I told him, ‘I have come to submit a topic that does not exist: Byzantine Aesthetics.’ He jumped off his chair and said, ‘Who has misinformed you? How come it doesn’t exist? (laughs) ‘Alright’ I said. He said, ‘Write me an outline.’ I had already started reading some stuff. When I submitted my draft, it had two-three topics that I wanted to work on. And he looked at it and said, ‘You will end up writing a book’ (laughs). I said, ‘No, no, just like that…’ He said, ‘Ok, go ahead!’

[…] Somehow I wanted to become a Byzantine scholar, learn ancient greek. I started taking some courses there, but we got into the ‘80s, the political circumstances changed in Yugoslavia and my status as a…. In ‘78, I was employed at the Philology Faculty in Belgrade, in the Albanian Language Department. Now, you know, we were all caught up by the politics and these things, and to me no longer seemed interesting to study that, you know. Although I always had the ambition to finish it, to publish my work, to work more on it. Only after 20 years, you know after 1999 I published the first volume of ‘Byzantine Aesthetics’ in Albanian.

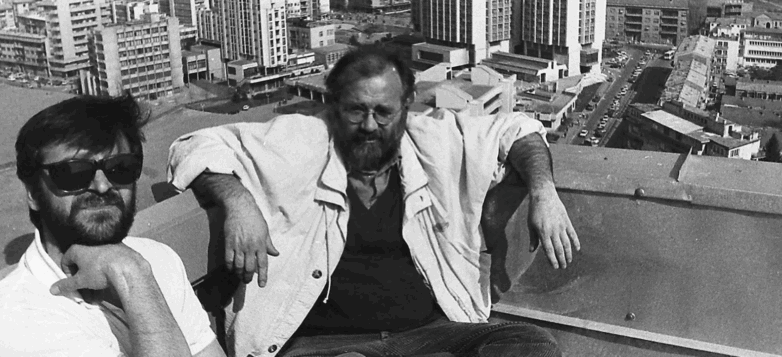

Shkëlzen Maliqi was born on October 28, 1947 in Rahovec and lived between Prizren and Pristina. He completed his Philosophy studies in Belgrade, Serbia. He is a philosopher, art critic and political analyst, whose books have been translated into Albanian, English, Italian, Spanish and Serbian. During the 1990s, he was directly involved in politics by founding and becoming the first party president of the Kosovo Social Democratic Party. Since the 1980s, he has continuously contributed to the culture sphere and important local and regional media. Currently, Maliqi leads the Center for Humanistic Studies Gani Bobi and lives in Pristina with his wife.