Part Three

Anita Susuri: Mr. Ilaz, you were telling us earlier about your release from prison and how you continued life in 1979 and 1980, that is. Were you employed?

Ilaz Pireva: In 1981 I was employed at the Faculty of Medicine. I travelled every day from Prishtina to here, that is, to Lupç. I had, I had a particular approach with the students of the Faculty of Medicine, starting with Shqiptari [Demaçi]. I kept a little distance from some activists who were present. I had some cooperation with them. Few people knew who I was, and I guided, little by little, those student leaders who enjoyed a certain regard. Until the 1990s, when we were dismissed. Then, again, when the faculty reopened, I worked then in the student administration, and at that time I was also chairman of the LDK in Podujeva…

Anita Susuri: After the war?

Ilaz Pireva: No, no, in 1993, in 1993. But continuously I worked at the Faculty of Medicine in administration. There, work was done to create as good an environment as possible for the students, for their studies. Because if a faculty can be completed even in those circumstances, medicine does not tolerate improvisation. To complete medical studies without laboratories, without institutions, without everything a medical student needs, can only be a deception. But thanks to the great will they had, they managed to show that when they later went to other places for specialization, they demonstrated success. That is a truth that should not be forgotten.

The Faculty of Medicine always had it somewhat easier with its own children. Because they were selected students from all of Kosovo, and not only from all of Kosovo. It was an ambition: to become a doctor, at that time the only profession that could allow one to live somewhat at the level required, to raise children and to live a bit. But on the other hand, being a doctor is a very great responsibility. Still, they selected the best students. Competition was such that out of 1000 candidates, 150 were accepted. Almost every seventh or eighth was rejected, all excellent pupils.

Thus, even that period was relatively well endured by the Faculty of Medicine, thanks also to the teaching staff, their commitment, and also the students. Thus, with the return to where the student belongs, in the amphitheatre, in the laboratory, at the bedside of the patient, only then can what is sought be achieved. But unfortunately, we all expected that we would revive a bit faster and better. Again there were difficulties, again… do not forget, the criteria for enrolling in the Faculty of Medicine were very strict. Even under those house-school conditions, schooling was preserved. Later, that level somewhat declined.

Thus later I served two mandates as a deputy of the Assembly of Kosovo. I will not mention the mandate from 1992 to 1998, when the Assembly of Kosovo could not be constituted. In 2007 I ran and was elected Mayor of the Municipality of Podujeva. It was the first mandate in which the mayor was elected by direct vote of the citizen. Until then, mayors were elected by Municipal Assemblies. I made efforts, bearing in mind the very difficult post-war situation. First, I promised the citizens that you will not have deceit; you know that possibilities are limited even for a mayor. As much as possible will be done.

I said, do not burden me through my children and my circle with various matters, let my hand reach where the need is greatest. I had the understanding of my family and my circle, and honestly I believe I did not fall into any trap of greed, neither from family members nor from my circle. Now citizens often tell me, “You helped me here,” even though you do not have many possibilities to help. Thus I consider that I parted satisfied; even today people tell me this, people I do not know, I do not know who they are.

I returned later and worked as an advisor to the president for several months. When President Fatmir Sejdiu resigned, that was also when the retirement age came. I retired with 75 euros. Later, thanks to the law passed in the Assembly that recognized prison time as work service, I managed to have my pension now at around 260–270 euros. With the money from prison and with the help of my family, I built this house. I have a daughter there in London. She was the initiator to begin then…

Anita Susuri: I wanted to ask a bit about your family, about how you met your wife. How did you marry, and did she have to wait for you while you were in prison?

Ilaz Pireva: To tell you the truth, my marriage, on July 16, will mark 62 years. That is, my mother and father married me in the traditional way as it was done then. In that respect, as a traditional family we were, even when I was in the Prison of Sremska Mitrovica, I met other prisoners, Serbs, Montenegrins, and Russians. We talked. They knew that it was my second time in prison, they knew I was married.

They asked me, “How can you endure life in this way?” At that time I had three daughters, in 1975. One of them I had left at one year and something. I said, “I am not worried, I live in a family household with my father,” I also had my uncle, “with brothers, with my uncle’s sons. I do not even think whether the children have bread, because as much as we have, they have as well. They have all the conditions. They are even more privileged than other children.” “Oh,” he said, “for you it must be easy to endure prison.”

They also asked me something else, since they too were imprisoned for the second time, an issue worth mentioning. “We are interested,” he said, “how did your surroundings receive you when you returned from your first imprisonment?” I said, “For a month the door of the men’s chamber was open,” I said, “people came to visit me and welcome me and say other words that are said to someone returning from prison.” “Oh,” he said, “but you know why you are in prison. Us,” since they had also been imprisoned before, “not only did no one visit us, but even our closest relatives did not speak to us. We were ignored.” All of them were separated from their wives, meaning broken families.

Anita Susuri: Were they political prisoners?

Ilaz Pireva: Yes, yes, political. It was about politics. Some had fallen in 1948 for entering some kind of bureau and were imprisoned, then for the second time in the 1970s they were imprisoned again. And now when I told them how it was with family. “You know why you are imprisoned, but we were destroyed and society did not accept us when we returned from prison.” I say, all of them had been separated from their wives.

Only one, I say, had a devoted wife. She even had another profession. She went and trained as a nurse, because he was ill, to help her husband. Only this one, a Morača, his family was well known in the Second World War and had many generals. And his wife, from Vojvodina there, retrained as a nurse to help her husband. Later the husband died in prison.

Thus with all of us, I mentioned my case, but it was like that with everyone. I had a sick wife; she underwent surgery and no one believed she would survive. Then some of her friends would come like this, and I would serve them. Like I served you a glass of water. They would say to me, “Blessed are you for such merit.” I would say, “Oh, my wife says you have no merit, only may God forgive the debts.” She never said that to me, but I would say it to them as if she said it: “Only may God forgive the debts.” That is the reality, look at it directly, that is how it is. If we can, to have our debts forgiven.

Anita Susuri: I am also interested in whether you have any memories from prison in Sremska Mitrovica, especially to speak a bit about visits and how difficult it was for your family to come all the way there to visit you.

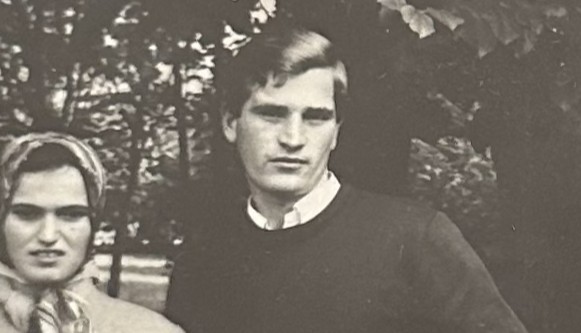

Ilaz Pireva: In the Niš Prison, when I was in Niš, this daughter of mine, Afërdita, was born. So the children didn’t… in Mitrovica they came to see me… here they didn’t allow my children to see me at all. I spent a year in Mitrovica and they never allowed the children to come. Here, after six months. There, yes. I had a photograph of myself in the room. When all three daughters came to visit me, they arrived with the image they had seen in that photograph, with that picture in their minds.

When they came and saw another man, with the clothes of a prisoner, they said, “This is not our father.” So it was not easy, you know, for a child to say, “This is not my father,” because they had their father in front of them, in that portrait in the room. It’s not an easy experience. But one thing must be understood: in time we learned that first you place yourself, and then, once you are prepared in yourself, you can also sacrifice others in a way – your wife, your mother and father, your children. How right that is is another question, but you do that consciously.

I, especially, had great support from my family. In that respect I did not have… there was no, “What happened? Why did we end up like this?” because life was not very easy. Those are the consequences… later my brother was driven out, for a year – no, not for a year, he spent ten years unemployed because of me, that is. Not to mention the other consequences. But I will tell you something from the heart: all these things that happened to us, their head was in Belgrade, and that is easier to bear. What can you do when the head is in our own place. That cannot be swallowed. Because when it comes from your historic enemy over there, we have nothing more to say.

So, the other day I saw the interview with Shqiptar [Demaçi]. He said, “They didn’t obstruct me during my schooling. Serbia is smart; she deals with big matters, not with these.” Meaning, they didn’t interrupt him, they didn’t tell Demaçi, this Shqiptar, “You’ve lost the right to study.” “No, no, go on, you study, we’ll work on something else.” That’s why Serbia has a clever policy – strong, low, everything. And so we can say the family was preserved. The family was preserved.

Anita Susuri: How often did you have visits?

Ilaz Pireva: Once a month. We had visits once a month. Fifteen minutes. The interpreter was right over your head, so to speak – you were allowed to talk only about family matters, nothing else. Letters, the same, once a month you could send one: “I’m fine, may you be well.” You couldn’t say anything else… Sremska Mitrovica was the first time… when they sent me there, they sent me with a Serb and a Montenegrin. That Serb was actually from Prishtina, his father had been director of the theatre in Prishtina, and he too was there for political reasons. They had wanted to form new communist parties, not the one that already existed. A very sharp young man. The prison guards’ commander told them, “I’ll bring you a compatriot of yours, with whom you won’t be able to cope.”

I could see they were paying extraordinary attention to me. They were very cautious with me in every way. Because he had said, “He’s a bit…” you know. They watched me closely in everything. After a month… Montenegrin, more than him, he was more prepared. “Ilaz,” he said, “we have to tell you: this and this. That commander of the guards threatened us he would bring us a compatriot of yours,” because they had refused to work. “But you’ve shown completely correct, normal behaviour in everything.” Then we started talking. I explained the issue of ‘68 as well, because they had interpreted it completely differently from the way we interpret it here.

We started… later others came, new people came, in other rooms there were also prisoners there. We had a kind of debate; for the first time I had a conversation and harsh polemics with Serbs. They were so unreasonable that in ‘81 you might have thought they had come out of prison and taken power. Then I began to read those Belgrade newspapers, what they were writing, you know, with politics, with interviews, with Danas and all the rest of that cursed press. I think the conversations I had with them back then, now you have them in newspapers and on television. It’s the same logic. And when they sometimes say, “The Chetniks, the Chetniks,” there is no Chetnik and Partisan, they are one and the same. There, in that prison, in a way we were isolated…

Anita Susuri: Did you have walks?

Ilaz Pireva: Walks yes, we had walks. It was a prison where foreigners had also served time, international prisoners had been held there. You had to prepare yourself for the treatment, so they couldn’t lead you into some traps. Because they make certain preparations that… so that you must, as we said earlier, come out of prison with as few consequences as possible. Because in prison you can’t really do anything, in the end. So that also passed. But we were fully aware that… once, back in ‘75, I had told a State Security investigator, I said, “I thought I had finished my prison then,” for ‘68, “and that I had become like all other citizens.”

“No, man, you will never be like the other citizens,” he said. “Fifty years after you die, only then will a line be drawn over your name and over the others’.” And the truth is, reality was like that.

As I said, in ‘74 there was that overthrow in Chile, Allende was toppled. Some Pinochet, they later caught him at the end of the 2000s, or ‘90s, the generals detained him. That socialist system of Allende’s. They filled the stadiums with arrested people because they had no other place. They committed terror and killings. I had said to them, you know, “You are acting like in Chile there.” Then he said, that security man told me, “Remember one thing: the police here, in Chile there, in China, in America, and in that Albania you love, the police is the police,” and it turns out the police is the police (laughs).

Anita Susuri: I’m interested now also in ‘89, which you mentioned, when they took you again and you were subjected to those tortures. How bad was it… you said there were around 200 people.

Ilaz Pireva: More than 200, yes over 200, there is also a book about that, it’s called Izolantët [The Isolated]. Those of us they sent to Serbia, that is, to Vranje they had sent us, to Leskovac, to Valjevo, to Prokuplje, then Zaječar, Belgrade. They filled… but it’s interesting to stress that in ‘89 the overwhelming majority of those detained were not former political prisoners, but leading cadres in enterprises. Because back then, as I told you, in ‘68 there had been a debate about advancing the status of the province, and in ‘89 there was a debate about some constitutional changes.

Those debates were developed also in work collectives. And there, whoever had stood out a bit more among directors, chiefs… from all the major enterprises in Kosovo there were people, the leading figures of those social enterprises that existed then, and some other figures as I said. I was sitting with – he had been my professor – Rexhep Ismajli, and another former political prisoner. Now whom fate touched I don’t know, you know, but me, I was always there…

Anita Susuri: Did it also happen as an arrest, or how?

Ilaz Pireva: No, they don’t say “arrest,” they just threaten you, that you are one of those and so on. Then they issue a decision, just “change of place of residence,” nothing more. Then for some they extended it, and later, based on the investigations that were developed somewhere, they even sentenced them, that is. But the vast majority were released after five–six months. We were released after two months. When they had tortured us so severely, someone – some voice – reached Belgrade, and they came from Belgrade and saw the condition we were in.

Then they took us, tried with some medicines, some ointments, to smear our bodies, which were covered in wounds. Then they dispersed us to other places, you know. And then they opened, supposedly, a case against the director of the Leskovac Prison. We had even received summons to go to that trial. I said, “No, I’m not going.” And do you know what his response was, when they asked him, “Why did you torture them to such an extent?” He said, “That’s how they brought them to us from Prishtina, in that condition.” So that was his justification. “We didn’t touch them with a finger, God forbid, but this is how they arrived from Prishtina.”

Anita Susuri: Was he sentenced to anything?

Ilaz Pireva: Hm?

Anita Susuri: Was he punished at all?

Ilaz Pireva: Three months suspended, or I don’t know. Just, you know, a formality, because they came from… at that time Vrhovec, a Croat, was foreign minister. A certain Drnovšek was president of Yugoslavia then, with that rotating presidency.

Anita Susuri: Did any organizations intervene, like Amnesty International and such?

Ilaz Pireva: Those above all, let’s say, from that centre. The very fact that they came from Belgrade and saw the situation – now we can suppose maybe it was at someone’s initiative, we cannot know. But rather, considering that things had gone a bit too far, what happened in Leskovac had gone beyond limits. Now, from whom… but what was, let’s say, good in this case, is that someone of ours has said, “We left them in the worst condition, those we sent to Leskovac.” Then he added something somewhere. Now how it all evolved, I cannot say.

Anita Susuri: Could you now describe the road and what you were thinking would happen to you? Or did you not know where you were going?

Ilaz Pireva: In those situations you do not think about anything at all. Nothing, to tell you the truth. Because for me, again, all of this seems small compared to what happened in ‘99 in Dubrava. So like for many others… Once someone asked me, “Why did you not take some photos or recordings of the burned house?” Leave those things. Where the burned house is mentioned, or where so many other things are mentioned.

So, when you think again about what happened to so many others, you say no, do not, it even makes me want to say sometimes that maybe we are overdoing it a bit, you know. Because, let me tell you something honestly, there are many fighters, many activists who did their work and you never heard their voice. Some others do it with a bit more noise, a bit more here and there. Therefore, we must be careful here. We must be careful here.

Anita Susuri: Then you said after two months you returned home…

Ilaz Pireva: Yes.

Anita Susuri: And then came the nineties. You mentioned the Reconciliation of Blood Feuds, did you also take part?

Ilaz Pireva: Yes, I took part in it as well. I did, but I was not an official part of it, more as an activist, as a name that I had at that time, you know, in that sense. But I followed it, I was also in Bubavec when a big gathering was held, and at the Verat e Llukës, where half a million people is mentioned. And in this area here, and not only then but also later, I contributed to bringing many families closer together.

So I can say that I tried, within my possibilities, because there is always room and space to work in a good and right way. Even when I was a deputy in the Assembly of Kosovo, some of those who until yesterday were with us but were now lined up on the other side would say to me, “Come here, this is where you belong, come here, over there…” I would say, “If these are bad, I will try to make them good as well.” So I was not burdened with the question whether someone is this or that…

In fact, there was the Parliamentary Party, Zahir was in the Parliamentary Party then in Orllan, and someone comes and tells me, an activist whom I did not know, only that he said he was from the LDK, “Some from the other party have entered into our share, they are collecting the Three Percent.” One of our activists was killed under three tortures because of the three percent. Where am I supposed to find people who go there, whether they belong to the Parliamentary Party or to the LDK… because otherwise, one villager was a social democrat, another something else… For me it was very understandable that everyone should act under the circumstances we had.

So I said, “And what do you want to say with this? Leave those things, where am I supposed to find people,” because to tell you the truth it was not easy to engage people. At the beginning, those letters we had were of great value, for those who were tortured, so that we could give them to those who entered work in the West. At first I hesitated, I thought I might become the cause for separating them from their families. But at some point I became convinced that whoever is a good person, wherever he goes, his hand will reach. But the bad one, you have him neither there nor here nor anywhere.

So also in that aspect, you have to bear in mind the solidarity that existed not only in reconciliation but also in the assistance to the families so that there would be a bite of bread. There was also that “Family helps family”, and that gave a great contribution. Many families supported other families, every month they sent them as much as they could within that standard of need. So it was a field where you could act, work.

And once they tortured me, they took me several times here as well, for so-called informative talks, the Serbian police. They came here two or three times and searched my house. We had begun to build a school here in Majac, I had its project and everything, construction had started vigorously, they came and interrupted us. They came, took the project from me, summoned me and threatened me. “You know this is a military secret, the school project.” That is how they had it. Because in wartime they turn the school into an object for their own needs. Now you have supposedly taken the secret. Just as once they tortured us, they laid us on the ground when one of their security men was killed. That security man was Albanian, he was killed.

Anita Susuri: The nineties?

Ilaz Pireva: Around ’95 somewhere there. As chairman, and together with seven other members of the presidency, but I felt it easier because believe me, there was no day on which activists were not taken and beaten in police stations. So I shared that fate also in this period, even though I already had some years and some troubles. But again with these young ones I shared a fate with them. So, it was all right.

[Here the interview is interrupted for technical reasons]

Anita Susuri: Are you ready?

Ilaz Pireva: Yes, yes, I am ready.

Anita Susuri: I think you wanted to say something…

Ilaz Pireva: The secretary of the branch was the commander of the territorial defense for the operational zone of Llap. I sent him word, in fact, because I knew him, not that I knew him personally, but I knew one of his relatives. I sent word, he had this man as his son-in-law. “Tell Muhamet that you no longer have a place here, go higher.” He comes and says, I do not know if the message had reached him. But this one comes and says so and so, “I intend…” “May it go well for you, just one piece of advice, bring people closer. You are fighters of freedom, there is no ‘this one belongs to this group, that one to that group,’ you are all one.” “Honestly I did not know this,” he said. “I have heard some words,” I said, “therefore I am just advising you too.”

Later when I met him he said, “There had been something, but we have overcome it.” So we have overcome also those differences that could have occurred. We secured flour from the traders of Llap, they bought it wholesale by trucks from Serbia and we sent it as far as Leposaviq through Shala e Bajgorës. It even reached the point where that trader trusted me with credit because we did not have the money right away, so we took care. And in another situation I had my daughter engaged, and this is like a crime you know, but… her dowry, all that she had prepared as a bride, with blankets, with all those quilts and things, we sent it. I wanted just as a symbol, you know.

We organized… the citizens expressed it at once, and I said, “Just do not rush, do not spend everything on me at the first step, because we do not know how long this will last.” So also in that aspect work was done, and above all for bringing people closer, for care, for… then I also worked at the Faculty of Medicine. There was the headquarters as well… the dean, he is in the other world now, Hashim Aliu, there where… they drew up the schedule of all the doctors who were to go out into the field. The doctors did not spare anything. Some of them even stayed there until the war ended and could not return to Prishtina. So in all pores, in all segments of life, we tried and worked. As for the others I cannot speak.

Anita Susuri: You were here during the war, right?

Ilaz Pireva: Yes. I was in Pristina; in fact a certain activist died here, who I had even closer than just as an activist. I stopped there at the crossroads, the Serbian police were there. When they saw that my ID card was from Lupç, they immediately, “Kako ti je UÇK, kako ti je… [Serbian: How is your UÇK, how is your…]” you know, “how is it, how is…” I saw that I could no longer… and I stayed in the Muhaxherët neighborhood at my sister’s house until April 4, 1999. On April 4 we went to the border there at Hani i Elezit in Bllace. We stayed two days, but we did not experience that horror that others experienced for a week without stopping in the rain.

I stayed ten days in a camp nearby. They came and told me to go somewhere, I said, “No.” I had planned to go toward Albania. A high NATO officer came, he talked about some things, I also gave him an address of someone he should talk to, I told him some things which, unfortunately, turned out exactly as I had said. Because he was a high military officer of NATO, but a Frenchman. I mean the role of France, which it has had in what Serbia is today.

From there I went to Tetova, from Tetova again with some connections I went to Dibra intending to go to Albania. But I saw that I had no place, so to say. And immediately after that I came back. I started working again here…

Anita Susuri: In what condition did you find the place when you returned? You said your house had been burned as well?

Ilaz Pireva: Yes, yes, starting from my house they burned another six or seven houses in the neighborhood. So, as I said, I lived for some years in Prishtina in rented accommodation. When I later came to run for mayor, toward the end I moved back here. As I said, I then somehow built the house and now I live in Lower Lupç, not “low” (laughs).

Anita Susuri: You said now you are retired…

Ilaz Pireva: Retired, yes, and for quite a long time. For quite a long time. But now that solidarity of our traditional family still functions. Now, with you young women and with my daughters… we have extended the circle so that even if someone is a bit distant in line, now they say “bring the circle closer, bring the circle closer, bring it closer.” Now I remembered when we approved the law on the definition, the delimitation of what a close family is. Do you know what we get as “narrow family”? Partner, partner, wife, husband, mother, father, child. Not the brother, not the sister, let alone the uncles and others…

I even pointed it out there, I said, “Remove this ‘partner, partner’ from here,” they had put it before wife, before husband. I said, “It is a matter of translation,” as there were many bad translations… so we used to have quite a broad definition of family. I grew up with six paternal aunts; I was raised in their laps. Not with sisters, but with paternal aunts. We also had some other old women who had no one, because their kin had gone to Turkey. We took them in. Because at that time the custom here was that twice a year the daughters had to visit their parents. We took also those others. Not only the paternal aunts, because they had no one… and those were distant relatives.

Now, the daughter Afërdita’s side says to me, “That time has passed.” Now they say you must focus on the close, close, close. I said, no, broaden it, broaden it, broaden it. One last thing as a conclusion, because when people write, not only now but even before, many say something I do not agree with, when they say, “I would not remove a comma, a dot from my life.” I would remove many commas, many dots, many words, many sentences, many periods, many pages, if I could remove them. Thank God, I do not regret those things, but there are other things, and if I had the scissors in my hand now, I would cut out a lot. So I do not agree with those who say, “I would not remove a comma from my life.” No, honestly, I would, but they cannot be removed.

Anita Susuri: All right, Mr. Ilaz, thank you very much for the interview, for your time!

Ilaz Pireva: I do not know how sincere I was, you know that I was, how far I managed to clarify things, that is another matter.

Anita Susuri: Thank you very much!