Dimal Basha is an Albanian-American who was born and raised in Kosovo. He moved to the USA in 2007, where he obtained his Bachelors and Masters degree. He works as a Data Quality Analyst for the Federal Court, but also has published work on security issues and writes columns for various daily newspapers in Kosovo.

MY GRANDMOTHER, THE OLD MAN IN WHITE, AND I

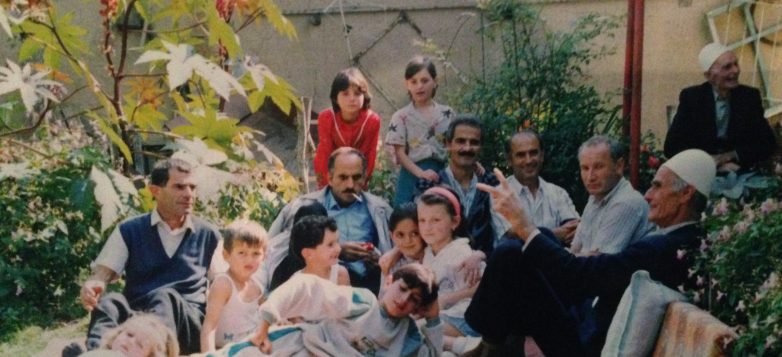

It was something of a tradition for my mother to spend the whole summer vacation with her two sisters. My father, a refugee from Albania, could never visit his family. We gathered at my uncle’s house in the village of Balaj, five kilometers from Ferizaj. Grandpa and grandma lived there with two uncles, their wives, and their eight children. We were three children, but when we met also with the eleven members of my aunts’ families in Balaj, we became a large extended family of thirty. Since none of us had the financial means to spend proper vacations somewhere else, going to my uncle’s country house was the closest thing to visiting a resort.

It was a three bedroom mudhouse and we occupied its every corner throughout the summer months. At the end of the frontyard there was a separate building, the oda, or the men’s room. It was larger than any other room and no woman was ever allowed there. Impressed by pictures I saw in history books, I thought that this officially segregated room resembled the Congress of Lezha, where five hundred years ago our national hero Gjergj Skanderbeg gathered all the Albanian tribes to fight the Ottoman Empire. At night though, due to lack of space, the oda was unceremoniously converted into a sleeping camp for all the kids.

We were on vacation having fun, the kids playing and the men sitting in their oda, but the women were busy with a tight working schedule. They were the first to wake up in the morning and the last to go to sleep, like workers in the cooperatives of Hoxha’s Albania. This routine seemed normal at the time, but now I can freely compare it to that of a North Korean labour camp.

The women’s toughest task was to put kids to sleep in the evening, an absolute nightmare and an impossible mission. In order to accelerate this process, our grandma often intimidated us with this threat, “Sleep, or the old man in white will come!”

My vivid imagination did a great job visualizing this old man in white. If only grandma knew the scary figure I conjured in my day dreaming, I am pretty certain she would have been terrified too. I never doubted that she meant no harm to us. I am sure that she, and all the other women in the house, were desperate to get us to bed quickly because they were all exhausted. But her threat had a traumatizing effect and her intention boomeranged.

As I lay in bed, the figure of the old white man took shape in my mind and my eyes began to scout the room in search for him. When the wind pierced through the cracks of the old wooden windows, I shivered in fear and stayed awake.

It must have been the summer of 1986. After a long sleepless night, I complained to grandma that whenever she reminded us of the old man I was unable to fall asleep. She felt bad about it and began to caress me. I reveled in her warm caresses, until she suddenly lifted her head, as if she remembered something and said, “You have to learn some prayers, then you will be fearless. Whenever the devil comes near you, you will say the prayers, and he will leave.”