Photo by: Alexandre Degrand. In the photo: Waiting for procession in the yard of the cathedral, 1890s. Source: http://www.albanianphotography.net/

Among the classic studies of customary law [Kanun] in the society of the Northern Albanian Ghegs, research conducted by the Catholic clergy is particularly rich for its combination of legal and political analyses as well as ethnographic details. Yet, while the work by the Franciscan Shtjefen Gjeçov [Kanuni i Lekë Dukagjin, first serialized in the magazine Hylli i Dritës in 1913, then published posthumously as a book in 1933], is widely known thanks to translations in several languages, precious material published originally in Italian or Albanian has not had a similar diffusion.

We found a trove of stories dealing with blood feuds and the Kanun in the reports that Jesuit missionaries in northern Albania and Kosovo sent back home to their provincial authorities at the turn of the nineteenth century. These Italian Fathers did not share the nationalist fervor of Gjeçov, who codified the traditional unwritten law focusing on its uniqueness, but did not quite remained detached observers. Deployed in the field, they could neither completely ignore local notions of morality, nor simply denounce their contradictions with religious principles, as did the highest authorities of the Church. Their approach was instead both analytical and practical. They studied and understood the traditional customs of the mountain Albanian tribes, and even when shocked by what they considered unjust or intolerable, they managed to make a pragmatic distinction between what should be abandoned and what could be salvaged in order to make virtuous Catholics of the men of the Kanun.

For those Fathers, two were the most egregious abuses of customary law: the practice of concubinage, and the blood feuds. They dealt with them using all the means at their disposal, including forms of punishments or mediation foreign to their sense of justice: for example, burning the house of the person living with a woman who was not his wife, or resorting to guarantors who might punish violators of besa with murder, inciting further vengeance.

Luckily for us, the Jesuits travelled through the Archdiocese of Skopje and Shkodra, following an old organizational model practiced in distant regions such as the Far East and the Americas, moving from parish to parish in groups of two, the so-called missione volante [literally, flying mission, in the sense of visiting mission]. In the same missionary tradition that produced volumes of observations and analysis of the non-European world during the eighteenth century, they sent lettere edificanti (reports), to the Provincia Veneta of the Compagnia di Gesù, to inform their superiors and the public about their mission in Albania. The authors of the lettere are Father Domenico Pasi, from Verona, Father Francesco Genovizzi, from Bergamo, and Father Angelo Sereggi, an Albanian from Shkodra.

Two books inspired us to translate the stories that the Jesuits sent home: Giuseppe Valentini (ed.), La Legge delle Montagne Albanesi nelle relazioni della missione volante . 1880-1932 [The Law of the Albanian Mountains in the reports of the visiting mission. 1880-1932], Firenze: Leo. S. Olschki Editore, 1969; and Father Fulvio Cordignano, L’Albania a traverso l’opera e gli scritti di un grande Missionario italiano il P. Domenico Pasi S.I. (1847-1914) [Albania in the works and writings of a great Italian Missionary, Father Domenico Pasi S. I.] Vol. II, Roma: Istituto per l’Europa Orientale, 1934. Valentini [1900-1979], trained as a Jesuit, and a former missionary turned professor of Albanian studies at the University of Palermo during the Second World War, is also the author of further studies on the Albanian customary law. Father Cordignano (1887-1952) working in Albania from 1926 to 1941 as a member of the missione volante, became a renowned scholar of Albanian studies.

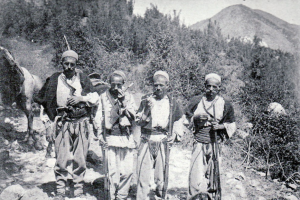

Photo by: Alxandre Degrand. In the photo: Men from Mirdita, 1890s. Source: http://www.albanianphotography.net/

When one is poor, blood money is needed.

January 2, 1893. Dushi.

A widow with children, whose husband had been murdered in a plot involving eight families, would have been persuaded to forgive, but in that case she would not have received a cent from the families of the killers. She too owed blood to someone else in the village, which she could have never reconciled without paying blood money. Thus we thought it was better to wait for the official reconciliation ordered by the Government, which would have happened in a few years, when the widow and her children would have received blood money. In the meantime, we stopped the murders with some besa.

Father Domenico Pasi S.J.

Lettera Edificante della Provincia Veneta della Compagnia di Gesù; Serie V, p. 95.

In: Giuseppe Valentini (ed.), La Legge delle Montagne Albanesi nelle relazioni della missione volante. 1880-1932, Firenze: Leo. S. Olschki Editore, 1969, p. 80.

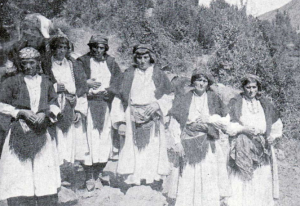

Photo by: Alexandre Degrand. In the Photo: Women from Mirdita, 1890s. Source: http://www.albanianphotography.net/

How it was more difficult to forgive a Turk than a Christian.

1893 – Gomshiqe

They had killed the only two sons of an almost blind and ailing, eighty years old man. He wanted to confess, but without forgiving the killers. One of his nephews, who had led him to me by the hand, and who told me what had happened while helping him kneel, was waiting to see what I would say.

I asked the old man what was his heart’s disposition towards the killers of his children, whether he felt hatred or intended to forgive them. He began a long chat to tell me that the injury he had suffered was too great, that he had nobody, that one of his children didn’t have a Church burial because he lived with a woman who wasn’t his wife, but he was innocent because he lived with her only because his relatives asked him to. In the meantime, he added, he wanted to confess and God would forgive everything.

I tried to convince him to stop hating, otherwise, I said, confession would be useless, or even damaging. He answered, “Yes, yes, I confess.” But I saw that that he did not want to forgive. And thus I clearly said that I could not confess him the way he felt. Then, Giovanni, that was this nephew’s name, said, “You are old, confess, because it would certainly not be you to kill anyone; we will take care of the blood of your children.” I tried again to push Giovanni to forgive and confess, but it was like talking to a deaf, and thus I sent both away, telling them that we would talk about this some other time, because I had to officiate mass, and could not let people wait.

I was told later that his nephew Giovanni too had some trouble with the people from his vllazni [brotherhood], a disagreement, for which he had tried to kill some relatives, but had not succeeded; their enmity was such, that there would not have been any solution without murders, and had that happened, who knows what a series of vengeance would have begun. So they begged me to fix all that mess and obtain a reconciliation, which would have immensely benefited the village, because many families were compromised in that affair.

The last of the five days we spent in Gomshiqe I did try a coup. The church was very crowded, it was all ready for the procession around the church; the banners had been distributed to the four more important people in the village. While we were waiting to start, I talked about the goodness of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, who not only puts up with sinners, but goes looking for them and forgives them, like the good shepherd looks for the lost sheep, like the father in the Gospel forgives the prodigal son. I told them that had they wanted to please Jesus, they had to love each other and sincerely forgive the injuries experienced.

Finally, I invited the young men to forgive each other and also forgive their parents and they immediately cried, “We forgive, we forgive.” Then I addressed the parents and asked them to forgive the disobedience and the unpleasant things their children had done. Then I invited everyone to forgive all possible offense and take all resentment out of their heart, because this was the real way to please the heart of Jesus and dispose him well towards us. The souls of everyone were already well disposed and all cried, “Have mercy on us, Jesus. Mercy. We forgive, we forgive.”

Then I addressed Giovanni, the nephew of the old man whose two sons had been killed and told him, “Giovanni, Jesus is calling you, come closer.” He was surprised by this invitation, and did not know what to do. I called him again and he stood up and came to the middle of the church. Then I said. “Jesus Christ asks you for a grace; you know that the village cannot reach peace if you don’t abandon hatred and sincerely forgive those who have offended you. Well, Jesus Christ is asking for this forgiveness from this cross that I am holding.”

He tried to recuse himself saying that his old uncle had to forgive first, that he had to talk to his relatives and so on. A whisper began to be heard; some pushed him to forgive, relatives and friends said that he could not forgive at that time. Without paying attention to the others, I came closer to Giovanni and told him that he had to kiss the cross I was holding and forgive. He said, “My family is not the first nor the last in the village; there are other families that are richer and larger than mine, and they have bloods to forgive, they should start, the Jakai family, which is the first, should forgive their bloods and then I will forgive mine.”

The head of the Jakai family was a very good young man, he was about 28 years old, Toma or Tomaso, he was good-hearted, well-behaved, religious, and esteemed by everyone. It was he who the previous year had worked hard to have the Jesuit Fathers go and give their blessing in Gomshiqe; he hosted us in his house and helped us for the whole time we were there. I had no idea he had bloods to forgive. He did not wait for me to address him and ask him to forgive; as soon as Giovanni stopped talking, “Yes,” he said, “the Jakai family forgives for the love of Jesus Christ, and does not forgive just any blood, but the blood of a friend, which according to our customs one should never forgive.” Having said that, he came closer and kissed the cross, and called the other members of the family who did the same. Then he called a certain Marco, who had a blood in the village of Dushi for the brother who had been killed four years earlier, and told him to kiss the cross and forgive, and Marco did it.

After Marco, a relative of Giovanni came to kiss the cross, and he was someone who was haunted by Giovanni for a certain injury, as we mentioned. Then it was the turn of Giovanni, who kissed the cross and said he forgave. Only one was left who wanted to take revenge, he was Antonio, who was holding the banner of the Sacred Heart. Two years earlier, while we were in a Mission in Lacci [Laç], some Turks had killed his brother, who was coming back from Scutari [Shkodra], because of a cow that Antonio’s relatives had stolen from the Turks, refusing to give an explanation for it. I had not asked him to forgive, because his case was different from the others and I thought it would be difficult, because he would have to forgive Turks, who do not ask for forgiveness, nor can appreciate the generous, spontaneous forgiveness in the name of Jesus Christ.

But someone whispered in my ears, “Father, only Antonio is left.” Then I addressed him. Without losing his composure, he said, “Father, had I had to forgive Christians, like the others, I would forgive not one, but ten bloods, but the killer of my brother is a Turk and he does not understand forgiveness for the love of Jesus Christ; he would not be grateful, on the contrary, he would feel contempt for me.”

I said that forgiving a Turk for the love of Jesus Christ would have been an act even more worthy than had he forgiven a Christian, he should forgive in the name of his soul, because with that hatred he could not confess, and if he hoped to hurt his brother’s killer, he was hurting certainly himself; he should forgive also in the name of his relatives and the village, which would not be pacified had he not forgiven. I tried to push him to forgive, but he always answered that it was not possible, and that it was useless to ask.

I was already sorry for having put myself in that embarrassing situation, but now giving up would have been worse; thus I continued to insist, and some people helped me begging Antonio to forgive, while others told me to stop asking, because it was useless. Then I decided to untie the knot; I put the cross that was in my hands on the ground and said, “Well, here’s the last attempt I make: here you have Jesus Christ who begs you, not only on the cross, but on the ground, pick it up and kiss it in the name of forgiveness; nobody else should pick it up.” I prepared for the procession.

Dropping the cross on the ground is the most effective thing one could do to move these people. Antonio was confused; everyone came closer to him begging him and asking him to pick the cross up; so much so, that he could not resist any longer and took the cross and kissed it and brought it to me. I asked whether he sincerely forgave, and he said, “Yes.” I asked him to kiss the cross again and I blessed him. Antonio very happily took the banner of the Sacred Heart, which during the forgiveness ritual he had given to someone else, and thus the procession started with such solemnity, that maybe nothing similar had ever been seen in Gomshiqe.

Father Domenico Pasi S.J.

Lettera Edificante della Provincia Veneta della Compagnia di Gesù; Serie V, pp. 91-93.

In: Giuseppe Valentini (ed.), La Legge delle Montagne Albanesi nelle relazioni della missione volante. 1880-1932, Firenze: Leo. S. Olschki Editore, 1969, pp. 77-79.