…dedem Türkçe konuşurdu ve o dilde eğitim gördü, Türk spor salonundaydı, dili Üsküp’te öğrendi, çok zeki yaşlı bir adamdı. O aileden iki erkek kardeşi vardı, biri çiftçilikle uğraşıyordu, sadece çiftçilikle, diğeri hayvancılıkla uğraşıyordu, çünkü o zamanlar o tezgahlar yerdeydi ve onlar da sadece bu işlerle uğraşıyordu, kışlık odun alıp evin diğer ihtiyaçlarını gideriyordu, dedem sadece tören kıyafetleri giyerdi, siyah beyaz renkte bir čakširima, mokasenler ve her zaman ayinlerde orada olurdu. […] Dedemin bildiğini, sana sadece bir anekdot anlatacağım, üzgünüm bunu o ölmeden bir süre önce yazamadım, 89’da öldüğünde, onun… 19 yıl sonra, son 19 yılda, pardon, 88’inde bir yerde, kör oldu, 19 yıldır kördü, babam felçliydi, bir anda felç olmuştu ve büyükannem kanepede oturuyordu, {önde gösteriyor} diğer kanepede de dedem oturuyordu, üzüntüden bir kilo kahve çekirdeği aldı ve sağ elinin yanındaki kanepede bir kilo kahvede kaç tane çekirdek olduğunu saydı. Bu beş cümleyi niye yazmadığımı asla unutmayacağım ama artık iş işten geçti {ellerini kaldırır}. Sonrasında ise, o kahvede tam olarak kaç tane çekirdek olduğunu biliyordu, bir kilo kahveyi öğütmek için değirmenin kaç kez dönmesi gerektiğini tam olarak biliyordu ve o değirmende tam olarak kaç tane çekirdek olduğunu biliyordu (gülümsüyor).

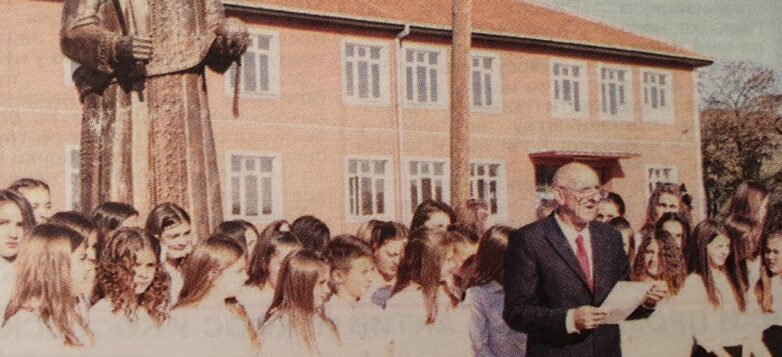

Ljubomir Maksimović 1955 yılında Gračanica’da doğdu. 1977’de Yüksek Pedagoji Okulu’nu bitirdi. 1980 yılında Klina’da öğretmenlik yaptı. Daha sonra Graçanica’da kitapçı müdürü olarak çalıştı ve on yıl orada kaldı. 1996-2005 yılları arasında Priştine Belediyesi’nde belediye memuru olarak çalıştı. Bugün, Bay Maksimović Graçanica’daki Kralj Milutin İlköğretim Okulu’nda öğretmen olarak çalışıyor ve ailesiyle birlikte orada yaşıyor.