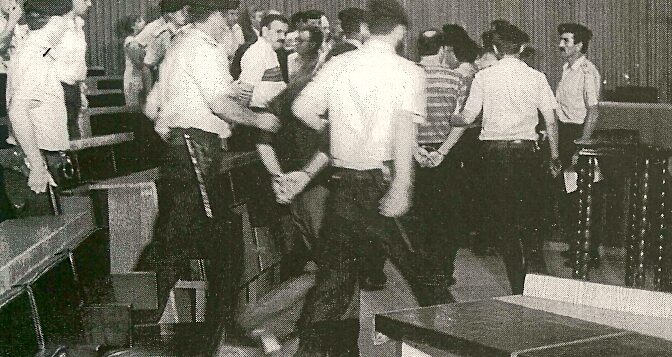

Hakem heyetinde İsmet Emra vardı, başkandı. Panelin bir üyesi kıdemli yargıç Yusuf Mejzini’ydi. O zamanlar çok hasta olan eski bir madenci ve harika bir adam olan Shaban Binaku, Shaban Amca ile sık sık görüşür ve ona yalvarırdık, şimdi kendisi rahmetli oldu, ona yalvarırdık, ‘Lütfen duruşmaya kadar sağlıklı kalın.’ Karadağ’dan bir başka yargıç olan Milutin Zubov vardı ve dengeli bir tavrı vardı. Bu nedenle, nihai kararın dengeleneceğini ve onların [madencilerin] tüm suçlamalardan arınacağını gerçekten umduk ve buna inandık. […] Hırvatistan’da madencileri desteklemek için büyük protestolar oldu. […] Duruşmaya katılan Slovenya, Hırvatistan, Makedonya’dan avukatlar vardı. Bu avukatlar bizimle birlikte madencileri savunuyorlardı. Onlar Doktor Miha’ydı, hayır, Doktor Peter Ceferin, Viyana’da tanıştıkları Miha Kozic’ti. […] Ayrıca, bu adamların serbest bırakılması için hükümetin herhangi bir önerisi olduğuna şahsen inanmıyorum diğer yandan bu adamların cezalandırılması gerektiğine dair bir öneri de kesinlikle yoktu. Neyse ki sonunda madenciler 14 ay gözaltında tutulduktan sonra serbest bırakıldı.

Adem Vokshi 1952 yılında Peja’da doğdu. 1975 yılında Priştine Üniversitesi Hukuk Fakültesi’nden mezun oldu. Mezun olduktan hemen sonra İpek Bölge Mahkemesi’nde staj yaptı. 1978’de ise Mitroviça Bölge Mahkemesi’ne transfer oldu. Bay Vokshi, 1982 yılında bağımsız bir avukat olarak çalışmaya başladı ve 90’lı yıllar boyunca bağımsız olarak çalışmaya devam etti. Şu anda Mitrovica’da yaşıyor ve avukatlık mesleğini Priştine’de sürdürüyor.