Part One

Aurela Kadriu: If you can introduce yourself first and tell us something about your early childhood memories? The place in which you were born, what kind of setting was that and whatever you remember from your childhood.

Ilir Gjinolli: My name is Ilir Gjinolli. I was born into an old family in Gjilan, they say that my family is the one who founded the city, the Gjinolli family. My parents were educators. My brother was a mathematics teacher while my mother was a teacher of lower grades of elementary school. The memories I have of the city I was born are mainly connected with my elementary school life, but even more with the high school because that is also the time when one forms themselves. One forms themselves in the sense that they create the first social relations that last the longest.

From my early childhood I remember that when I went to the first grade, I was determined to pick my teacher even though I remember that my teacher taught in a school that was twenty minutes away from the closest school, which was five minutes from my home. However, I decided that my teacher would be a priority over the walking…Teacher Sinan, he was someone of a great influence on my formation, especially as far as writing and reading go, which were of course developed further in the higher grades when I changed schools, that is, when I came back to the school that was closer to my house, but also in the gymnasium, in the gymnasium of Gjilan.

I remember that I was hesitant when I went to the first grade because of course it was a big change, I didn’t even go to school for two days. Since my mother was a teacher at that school, she told my father, “Ilir doesn’t want to go to school.” “Alright,” he said, “I will take him to school tomorrow. We will go together.” But then I changed my opinion and said, “No, I will go on my own.” And this is something that connects me with the beginning of my education, I mean, with the first grade in 1968.

Something else I remember from my elementary school is my class monitor when I was in higher grades who affected my formation, in the sense of orienting me towards technical sciences. I am talking about my technical drawing teacher, who insisted that the students learned the culture, I mean, he wanted to teach the technical culture of technical drawing, workshop exercise, I mean, working with models, to teach us how to work on a construction model, a model in electric technology, machinery…I mean, this had a big influence on my formation as a person who later was oriented towards technics.

Of course at school the memories also come from playing with friends and sometimes friendships are created because of what you play or what sports you like and that makes getting close to each other faster. I mean, I liked sports even though I wasn’t physically prepared to pursue it as a profession, but however games such as soccer and basketball were places when our friendships always got stronger.

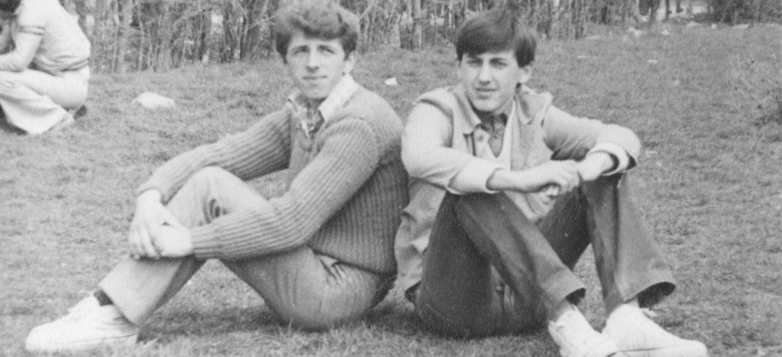

In gymnasium, I was part of a classroom of students who were very close to each other, our friendship continues to this day, we often gather with my high school friends, I often go to Gjilan exactly because of my friends. For four years of gymnasium, I can say that we were the type of friends that were separated only by sleep.

Aurela Kadriu: I would like to still stay on childhood, then we can talk about gymnasium as well. How many siblings did you have?

Ilir Gjinolli: We were three children. I am the youngest in my family. My sister Teuta is an electrical engineer, my brother Agron is a civil engineer, he has been living in the United States since 1995. As a mathematics teacher, my father was a great influencer for the fact that we decided to study technical sciences, maybe because he thought that engineering is a profession that opens many doors and it is easier to find a job with it. But also for us as students in elementary and high school, it was somehow shameful for us not to know mathematics, since our father was a professor in Gjilan, he was at Normale then in the Technical High School.

My sister was six years older and my brother is two years older than me. I was always closer to my brother, because of the age and the games, and then during our studies, I joined him, we got the chance to study together for three years and we were connected to each other even after our studies because our professions were similar, I am an architect and he is a civil engineer. We were, I am still, I continue being a university teacher, he used to be but he moved to the United States in ’95, because he found himself there. No matter his attempts to return, he remained in the United States of America.

As children, we never had any kind of how to say, we didn’t fight with each other since our sister was older, but however, I remember that we didn’t fight with each other as children. Maybe the time was different as far as education goes and children fighting with each other was more common than it is today. But however, I remember that we rarely fought with each other for something or…

Of course I was the youngest one and I tried to walk in the steps of my sister and brother, especially at school or…I often received their help when I needed it, when I had problems with a certain subject. For example, I learned to play basketball from my brother, he had learned before me, then I learned by following him, hmm…What else do I remember…

I remember that I couldn’t wait for winter to come and the snow to fall. A hill was near our apartment and we had a huge wooden slide which was, in fact, nobody in the city had one like that because it was bought somewhere in Slovenia. It was a huge slide which could fit three people. Each time it snowed, we climbed to the hill, it was like a ritual of people living in that part of the city, to gather in the summit and slide down, where the bus station is currently located. This was something that I repeated until the first or second year of gymnasium. And then, I gave my slide to the children of my neighbor.

Aurela Kadriu: Who brought it to you from Slovenia?

Ilir Gjinolli: If I am not mistaken, my father bought it in Slovenia or asked someone to do it, or bought it in Skopje but it as produced in Slovenia, I am not sure.

Aurela Kadriu: Did your father travel at that time as a professor, did he get to travel?

Ilir Gjinolli: My father was politically persecuted in the ‘50s, I mean, he was politically persecuted since his studies In Belgrade and then he carried that with him even when he returned to Gjilan and started teaching. So, in 1958, when my sister was already in life, he was forced to move, actually to escape Gjilan and move to Skopje at his paternal uncle’s, together with my mother and my sister. He stayed in Skopje until 1961.

Aurela Kadriu: Why was he persecuted?

Ilir Gjinolli: He was politically persecuted during the time of Ranković, he was always under pressure. Back then there were many, how to say, situations when people got executed, a little moment of carelessness was enough for the ruling power to execute you. My father experienced such a case one evening, they called him exactly to the hill that I told you about, where we went to slide, they called him for a meeting there. My father realized that their goal was something else and he spoke to my grandfather and they moved to Skopje directly, then my mother joined them.

It was mainly because of my father’s political views, I mean right after 1950 when the elections and the first registration of population took place, there was a big struggle of Serbs to pressure the old civil families into registering as Turks. At that time my father was in Belgrade and wrote a letter to his parents saying, “If you register as Turks, do not consider me your son anymore.” Of course as the UDB functioned back then, they opened the letter and read it and they always kept it as a reason to persecute my father.

But also when he came back because the number of Albanian teachers gradually increased, I mean, there was a need to open schools, departments, high schools in Albanian. On the other hand, the pressure of the UDB aimed to discourage Albanians to pursue education. He returned to Gjilan in 1961 when Normale was opened and he worked for Normale from that time up to 1970, or ’71 if I am not mistaken, when he started working for the Qualifying Center for Production Workers, where he taught mathematics and professional practical education, it was like a crafts school, something like that.

For some time he also worked in Pristina, in the Hajvali neighborhood and at the Meto Bajraktari elementary school, if I am not mistaken, but he returned to Gjilan again. From ’77 to ’87 when he retired, he worked at the Technical School.

Aurela Kadriu: And how did it affect… You mentioned it earlier that he was also persecuted during the time of Ranković, you started school in ’68, how, did it anyhow affect you as a child?

Ilir Gjinolli: I was young, but certainly my brother and my sister weren’t able to…I don’t think they were able to understand what was going on, but also our father never expressed that at home. I only remember for example in ’73, if I am not mistaken, he was forbidden to teach for four years, exactly because of political reasons. I remember this period because he wasn’t allowed to work in education and started working for a construction enterprise until they allowed him to return to education in ’77. To be honest, we weren’t much affected by it because we were children and we didn’t understand these things. But I am sure my mother understood it, my family, his parents, my grandmother and grandfather as well as my paternal aunts and uncles.

Aurela Kadriu: What was the role of your mother in this whole situation? How do you remember your mother…

Ilir Gjinolli: My mother, my mother was how to say, like a second teacher at home. I mean, each time we faced difficulties or wanted to ask something, or eventually had any school requests, she was there to support, or explain the situation to the teacher, I am talking about myself since she was close to me [at school]. Of course, then there are other usual issues connected with parents, but however when you have a teacher at home, of course it was easier for us to overcome difficulties with homework, poem memorization and what else…I mean, it was something very pleasant for us as students.

What else can I tell you about my childhood. What my parents always had, and that we always saw as a commitment of theirs was to study, I mean, to be good students, to understand that education is a must. I remember that my father always said that education is the only way for the Albanian nation to prosper. I mean, education was a kind of life commitment and I think they left a mark on us as well, I mean, what I do and what I have been doing my whole life since ’88 until now at the University is that I have tried to…At least to transmit the knowledge that I gained, but also to open new horizons for students, I mean for them to be able to have choices. I have never been too strict, the way we are used to studying from the early times, I mean, one direction, “This is this and that’s it.”

I have shifted my approach long time ago and I think that what I have done was somehow always based on what I inherited from my parents. My parents always paid attention to health, they always worked to take care of our health through healthy food. Money was very limited at that time, especially for those in education, so they took very good care not to spend on unnecessary things. What my father always insisted on was to spend at least fifteen days by the seaside in Ulcinj, because of the sea and sand… Such thing wasn’t that easy for that time, but my father was committed to letting us enjoy the sea thanks to his savings. To enjoy the sea more in the sense of health rather than in the sense of luxury.

Of course this left some kind of mark on our desire to travel, but however, the opportunities at that time were very limited, in the financial sense but also in the sense of the freedom of movement. What else do I remember? Or something that is…I remember that my father was the one who bought one of the first cars in Gjilan. He bought a car in 1967. A car with which we travelled to Ulcinj at that time, through Qakorr, a very difficult mountain road which hasn’t been asphalted to this day. But in 1968, we also travelled to Turkey, Izmir, even that road was very difficult at that time because of bad infrastructure.

Aurela Kadriu: You went to Izmir by car?

Ilir Gjinolli: Yes. In 1968. Of course, we took a break in Istanbul.

Aurela Kadriu: Do you remember this experience?

Ilir Gjinolli: I remember that it was a long journey, we spent around a week in Varna, Bulgaria if I am not mistaken. Then we went to Istanbul from Varna. My mother’s cousins who had moved in the ‘50s were living in Istanbul. I remember that we stayed there for four or five days and…then we went to Izmir. Izmir was around 900 kilometers from Istanbul, we went there to my father’s paternal uncles, who also moved to Turkey in the ‘50s. I remember that on the way we also stopped in Edirne and visited the mosque of Edirne, it is a big mosque about which I later learned in the faculty, the Mosque of Sultan Selim. Until that time, or until recently it was the biggest mosque, but also now it has the biggest dome among all the mosques in the world. I mean, we are speaking about the 16th century, it is a work of architect Sinan, Mimar Sinan.

Aurela Kadriu: What kind of city was Istanbul?

Ilir Gjinolli: I remember very little from Istanbul. I only remember the Galata bridge, and I remember when we went, this was in Bursa if I am not mistaken, or in Istanbul, I don’t know, crossing the sea by a boat which wasn’t suitable for cars, but as Turks improvise, they had improvised even in this. And we took the risk because otherwise we would miss the ferryboat and in order not to wait for long, we took a boat.

I have returned to Istanbul many times after that, but I remember very little from that time because I was six, but I will always remember the Galata bridge.

Aurela Kadriu: Why do you think that the bridge is an persisting memory of yours?

Ilir Gjinolli: Somehow the bridge was a meeting point for everyone, and that is where the closed çarshia end, the Kapalıçarşı [Grand Bazaar], Masar çarşı end at Galata bridge, there is also the new Mosque, or Jeni Cami. There is a station from which you can go to the side of Karaköy and Bernoulli and on the other side there is Beyazit and Aksaray. I mean, the part where those who went from Kosovo and other Balkan countries usually settled.

So I guess this is why I remember Galata. But it was also the only existing bridge at that time because Bosphorus bridge didn’t exist at that time. The Bosphorus bridge was built in ’72, there was no other bridge upon the Golden Horn or as they call it Haliç in. The Galata bridge was the only one and it was significant because it could open in the middle so that the ship could pass through and get to the other side. I mean, maybe it is because of the story of the bridge that opens and closes why I remember it.

Aurela Kadriu: In which year did you go to gymnasium?

Ilir Gjinolli: Gymnasium? I started gymnasium in 1976 and finished in 1980.

Aurela Kadriu: How was that for you, how do you remember gymnasium?

Ilir Gjinolli: Back then the first grade of gymnasium was general, I mean, you would enroll as a student who couldn’t choose a department, you could only do that in the second year. One would either pick the natural sciences, where exact science dominated, or the social sciences where social sciences and languages dominated mostly. I went as an excellent student from the elementary school and got in without having to take the admission exams. Otherwise, students with lower grades had to take the admission exams.

I remember gymnasium, I remember a lot from that time. The school building was new when I enrolled, the Zenel Hajdini Gymnasium was opened in 1974…

Aurela Kadriu: Did it have the same name?

Ilir Gjinolli: Yes. I mean, I came to the gymnasium three years after [it was built] and it was something rare. The teaching was done in dedicated cabinets for every subject, they were equipped with teaching tools for every subject. For example, we had the cabinet of biology, chemistry, physics, technical drawing, where there was also the photography club. Then we had the cabinet of linguistics such as English, Latin and French, whoever wanted to learn French, of course. Teaching was done that way that we moved from one cabinet to the other, we didn’t have a classroom of our own until the third year if I am not mistaken, this stopped right after the first year.

But however, the school was still new and we especially were happy for the fact that we had a hall for the class of physical education which we didn’t have at the elementary school. And the days when we had physical education classes were special, we always couldn’t wait for them, because we wanted to play with friends. Of course, we couldn’t always play because there were some exercises which we didn’t like all that much, but however, it was a way to get out of the routine of sitting and listening.

Most of the teachers we had, influenced my education. For example, my class monitor who was also my technical drawing teacher, he wanted us to write and draw beautifully, he taught us photography. He made it possible for us to use the tools of the photography club in order to learn to take photographs with friends or personal ones and so on. I mean, it was an experience which wasn’t accessible for everyone.

Then there is my late physics teacher who taught us physics in a way that I still remember, I think the way he organized the class was unique. It was unique for the gymnasium and maybe for the whole Kosovo, because he tried to involve everyone in the process and ask and…I mean, he made questions that weren’t necessarily going to be graded, so it was a stress-free process. I mean, we could always give our answers in a relaxed way in order to learn the essence of physics and not learn what is how to say, very theoretical and hard to understand if not illustrated in practice. All I learned from physics, I applied in faculty, of course always connecting it with the physics that we learn in architecture such as mechanics or construction physics and so on and so on.

Our English language teacher was also good and of course, whoever wanted to learn English could learn it from him. Most of what I know from English in the systemic sense, that is, grammar and syntax, I have learned in gymnasium. I never took English language courses, but today I can speak and write without any problem. I always worked and written in English until my Ph.D. As far as the systemic sense of a language goes, I have learned all that in school. A bit in the elementary school, to be honest, but most of it in high school.

Same with the Albanian language teacher who insisted on us learning the language. To learn writing and speaking the standard language without any mistakes, but also literature…He also taught us literature which was often, for that time, not to say forbidden, but always discussible whether it was appropriate for children or not. I mean, most of the professors that we had were professors who influenced my further development.

Aurela Kadriu: What do you remember from your friendships?

Ilir Gjinolli: From friendships, my classmates were really close to each other, we always used birthdays or trips in nature to get along and create relations. And maybe it wasn’t very common at that time, but we had a mixed friendship, not only men, but also women. Of course, in a city like Gjilan which was way smaller than it is now, and in a different historical context, the ‘70s…It was different for men and women to hang out together, especially after school hours.

Even though going out to coffee shops back then was a really rare thing, but we would hang out at home or eventually go to the cinema or a party that was organized at school. For example the disco club, for some time we would go every Saturday, back at that time we also had school on Saturdays, it was a workday. I remember that we had the disco club on Saturday evening. Besides the disco club, there were of course poetry evenings, we had sports tournaments in soccer and basketball…And these all contributed to us getting closer to each other. With some of the friends we meet more often and of course this has to do with the number, because you cannot gather a big group of people together.

But in general, all of us were really comic and I guess it was because of our class monitor, who was very supportive, I mean, he asked us for discipline but he was always supportive of every kind of activity that we asked him or encouraged him to join us…So, he was a kind of friend to us. We still keep the friendship with our class monitor.

I told you our annual routine, when our friends who live abroad come to Kosovo for vacation, we always gather one summer evening to remember those times. Even though the situation has changed now, most of the friends have been qualified in different professions, but what we talk mostly about is the past, we remember the friendship and so on. Other? [Addresses the interviewer]

Aurela Kadriu: I am interested, somehow in high school one is more conscious of what they see, what surrounds them. Did you have a tendency to experience the city in a certain way from high school? How was Gjilan, how do you remember it?

Ilir Gjinolli: The road from home to school took me at least 20-25 minutes. I mean, I would start school at 7AM, that is, I had to wake up early. And it was always a routine which I still keep going with my children, first we had to have breakfast then leave home. As a child, one doesn’t like it that much but then one gets used to it and it is good because you create a food order, you know that you should eat three times a day and like that you are physically and mentally able to follow the lessons.

Walking to school took me maybe twenty minutes because I had to walk quickly and in the morning, usually the city was moving because every job in the public sector would start at 7AM back then. But going back from school would always take longer because I wasn’t in a rush to get home so we would talk and stop where the streets with friends would be divided, one would leave in the first street, the other in the second, in the end, I would always remain alone for ten or more minutes.

I experienced or learned about the city through walking. Some buildings were there during that time, some came in the meantime. I always wanted to go to movies, even when I was little but especially during gymnasium. I mean, we wouldn’t miss almost any movie. We were, besides playing we also were soccer fans, but especially handball fans when the Gjilan’s Božur competed in the second league of former Yugoslavia. I remember that I also made a flag in order to be in the middle of the fans.

Usually the matches were on Sundays, I mean, they barely were organized on Saturdays, mainly on Sundays. We would go to a handball match early during the day, the matches would usually take place at 10AM, or later, depending on the season, and then at 2PM or 4PM we would go to watch soccer, later on also basketball. When I started playing basketball more actively, we would also go to basketball matches, even in other cities of Kosovo.

Aurela Kadriu: Were you part of any basketball team or did you just play for fun?

Ilir Gjinolli: No, I played basketball, we mainly played basketball with friends in the gymnasium but also near the school where I finished elementary school. We would always gather in the evening when students would finish school and it was a good atmosphere. For some time I played for the juniors of the team of Gjilan but then…this was when I was in the fourth year of gymnasium so when I completed school, it was the time to go to university. Before going to university, the system changed and we had to go to military service in the Yugoslav Army. So, I went to the military service right after gymnasium, I continued my studies when I came back.

Aurela Kadriu: Where did you do military service?

Ilir Gjinolli: I did it in Požarevac, a city in the northeast of Serbia, 90 kilometers from Belgrade. Otherwise, it is also the birthplace of Slobodan Milošević. I remember almost everything from that time, I especially remember the movies that I watched during that time because the goal of the soldiers is to get out of the barracks to the city, and the other goal is to go home on vacations.

Usually when we would go out, there were two cinemas in the city, they all screened movies that were new, back then all the new movies…The circulation of movies wasn’t like today, I mean, new movies would usually come from festivals, the Belgrade festival was how to say, like a collection of all the best movies in the world. First they were screened in Belgrade, then they would go to other places. Since Požarevac was near Belgrade, it means that movies which we heard about would come to Požarevac, and of course when we would go to watch them when we knew they were coming.

The Hair is one of the movies that I remember from military service, it is by Milos Forman, I don’t know if you have… [Addresses the interviewer]. That’s just one of them because there are so many movies that I cannot remember right now, but honestly movies were what kept my mood in military service because it was really…When I went to the military service, I weighed only 53 kilograms, and the exercises that we had to do weren’t all that difficult but it was something that was repeated every day and it simply was a routine that transformed into monotony.

Then impossibility of communicating with the family when you wanted was very problematic for someone as young as I was at that time, I was 18. It was also the fear, the fear of a new setting, new people, people from all around, from every category, there were people from deep villages of let’s say, Bosnia, who had no knowledge at all, and then there were those from Belgrade for example who were of course in a higher level than us, because of the development of Belgrade. I mean, a mixed society from which you were often afraid or how to say, hesitant to create friendships. I mean, there was always the group of people who were closer, for example Albanians, or maybe a Serb, or someone else who is from your country, who is closer to you.

Aurela Kadriu: What kind of cinema did Gjilan have? You also mentioned it earlier…

Ilir Gjinolli: The cinema of Gjilan was in the city center, now it is the city theater. Back then it was both, a theater and a cinema, it was the culture house, when they wanted to screen movies they would lower the curtains and when there were plays, they would be raised. It was the amateur theater of Gjilan but it always had good plays. They are still remembered.

Aurela Kadriu: What was its name at that time?

Ilir Gjinolli: The house of culture, I don’t remember whether it has a name or not. We only referred to it as the cinema or the theater, but it was the same location. But usually there was the cinema, how to say, one movie was screened on three schedules, on Sunday there were movies starting at 10PM, then on Saturday there were movies that were screened at 3PM. Usually it was…In fact, there were two schedules, one at 5PM the other at 7PM, on Saturdays sometimes there were movies that started at 3PM. But it depended on the movies, how to say one movie came…I mean, there were three movies within one week and we knew when the next movie was coming, that is, you could plan the day. For example, this was different from Pristina because here the movies in three cinemas were screened only within one week. I mean, you had one week to watch the movie in one of the cinemas. Cinema Vllaznimi [Brotherhood], Cinema Rinia [Youth] and Cinema APJ [Yugoslav National Army]. In fact, there were four halls, Cinema Rinia had two halls, the big and the small one.

In Gjilan, there was a movie every second or maximum every third day. I guess it was because of the audience. But then there were movies for which there was a lot of interest and they lasted longer. I remember that there was a kind of festival of movies from Albania, there were around ten movies that were part of it and the hall was always full. What I also remember is that there was a lot of surveillance from the Secretariat of Internal Affairs of who was watching the movies, even though there were many people [going to the movies]. The Indian movies were very famous and very visited, there were many people going to watch them, then there were Turkish movies. I could never understand why they were attracted by the Indian and Turkish movies more than with let’s say, American or French movies.