrible winter. It wasn’t winter because technically, it was already spring, it was around March 29, 30 and April 1. Then it was over, on April 6 we went to Korça. Had the order to leave Bllacë not arrived before the weather got warmer, cholera and other hard diseases would spread because the weather started getting warmer and there was a lot of trash. There were two hundred thousand people and imagine how much trash there was in that camp. I have described all this in my books Toka Shqiptare [Albanian Land] that I wrote while I was in Korça and then it was published in series, I didn’t know they would turn into a book. I wrote my experiences every week, be it from Bllaca or from my life in Korça, or reminiscences of everyday life, I would write them and publish them in a local newspaper in Pogradec…We stayed there for one hundred days, the publisher Afroviti Kusho asked me to leave some pieces [unpublished] but because it happened that way that [it did],the NATO forces broke into Kosovo, and everybody was returned by airplane. They took us from Korça to Kukës by a NATO helicopter.

Aurela Kadriu: Why?

Abdullah Zeneli: There were NATO forces with their helicopter and they brought us here, the helicopters were huge. I counted, there were 26 people on board, I mean, there were only two families returning from Korça. We were actually coming from Drenova, which is the birthplace of Aleksandër Stavre Drenova, who is the writer of the Albanian National Anthem, then there is Boboshtica and then Korça. That was somehow the cradle of Albanian culture in Korça and I integrated very quickly in cultural circles in Korça, with theater actors, writers and musicians, they were even surprised of how we knew that mentality, that philosophy, that development. Korça is one of the cities that has a great cultural tradition. I went to visit the first girls’ school, the first Albanian school, the school of Pandeli Sotiri, there was not a spot without a monument in Korça. This was something positive in all that tragedy we were going through as refugees, I mean it was something we fulfilled our lives with. Those were the circumstances in which the book Toka Shqiptare was written and then it was published in series. The publisher collected them in one book, and that is a book about my experiences in Korça, there are some reminiscences of my earlier life included as well.

Aurela Kadriu: Where did you stay in Korça, did you stay at any family’s?

Abdullah Zeneli: A family volunteered to give us a space, it was an empty apartment because its owner was living and working in Greece. It was a studio apartment, it had a kitchen, one room and one kitchen and I lived there with my whole family, back then my mother was alive too and we lived there for one hundred days. After the [NATO] forces came, my mother together with my sister and my son came right away but I had to stay because I still had something going on , I was trying to finish the drama about Mother Teresa, I wasn’t lucky enough so I had to return, there was an order that forced us to return and that is how the story with the helicopter happened.

Aurela Kadriu: When did you return?

Abdullah Zeneli: It was around July five-sixteen…

Aurela Kadriu: How did you find…

Abdullah Zeneli: Luckily, some damage had been done, but not in the scale that I had feared it. They had stolen computers, a printer or something, but my most important wealth, my books, the library was safe. I used a strategy there, I threw books on the floor from the shelves so that when they came to see, they would get the impression that somebody had been there before them and that those books were unimportant, so I threw them on the floor, all the books, around ten thousand titles and I am speaking about my personal library, not of the publishing house because they were somewhere else. It was a kind of garage that wouldn’t give the impression of a place where there were books, and so it went unnoticed, knowing how to camouflage things is a skill too. You know, even tanks are camouflaged with some leaves, branches, so that others cannot know that it is a tank, I mean, you should also use art because the martial art is very interesting, it is an art in itself, it is a philosophy in itself and one learns by reading.

Aurela Kadriu: How did your life continue after the war?

Abdullah Zeneli: It was actually very difficult after the war, we needed loans, first banks settled here. I remember the first loan I took, we organized the first book fair after a short period of time, the market with Albania was open, opportunities were created, books came from Albania. The goal was to help publishers, no matter that development also has some problems, there is competition, somebody walks faster, they use other alternatives and I had no ambitions to, how to say, eclipse anyone’s sun, I worked slowly with loans, my ambitions were to save the substances, to walk, to have a slow but good development.

Aurela Kadriu: What kind of books have you published up to now? The ones that you have authored?

Abdullah Zeneli: I have around six published books, I have around seven-eight drafts, be it stories, novels, drama that are waiting to be published. I have around three-four poetry books published, I am also very active on Facebook, I often post poetry there. Poetry is an expression, a release, a discharge of emotions and everyday barriers and it is a pleasure, art is something, art satisfies your life and now I am satisfied , especially now that I am retired, I live with the creativity, I live with literature, I live with the book, culture, developments in the field of art. Albanians have moved forward, especially as far as books go. But as a publishing house, I have managed to publish up to seven hundred titles which is very interesting, of course, the financing is mainly personal and I also try to help the young. My tendendency and goal is to help the young, knowing what I had to go through myself without ever having any idea for a solution, and I know that sometimes your field of activity can get very narrow. I like to support the young, and I think I have managed to. I never ask the authors for money for publishing, I try to help with my knowledge in the improvement of every publishing, and I think I have managed to also do good in the field of translation because I publish the best books that are a world trend, I publish them very quickly in Albanian.

Aurela Kadriu: Do you translate them yourself?

Abdullah Zeneli: No, I have translators. I don’t have time. I could translate from French, but I have to deal with the vision, plan, the organizing. And now for example, these last four years the best novels of French literatures that have been honored with Goncourt which is the Nobel of France, I have gotten the copyrights to publish and I have published them as a publishing house. Or for example, the last Nobels, these last four-five years I have gotten the copyrights to publish Padje Podjamo, Svetlana Aleksievic and many others. So, I catch world trends and other novels that are very trendy in the world, I am talking about literature because I live by the achievements of literature, for me it is a very great satisfaction and I cherish the respect of famous world publishing houses, especially with those of France and Paris Gallimardi…La Marjon and other publishers, Akcyd for example, I have a very good relation with Akcyd, I have published the most famous authors of France actually, Matijas Enar and the Goncourt winner Metrik Vujar with whom I have very good relations but what is the most interesting is the moment when Emmanuel Macron won the elections last year, he assigned the publisher of Akcyd as the Minister of Culture, I mean this was his vision…

I had the chance to befriend him during the ceremony of the opening of the book fair of Frankfurt where France was a guest too. Emmanuel Macron and Angela Merkel were part of the opening ceremony and it was a great pleasure to have the invitation by the organizer to attend such an event. It was a pleasure for myself because I have contributed something in the field of the book, that is why the organizer invited me to be part of that activity. Or, for example, Salon De livre which was held one month ago in Paris, I met, President Emmanuel Macron wasn’t that far either, but I used the chance to get the French Prime Minister Eduard Filip sign a book. I got the publishing copyrights and the book is ready for the next book fair of Pistina, the book will be ready after two weeks and it will be accessible by our reader, it is a very interesting title. People who read it will catch the phenomena of reading which we need to affirm and encourage the reading habit because our education system, family, environment and our society has to do whatever is possible to create and cultivate the reading habit, if we have achieved something…Because myself as a village child who came to Pristina as a four year old has achieved something, and if so, I have achieved it thanks to reading.

Aurela Kadriu: If you have nothing to add, Mr. Zeneli I would like to thank you for the interview.

Abdullah Zeneli: Thank you! I tried to broadly unfold a life with the book, I would be very thankful if I managed to say anything. Thank you very much!