Professional Life

[Cut from the video interview: the interviewer asks the speaker about his professional life.]

Shaqir Hoti: In the 60’s it was like something had changed…earlier during our youth, we were a bit more ahead, but not that much more ahead. We finished high school and now, to be honest, I had a moral obligation to return to my village, to offer some sort of contribution there. Not because I got the grant, but because I wanted to work for a while there, especially to try to enliven it culturally and work with children because, to be honest with you, the first grade of the village where I was, in Damian, that always remained in my memory. And now I started working.

So I returned to my village in Rugova, of course there my profession was music, musical subjects. I took the subject of music, but because not a lot of time was reserved to musical education, I was teaching fewer classes. To fill in my time, I was teaching a skill-based subject or handiwork or something else like this. However, because of the lack of teachers there was always a class without a teacher, and I always preferred the second graders. Because at that time there was no longer the system of hiring one teacher for first to the fourth grades. But, to put it simply, as they say, it was a matter of chance (smiles): the class you got was the class you taught.

I always got the second grade. I studied the program well, and I worked to be successful with those children, and it really went well. With music only, as far as music class was concerned, I was very, very easy with those children because we didn’t have any instruments. I mean, an instrument that could be tuned, for example, if I were to have a piano, a pianino, something…but there was simply nothing, apart from my professional flute. However, a flute like a flute has a sound, it’s heard. But when two senses interact, meaning you hear the note and you see it as you hit the key, it’s a bit easier to grasp. So with music I wasn’t very happy, even though I’d managed to read notes very well. Meaning I was very good in solfeggio.

Then the school gradually started getting equipment, to buy the instruments slowly. I remember the first instrument well, it was a mandolin, there was a special excitement for that instrument. Gradually one more, and one more, then there were three or four mandolins, later on a violin, prim, bas prim.[1] Later on there was an accordion, it was the best when the accordion came because now I was much more able to develop the course. But with the kind of instruments I had there, I checked out the teachers a bit, a bit someone else, and we created a small group like this.

Back then there were performances, public appearances. I’d get the students ready, sometimes with individual songs, sometimes choral, for small choirs, not big ones. And to be honest, cultural life was positively enlivened there. We’d often hold performances in the village, but also around the village. So, the instruments that were brought to me in the school, without ever having played them, I only needed a short amount of time to practice the sounds and I very quickly mastered each of those mandolins, prim, bas prim, the violin. Of course the violin, I played it very beautifully, but I’m not a violinist. Because a violinist needs…there are certain positions, of course I only played the first position there, for the purpose of supporting our [albanian tune] melodic line.

So, life started now, to be honest, just the most important part in all my life. So, it was a youthful life and of all the times of my life, it was the best. Because I organized, we organized different parties, different excursions to cities, to villages, and elsewhere. We were, in short, very free, very…That time of my life in the village lasted seven years. It will always be one of the happiest times of my life. We were really very good friends and we organized these parties, these concerts. That was our life in the village.

Yes, but later on around ’63 or ’64…no it was ‘61, Lorenc Antoni came with…I think it was the ethnographer or ethnomusicologist Nikola Hercigonja from Zagreb. He was a researcher, he came to me in Rugova, to the village. I mean, it was the first year I was teaching. And he said, “Take the instruments you have and you’ll play a bit and Nikola Hercigonja will listen.” “Good.” I took them and played all of them. He was simply amazed by these instruments, with that request and he addressed Lorenc right away and said, “So, here you have something a bit more valuable than gold. He simply needs to be used and worked, to get the best out of him. This talent absolutely needs to be used.” Then it was his responsibility, he put it upon himself to also research singers in Gjakova and Peja…and he asked me to accompany him the entire time. “And you must take an instrument with you.” “Why, which?” “Only the kaval interests me!” And then I took it [the kaval], we went and would stay with different singers, Mazllum Mizini and all the Gjakovars and in Peja. And we returned, we slept at the Hotel Pashtrik in Gjakova.

And now there, in the bedroom, “Come,” he said, “take the kaval for a little bit and play some melodies.” He simply said, “I hear a very noble sound here. But I hear a sound that’s behind, behind there is the real soul of the instrument. Because of this, please take it with you.” So, I really left a good impression there.

And so later on, Lorenc came to Rugova several times and said, “You absolutely have to go to Pristina because we don’t have a flutist in the traditional orchestra.” [He came] once, twice or three times. I said, “I think I hear the flute in your orchestra.” He said, “Yes, it’s the flute, but that flute only knows the scores.” He told me, he said, “The flutist is not of our nationality, there’s no soul. The instrument is there, but the instrument has no soul. Since you know traditional songs, original songs, you absolutely must move to Pristina.” But I was in the midst of a big dilemma: to go to Pristina, to leave, to leave my birthplace, to leave the children I’d become very close to, seven years aren’t few. I had a big dilemma.

Later on, Esat Muçolli, who directed the orchestra at the time, visited quite often. He was also a former classmate, we had always been good friends and he said, “You absolutely must come. We absolutely need you to give color to the orchestra, we’re missing you.” “It’s done, we have a composer,” that’s how he said it. “You come for two to three years. If you don’t like it, go back.” And to be honest, “Good,” is what I said. I agreed, I gave my word. “In September we start working,” because they also had the summer, the whole summer, August off, “In September we start working, we have to start together.” “Good.”

I came to Pristina, the formalities of the recruitment were complete, the hiring. I was accepted and it was a permanent decision, it was called a permanent decision at the time, we had a year-long contracts, but they were permanent. And now we began to work with the orchestra. My mind was always with the children and my friends and so on. However, the time gradually passed and I kind of adapted to the environment here, I made good friends here as well, from the school but also new ones I made here.

I gradually acclimatized, or how do they say…there’s a folktale about this, it really plays a role – a villager with a horse and wood go to Prizren, to sell…there was a baker, bakers bought the wood. And when the horse sees the fountain flowing, runs to it to drink water, the villager doesn’t let it. There were usually silversmiths around, and they begged him, “Let the horse drink water.” “No,” he said, “because if he drinks this water, he won’t come back with me to the village” (laughs). And I came here to Pristina, I stayed as long as I stayed, I adapted, I came for one year, two, maximum three, but I stayed the whole time because I really found a place in the orchestra…a really suitable job.

I had significantly fewer obligations compared to what I did in the village, because in the village my obligations were more like a school teacher’s. I was always the deputy principal. While I lived in Rugova, I was the deputy principal for seven years. There, we had so many required school activities, only we know, we had to work on them at night as well. We were busy and obliged to work with the Youth League, with the Party League, with the Socialist League. There, we never had a break, except those nights when we organized parties.

Whereas here, I found something completely…a job that doesn’t compare to that. I only had obligations to my instrument. There wasn’t a Youth League, or a Socialist one, nothing. To be honest, I started working here in the orchestra as a flutist, I settled well from the beginning. Unfortunately, I complain a lot that there wasn’t a good instrument at the time. You found here a very dilapidated orchestra. I played, but I played with difficulty. A good instrument doesn’t need to have its keys well tightened, they’re lightly touched, but I was obliged to push them and to draw out a sound (laughs). So I always feel bad when I hear the Baresha [song that we recorded. I had a very worn out flute, and it was difficult to draw out sound. Even today when I hear Nexhmije[2] singing Baresha[3] [The Shepherdess] I’m bothered by the flute, because I didn’t have a better flute at the time!

I mean, the first year was excellent, the Akordet [Chord of Kosovo] festivals started, I participated in them also as a…I was busier in the orchestra, but I also participated in compositions. I competed in them with Adem Ejupi, with Shahindere Bërlajolli, an ensemble that I created here called Azem Bejta. With that ensemble I even won first place in 1972 with the lyrics of…the lyrics of our well know poet Rexhep Hoxha, Ah Hyrije [Oh Hyrije], it was a very beautiful text. And the members of the ensemble sang it, the interpretation was really excellent, I won first place. So, I only won the Golden Ocarina in 1972.

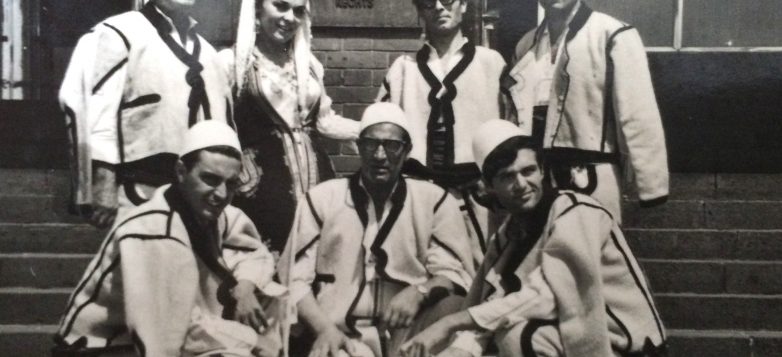

I was talking about Nexhmije and Baresha, I’ll come back to this. In 1969 it so happened, we won first prize for all [Yugoslavia]…it was called a Federation then. And now we represented Yugoslavia in an international festival in West Berlin. And I got on a plane for the first time, the plane landed in East Berlin, there they took us to the wall, the famous wall that divided Berlin, with three wagon-like taxis. A German driver, he told us, we didn’t know the language but we understood, he said, “Around boom, boom, mines. There are mines all around,” and we saw the very high barbed wire. And as we approached the border, we got out, we took our instruments. We walked past the wall, the Berlin Wall, it was a kind of labyrinth…you could not walk straight but it was a zigzag, to get to West Berlin. That zigzagging corridor wasn’t even very wide, it fit a person with two bags, more…And when we came out there, there was a big difference between the buildings, the parks, so much that it can’t be described. It was simply paradise there. Over there [East Berlin] you could see dark houses, you could see the poverty, everything – darkness and light over there, I don’t know how to describe the huge difference (smiles).

Anyway, we went there, after a two-day break, to the general rehearsal. When we went to the general rehearsal we left the rehearsal really disappointed because the orchestras of the other countries were very big orchestras, symphonic orchestras, choirs with 50 to 60 people, meaning a complete orchestra, violas and all. We only had six members in the orchestra, only six people, Nexhmije was the seventh. I mean we filled the stage with seven people, whereas they had over a hundred. And we were disappointed, what could we do, what should we do now, how can we compete. It wasn’t really comprehensible, but the time came.

A presenter, a beauty whom we had never seen anywhere else…she came to us time after time because she made mistakes with Nexhmije’s name. She said {imitates the presenter} “Nexh…Nexhm…Nexhmije, Nexhmije Pagarusha!” “No, not Nemxhije, but Nexhmije,” [we said] a few times until we taught her. We finally taught her, “Nexhmije.” When she went on stage she got it wrong again, she announced her, “Nemxhije.” Anyway, finally we were up, the first song was Bijnë tup…[The Drums Beat]. Nexhmije sang three songs in the festival, I accompanied the first song, Bijnë tupanat n’katër anët [The Drums Beat on All Four Sides] with a çiftelia.[4] There was great interest in the çiftelia. The second song was, Sytë për ty i kam të njomë [Because of You My Eyes Are Wet]. Both songs were composed by Isak Muçolli. I accompanied again Sytë për ty i kam të njomë with the çiftelia, there we were well received by the audience, we had something. But regardless, when we compared ourselves to those big orchestras…And the last one was Baresha.

With Baresha we just heard applause, we never heard a clapping that lasted that long in our lives, it became frenetic. But, we got off the stage, Nexhmije had to go out and take a bow and we went to the hotel. We didn’t know what happened. We knew we were successful, but not that much, no one officially told us anything. The Yugoslav Consulate in Germany came the next day. They came to congratulate us, to congratulate us, eh now…I mean, we won first prize there, we had great success.

We went there by plane, we returned by train, to be honest we came back more serbez,[5] a bit proud. [I imagined] we’ll go to Pristina, they’ll ask us about our success, the newspapers will write about it. There was the Rilindja newspaper back then, another newspaper…We came back, a week passed, then two weeks, then a month and ten months and now it’s been almost 50 years, it was ‘69 and no one wrote a single word about that event. And this is our worst fault. Our achievement should have been more openly recognized. It was really more our success than a success that belonged to Yugoslavia because we went in national costume, Nexhmije was also in national costume, and all the songs were Albanian. I mean, that was a very bad thing that happened, luckily Nexhmije had the German newspaper, where it’s written, I think it’s two pages or three pages, the fourth I forgot and she looks beautiful in the photo. These were those moments.

Now, we fulfilled our obligation, apart from our obligations at the Radio’s studio, we were only obligated to folk songs. The older singers had been accepted to the radio, I mean back then there was a criterion. Whereas the new singers, they had to go to auditions. Auditions were organized once a week, new singers would come, they’d sing. The committee would get together and would evaluate them, well, they’d listen to the predispositions of that singer, what kind of intonation, what kind of diction, what kind of color the vocals have, what is their breathing like, these are all the elements that a singer has. So here there were evaluations, and only if a singer fulfilled all the conditions then that singer would come occasionally and record.

Apart from our obligations to record two songs twice a week, meaning four songs, we were also obliged to perform in concerts in Kosovo and outside of Kosovo and in other republics, but also in other countries. We had an especially great time in Western countries, and usually in those countries there were more Albanians because they started after the 70’s, the Albanians began going there to work. Then in those places…twice a year, once a year, usually during the holidays in November and May.

Of course, we also traveled through, and outside Europe. We also went to the U.S. twice, all of us. So there was all of that, those concerts, those simply, those [political] parades I will call them, they were all organized. We missed a little bit, not a lot, but we missed our freedom. We went as an orchestra, as singers, but we always had a written repertoire, stamped with three stamps and we couldn’t deviate from those songs. And if there were requests, because people were hungry for their homeland, there were some and many who had run away from here [Kosovo], they asked for a bigger program, for more songs. But, instead of singing another song we would repeat a line, or two or more because more was not allowed.

And another thing we felt was lacking, was that all the songs were “lale-lule”[6] songs as we say. Or all of the songs were more like love songs, and not poetic songs because they had a national character, heroic songs …no, no love songs. Sometimes, sometimes they’d let us have a song about some brave act against the Turks. That was allowed, whereas these others weren’t allowed. That was our biggest deficiency, it was this…we would go, but not willingly. This was the professional work that we started at the radio.

Kaltrina Krasniqi: When did you start going to Albania? What was your relationship with Albania?

Shaqir Hoti: Yes, yes.

Kaltrina Krasniqi: When did you start working together?

Shaqir Hoti: Well, as part of our job, we started and we worked until the violent measures began. We had there, in ‘71 it happened accidentally during a wedding, an Albanian person organized it, and invited us to Belgrade. There was a wedding, his daughter was getting married, the wedding was held at the Belgrade Hotel. And we went, we performed the entire night, it was a beautiful party. The next day, I mean we were all sleep-deprived, we were like, let’s have a bit of breakfast and go back to Pristina. And behind me I heard about three people speaking Albanian so beautifully, so fluently, it had been a long time since I heard something that beautiful. And I told my friends, “Oh brother, they’re talking in Albanian, I’ll say good morning to them.” “No, no because we don’t know…” “Whoever they are, I can’t stand it.” And I turned around and said “Men, good morning!” “Oh, good morning! Come, let’s sit together, let’s stay!” But now, we didn’t know who these men were. They came, they sat there, the first person introduced himself and said, “I’m the Ambassador…the Secretary of the Albanian Embassy, Hajrullah Kuploja,” and he gave me his name, uh yes. And the other and the other one were working at the Embassy.

It was…there was a very good festival in Albania called Dekada e Majit [The Decade of May]. It was close because we were always eager to visit Albania. And we said to the Secretary, “The festival is approaching, we would really like…is there a way for us to join the festival?” “But of course, it’s very, very possible. So one of you take your passports, not all of you, just one, I’ll give you a visa, now you’ll go.” And we sent a friend of ours to Belgrade…Zef Tupeci. Now the poor man is dead. He went and got the visas, he came back. He came back, he gave them to us, without us asking anyone. And now what do we do? We have the visas, but we don’t have permission. And we went to the general director Kemal Deva, we went to the office, when he saw us even he was surprised, “Ha, what happened? Why is the whole orchestra here?” And we told him this, and this, “We started this almost accidentally, but it really happened. We have the visas, we don’t have permission, what do we do?” First we went to the radio to get leave from work. “You,” he said, “absolutely have to go! You have permission from the radio station, I’ll try to get permission everywhere it’s required, I’ll take care of it, you have to go.”

And they really did let us, we went there, but we only got permission to stay a week at the festival, it lasted two weeks. When the week ended, we got our bags ready to return, a festival organizer named Lirije Çeli called us. “Where are you going?” “We’re going because this is all the time for which we have permission.” At that moment our general director called. “You have permission to stay for the other week as well. Until the festival is over you don’t move.”

It was a reception that was, it was indescribable, a very, very warm reception for that time. But understandably the times were like that, we couldn’t go anywhere without a minder. And that was, we noticed this, we saw the good and the bad. It seemed good because at that time, there wasn’t a single person without work, but it started looking bad when we went to stores. You could see, there were no goods, there weren’t…and then the people were dressed very poorly. And, even the tan on their faces was paler than ours. And then when we came back and people asked us, the ones close to us, and we told them honestly, we had a kind of dilemma whether to tell them honestly what we saw, that there was good and bad. They would have called us spies a little bit (laughs). So we were in a bad situation. Memories of life sometimes come out (laughs).

Kaltrina Krasniqi: You worked at the radio until when?

Shaqir Hoti: I started working at the radio when I came. I came, as I said in 1967 until the violent measures began, meaning until ‘89, understandably that moment, the entire world also saw how they invaded. From that day on we left the radio and nobody asked about it. Later, after the war, Radio Kosovo was created, but many of us did not join this Radio. Almost all of us actually did not join. And everybody took care of themselves as best they could, some are…some simply remained at home.

Our activities, you know, they were always connected to our work, I mean, not to our other activities with the orchestra. But from ‘72 on, it seemed like we were a bit freer. It seemed like something changed in the repertoire of the songs, we were in a better position. Even though we went abroad to those organized concerts, with those real tours, we were a bit better. But, in 1981, that’s when everything began happening, such as censorship, but it was more than censorship. A song couldn’t be recorded because of one single word. Especially in the 80’s, like from ‘81 onwards censorship began, a song could be refused because of a single word. It became harder and harder as a radio orchestra to secure basic work conditions. And, to be honest, this was the norm of work that we had, because it would either be refused for a single word, or, if it was approved by chance, it could only be written on paper, but the second time it wouldn’t…it wouldn’t get through. And we had a sort of metal cabinet, and the songs were put in that cabinet that was called “Embargo.”

It happened to me, when I wrote a song and it was performed only once in its entirety, Malësore,[7] which was sung by Adem Ejupi. “Oh my mountain girl, oh Albanian, shining like a fiery star from the mountain,” these were the first words. And now it was taken to the “Embargo” cabinet and in general I was asked, “Whom are you singing to? What does that mountain girl mean, a brave Albanian from…? You wanted to hide something!” “Oh no bre,[8] that text isn’t mine at all. I only did the melody,” but only because of that I had a big problem. Meaning, the worst was always assumed. Every day, every demonstration, it got worse not only here for us, but the situation everywhere. Things continued to get worse and worse until the violent measures began, the violent measures.

Our orchestra was on holiday, annual holiday. Many times, almost every year, we had an annual holiday of two months. One month leave was given to us because we always had long shifts, whereas we earned another month with the additional work we did, with festivals, with concerts, with those things. That’s why I said we weren’t paid well, but we got holidays. And we were on holiday when the violent measures were introduced, after the entire world saw that violence, that…And from then until now, all of us and the orchestra, and the others, however, they were able to take care of themselves, some of them went abroad, some remained at home, some… To be honest, I was engaged in other activities that I always kept close to my heart. I never stopped regardless of all the other obligations that I had. Even in education, even here, here in the radio, I never deviated from traditional instruments.

I earlier worked a little bit on every traditional instrument that fell into my hands, maybe I intervened in regards to its tuning, a note I didn’t exactly like, I either had to put it down or work on it in order to get the sound that I needed. I worked like this, I worked alone on some simple things, some pipes, made some repairs that [the instrument] needed in that moment, and I dealt with this stuff…But I always intended to study these instruments a bit when I retired. But I always intended to advance this instrument, to preserve it in three ways: to interpret it in the best way possible, so that it can be accessible to every ear; to work alone and through my work to research which wood is best, which metal, what kind of plastic, I mean there are much more possibilities for these developments; and third, the third is I wanted to write about each instrument individually.

I wrote about each and every instrument, especially traditional instruments, the possibilities of working with it, I mean the technology of working with it… the skill of playing it is, very honestly, here one needs to be careful, especially when playing, because instruments have their own sound. I’ll take the flute as an example that has different names: flute, whistle, nightingale and others, there’s the fancik,[9] it has many different names in different parts. It has its own sound, and everyone can play it, you put it to your mouth and blow. While our instrument really must be much older, even though its origin is lost somewhere in the darkness of antiquity, we can’t know, but it is believed according to all musicologists, it is believed that it’s very old, fyelli i shokës.[10] It doesn’t have a voice that needs to be formed through the musician’s lips. So, one needs to be careful there, to read it well. How can it be read, I believe anyone who takes it in his hands, very quickly develops embouchure with it. Fyelli i shokës is also unique because you can also hear breath in its sound. The breath really helps one understand the instrument, that instrument is very noble. Behind this instrument you really see a person, a human, so it’s the only instrument [that can achieve that.]

And, first of all I started interpreting every genre. I never ignored any of them or said, “No, I don’t want to go here,” but I explored every genre, just so that the traditional instrument would be heard. When it started later on, meaning after the war, when rap also started, rock was introduced widely as well, it was like I wanted to avoid that genre and I was with my professor who I was really very close with, we were with Engjëll Berisha. And I said, “It’s best not to explore this genre, what do you think?” “No, on the contrary, I order you as your professor, and as the friend of yours I’ve become. You have to go everywhere. Let that sound be heard by someone’s ear, at some point maybe someone who hears it will like it, because that instrument becomes closer to them.” And in this way I didn’t ignore any genre of songs. I always played for films, meaning the film Kukumi […] Rojet e Mjegullës […] and others. In the theater, in the theater, I also participated in serious music, meaning I performed very well in every genre and was well liked. To this day, there have been no complaints about this, and I am personally satisfied.

Then I started working with each instrument by myself. During my work I also researched, as I said earlier, the timber, the development of that instrument as well, because many of them, for example the bishnica,[11] or the gajde,[12] which are well known around the entire world, today the bishnica has many names. Every region gives it its own name, bishnicë, mishnicë, meshnicë, tërquk, there are kacek and others. I mean the gajde is well known throughout the world. It’s very well liked; it has a very nasal sound, but a very pleasant one. However, its musical scale is very limited because it only has five notes…six notes. Five openings release six notes. Whatever number of openings a musical instrument has, it always has an additional sound.

And after the war, I worked with the ensemble that I had. I formed “Azem Bejta” when I came to Pristina. At that time I put out a lot of records with them, gramophone records. I did many recordings in Radio Pristina that the music library of Radio Kosovo now houses, they have them, they have them in its music library. I took them now, I re-activated them and after the war we performed occasionally, we rehearsed, we practiced. We released an album, the other one is ready. Maybe we could also record that somewhere, [the money doesn’t fall from the sky] the sky is mean {rubs fingers} (smiles). It still needs…the studio time needs to be paid for, but we’ll find a donor. I’m also close to finishing a second album with the ensemble. Even though they’re old, they’ve returned to the music beautifully, because as we know everything goes with…youth has a different kind of élan, a different force…they’re different. But in rehearsals we gave it to the maximum, at least to give…to say “Good, good,” somehow you want to do justice to the song, good, they’re good, they’ve practiced some songs.

[1]Prim is an instrument similar to çiftelia, which is a two-string traditional Albanian instrument with a long neck. Prim is also developed to be tuned for bass sounds, as such it is called bas prim.

[2] Nexhmije Pagarusha (1933-) is one of Kosovo’s first classically trained singers. Her repertoire covers classical Albanian music and folk songs. She is known as the “Nightingale of Kosovo.”

[3] Baresha or The Shepherdess is one of Pagarusha’s most celebrated songs. It describes the life of a mountain shepherdess. The song was composed by her husband, Rexho Mulliqi. The lyrics were written by author Rifat Kukaj.

[4] Two-string traditional Albanian instrument with a long neck.

[5] Turkish term for relaxed.

[6] Albanian expression for kitsch.

[7] Literally, a mountain girl, but it can also be used to refer to girls from Malësia. Malësi e Madhe, (literally Great Highlands) is a region largely inhabited by Albanian speaking people, which lies to the East of Podgorica in modern day Montenegro, along the Lake of Shkodra in modern day Albania, next to Kosovo.

[8] Colloquial: used to emphasize the sentence, it expresses strong emotion. More adds emphasis, like bre, similar to the English bro, brother.

[9] Another Albanian local name for the flute.

[10] Shokë is a traditional Albanian male belt, made of woolen material, knitted using a loom. Fyelli i shokës, refers to a smaller flute that could comfortably fit in the belt. Something like a pocket flute.

[11] A traditional woodwind instrument.

[12] A traditional bagpipe, found throughout the Balkans and Southeastern Europe.