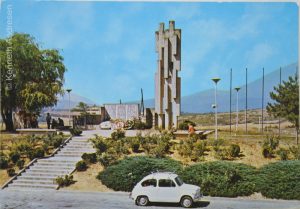

The Boro-Ramiz Memorial, Landovica (Prizren)

The memorial to partisan heroes Boris (Boro) Vukmirović and Ramiz Sadiku in Landovica, a locality a few kilometers from Prizren, was dedicated to Boro, the Regional Committee Secretary of the Communist Party of Yugoslavia in Kosovo, and Ramiz, member of the Bureau of the same Committee, captured and executed in Landovica by the Italian Fascists on April 10, 1943, while they were on their way from Gjakova to Prizren to meet Belgrade’s envoy Svetovar (Tempo) Vukmanović.

The memorial, unveiled in 1963, and built thanks to the lobbying of local government and veterans associations, was designed by Miograd Pecić and Svetomir Arsić –Basara (1928, Sevc, Ferizaj), while the mosaic, depicting the scene of the execution, was by Hilmija Ćatović (Rozaja, 1933-2017).

An Altar to Active Victimhood

Standing alone, the memorial suggests an easy combination of the sacred and profane. The altar-like memorial, with its ten meters tall concrete sculpture, a stylized two-headed figure, suggests a religious devotion, in this case the civil religion of the “active victimhood” of the partisans, in the words of Miranda Jakiša. But it is also used for recreational purposes, as indicated by the men sitting in the corner or the children playing on the landing. And its monumental and abstract sculpture is a symbol of modernity as much as the Fića, popular in 1960s Yugoslavia as a symbol of the newly acquired consumerism. In Kosovo/Kosova (1974, p. 485), we read that the monument was built with the intention to symbolize the pride of the two comrades/friends, whom the Fascists, according to Yugoslav lore, tried unsuccessfully to separate along national lines, offering in vain the Albanian Ramiz to be spared execution.

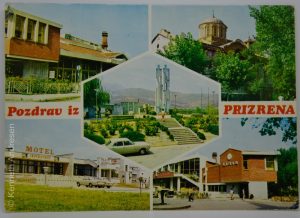

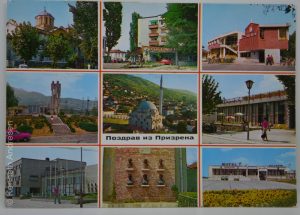

In greeting postcards from Prizren, the Landovica memorial comes to be also a signpost for the city as much as other older, or more urban sites. It is featured at the center of multi-views portraits of the city, with the later-Byzantine, UNESCO protected Serbian Orthodox Church of Sveta Bogorodica Ljeviska, and the seventeenth century Sinan Pasha Mosque, both prominent landmarks. The memorial also appears with the postwar motels and restaurants Vllazrini, Liria, and Sputnik, modern but modest buildings in style and size, in harmony with Prizren’s small scale. Prizren is portrayed in these postcards alternatively as modern or old, or both, but the monument remains a constant signpost.

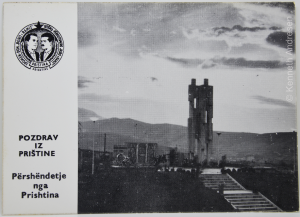

In a black and white postcard, the message is “Greetings from Pristina.” The monument has transcended its location near Prizren to reaffirm the broader symbolism of brotherhood and unity.

One postcard of Prizren views includes the House of Culture, with a memorial to the Second World War, a wall with six busts. This memorial is practically unknown in Kosovo. Built in 1982, at the beginning of the post-Tito political crisis and as demands for a Kosovo Republic were brutally repressed, we can guess that the memorial would be a reaffirmation of the Communist and partisan legacy of the war as the foundation of a unitary Yugoslav state. It has perhaps the shortest life than any other memorial. Shkelzen Maliqi helped recognize some of them: two fallen partisans from Prizren, Xhevdet Doda and Jovanka Radivojević-Kica and perhaps Ganimete Tërbeshi and Emin Duraku, both from Gjakova.

It is impossible to see the Landovica memorial nowadays, because it was destroyed and bulldozed in the recent war, replaced at that location by a cemetery to the fallen of the Kosovo Liberation Army (KLA) in 1998-99. The importance of this replacement did not escape Slobodan Milošević in his cross-examination, at the ICTY, of Halil Morina, a resident of Landovica, who testified on the complete destruction of his village and the killing of score of civilians on March 26, 1999. Milošević denied his army conducted a war against civilians and argued that they were merely fighting the KLA in Landovica. The evidence? The monument to the KLA fallen, built to replace the one to Boro and Ramiz.

The decision to build a KLA memorial cemetery precisely where the old monument once stood is not surprising, as a different symbolism – in this case, the liberation of Kosovo from Serbia – replaced the previous one at a locality which has already been “sacralized” by the presence of a monument to heroes.

As for the Boro and Ramiz memorial, its memory only lives in these old postcards.